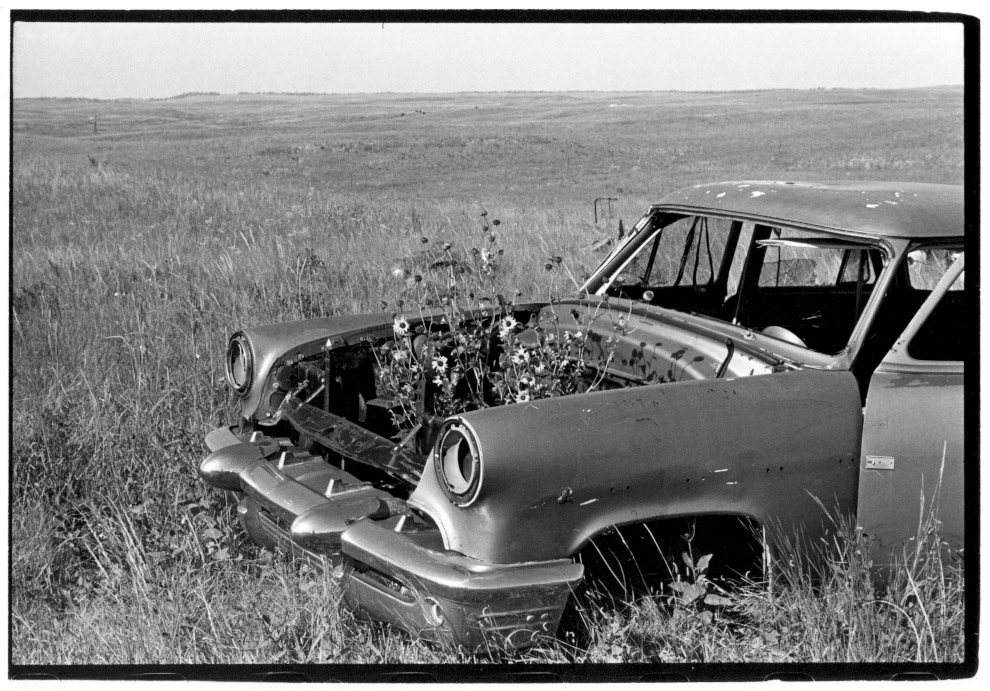

A photograph is a vestige of a face, a face in transit. Photography has something to do with death. It’s a trace. – Henri Cartier-Bresson

In the forty years since Michael Lesy published his classic book Wisconsin Death Trip, there has been increasing interest in publishing collections of vernacular photographs. The challenge these publications face is sweeping away the funereal haze so that viewers can actually engage with the photographs.

What made Wisconsin Death Trip groundbreaking was the multiple ways Lesy tackled this issue. Along with the unconventional title, Lesy employed an unusual design approach that, while dated now, still successfully keeps readers on their toes. And through the incorporation of hundreds of local news stories, Lesy helped readers imagine the life and times of the people in the pictures. Lastly there was Lesy’s own text. “The pictures you’re about to see are of people who were once actually alive,” he writes in the first sentence of the book.

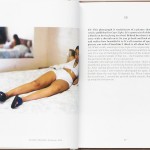

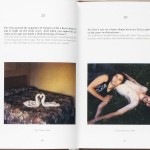

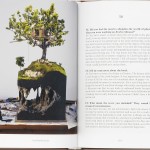

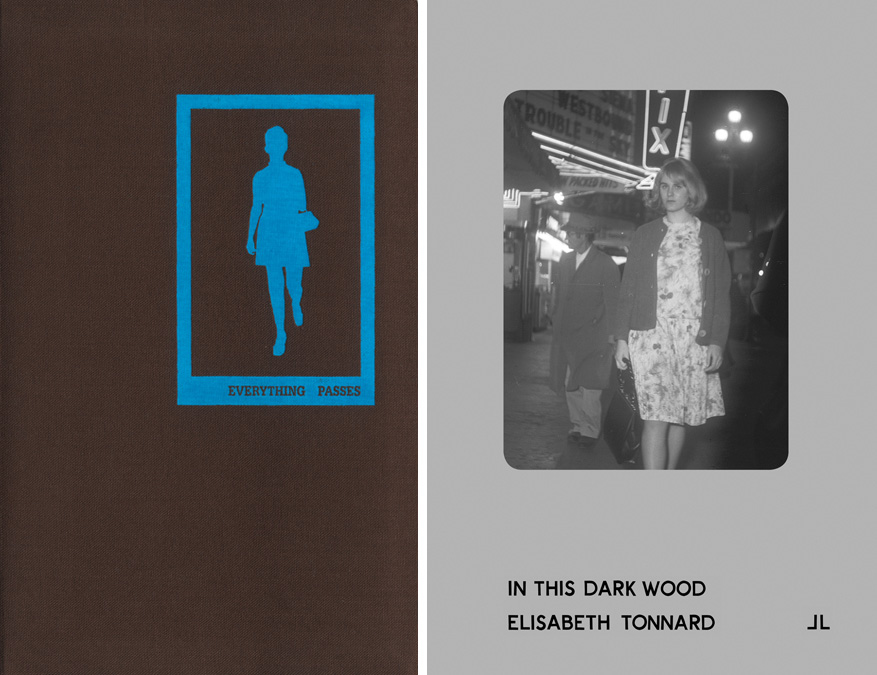

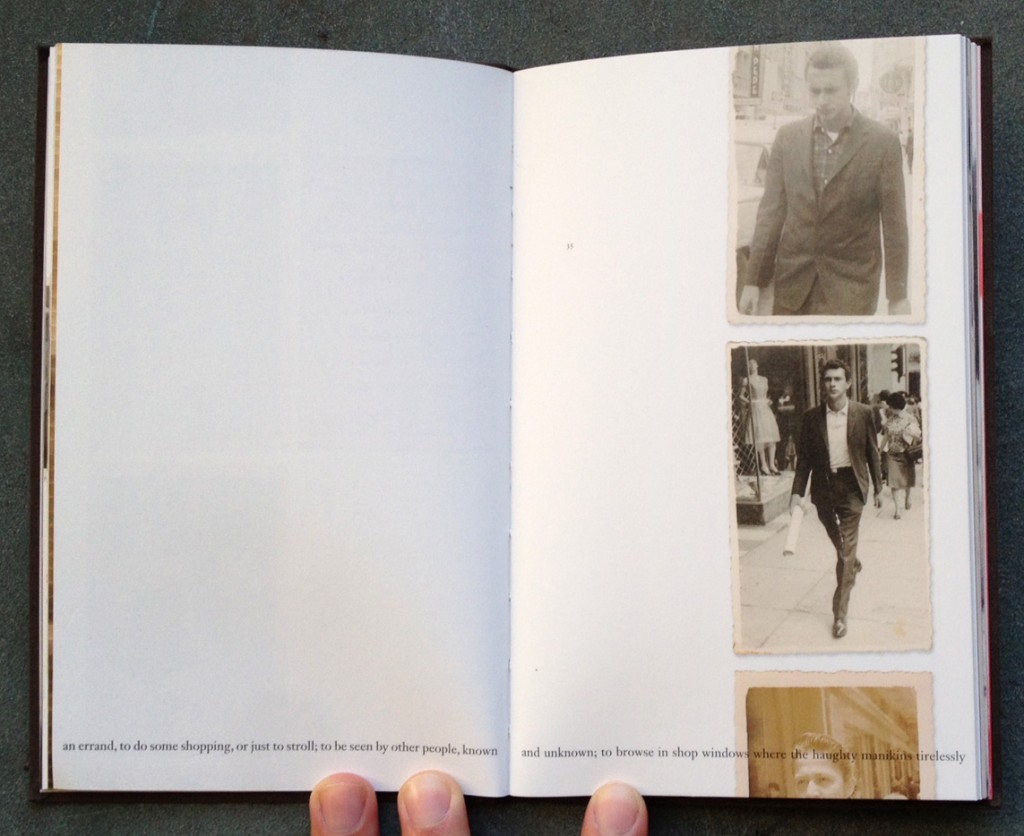

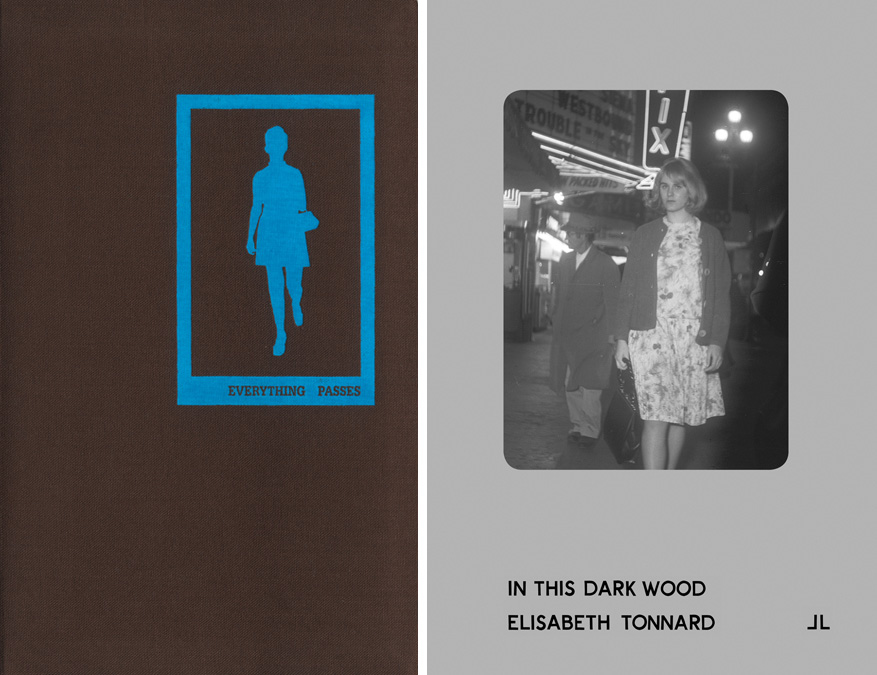

One of my favorite recent books of vernacular photographs is Elisabeth Tonnard’s In this Dark Wood (the book was originally self-published in 2008 but is now being reissued by J&L). At the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, Tonnard worked with the Fox Movie Flash collection; approximately one million photographs on 35mm half frames of pedestrians in San Francisco. Drawn to the nocturnal images of people walking alone, Tonnard was reminded of the first lines of Dante’s Inferno:

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita,

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura,

ché la diritta via era smarrita.

Tonnard ended up pairing ninety of these photographs with different English translations of those first lines. Compared to Lesy, Tonnard’s approach is minimalistic. But the effect lyrically brings the nightwalkers to life.

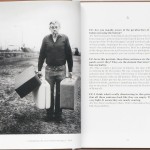

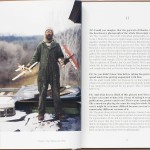

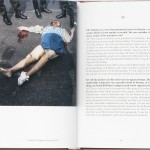

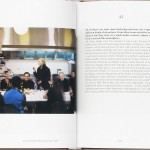

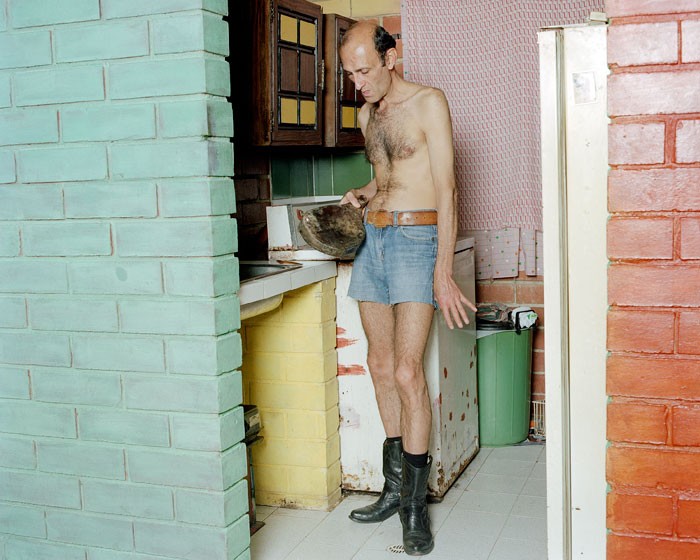

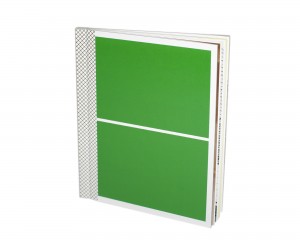

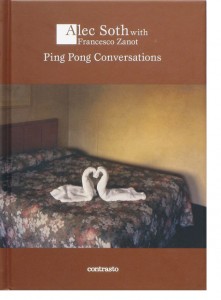

One of the joys of viewing vernacular photography is finding images connected to one’s own passions. As a big fan of table tennis, for example, I had a blast collecting the pictures for our recent book Ping Pong. After a recent trip to Bogotá, another emerging interest of mine is Colombian photography. So I was thrilled to discover Everything Passes. As with In A Dark Wood, the images are of pedestrians made by street photographers (fotocineros) on half-frame film. But in this case, all of the images were made along a legendary thoroughfare in Medellín called Calle Junín.

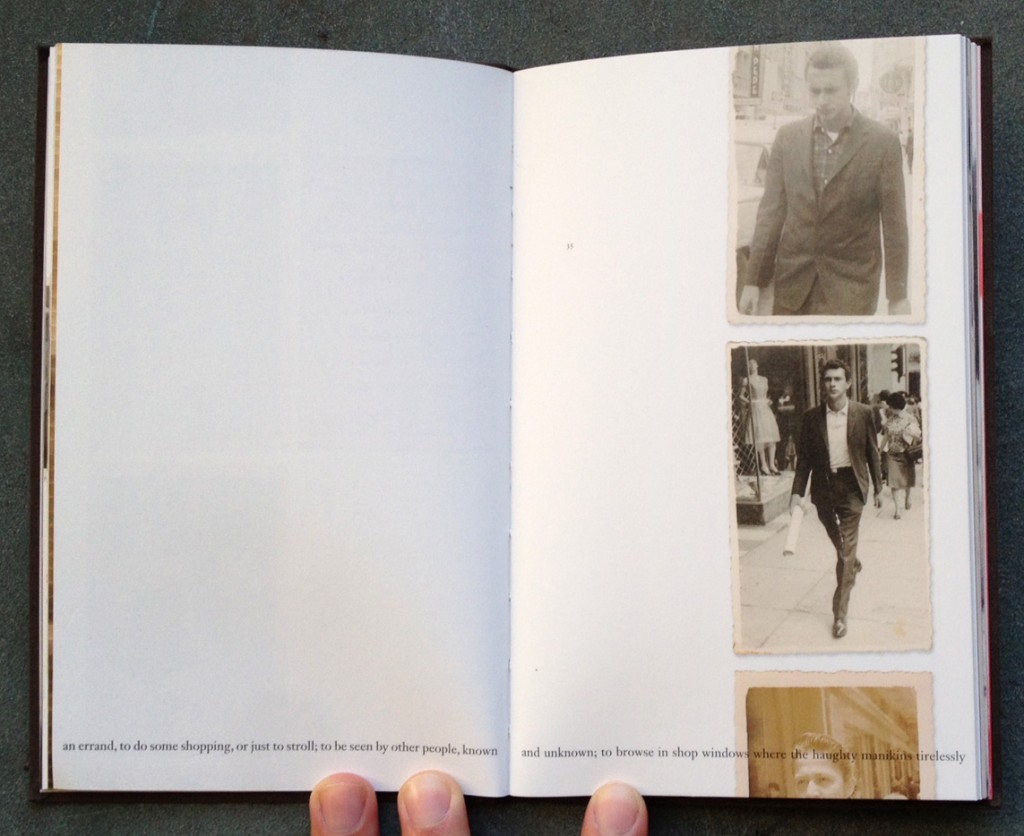

Everything Passes is a modest book. Nevertheless, it doesn’t settle for simply reproducing nostalgic images. As with Wisconsin Death Trip, the publishers employ a cinematic approach to sequencing the images. And while the text by Alfonso Morales isn’t as conceptual as Lesy’s or Tonnard’s, it did help me enter the world of the photographs:

Strangers to the street, to the city and the time, we have no choice but to trace back the steps of the passerby portrayed to the very limits of our gaze. In order to understand the experiences they have accumulated, we need to follow them back to before the day and exact moment when they were chosen by the fotocinero to figure as the subject of an instant portrait…To go back as far as 1675, when the history of the Nueva Villa de la Candelaria de Medellín began…To return to a time when Calle de Junín was known as “slippery street” because of the number of people who slipped in the mud there during the rainy season…when it was still thought to be haunted by a night-walking ghost that threw pebbles at passerby…To return to the days when the places were built that would make the street a required destination: The Astor tea and pastry room (1930), founded by Swiss immigrants, the Versalles restaurant (1961) the first place to sell soft drinks in Medellín, the Teatro Junín (1924) since demolished to make room for the Coltejer skyscraper (1968), the Club Union, the favorite spot of the local paisa high society…

Perhaps then we would understand why the name of the street has been turned into a verb: juninear ‘to Junín,’ which means to go to the street to run an errand, to do some shopping, or just to stroll; to be seen by other people, known and unknown; to show off your clothes before the lens of a camera, which is really the threshold of another landscape, the gateway into a territory in which people are transformed into images and the images, freed of their weight, set out for unknown destinations…

Reading this text as it scrolls along the bottom of the page like subtitles in a foreign film, the photographs begin to change. While the clothes and hairdos will always evoke a quality of nostalgia – and thus of death – I’m reminded of the actual people that walked these streets – “the people who were once actually alive.”

I love making books, but I continually struggle with the issue of accessibility. For students and everyone else on a budget, my books are either too expensive or too hard to find. For awhile that problem was resolved with my exhibition catalog From Here To There, but now that book is out of print and escalating in price.

I love making books, but I continually struggle with the issue of accessibility. For students and everyone else on a budget, my books are either too expensive or too hard to find. For awhile that problem was resolved with my exhibition catalog From Here To There, but now that book is out of print and escalating in price.