A recent study suggests that “Facebook envy” affects one in three users of the site. Family happiness was noted as a particular source of grief and vacation photos the greatest cause of resentment.

I confess I felt similar pangs of envy while reading Tamara Shopsin’s memoir, MUMBAI NEW YORK SCRANTON. The book starts with Shopsin and her husband vacationing in India. It didn’t help that I read about their travels while on my own family vacation to Wisconsin Dells. While Shopsin and her husband visit neglected museums and hunt for arcane mementos, I was staying at Kalahari – the 2nd largest indoor waterpark resort in the country – with several thousand other miserable Midwestern families.

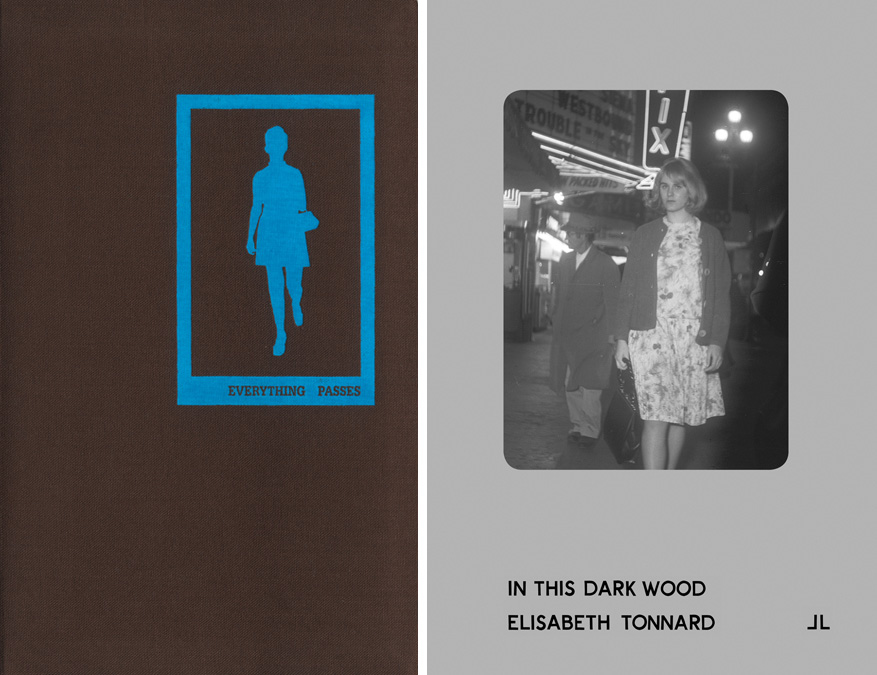

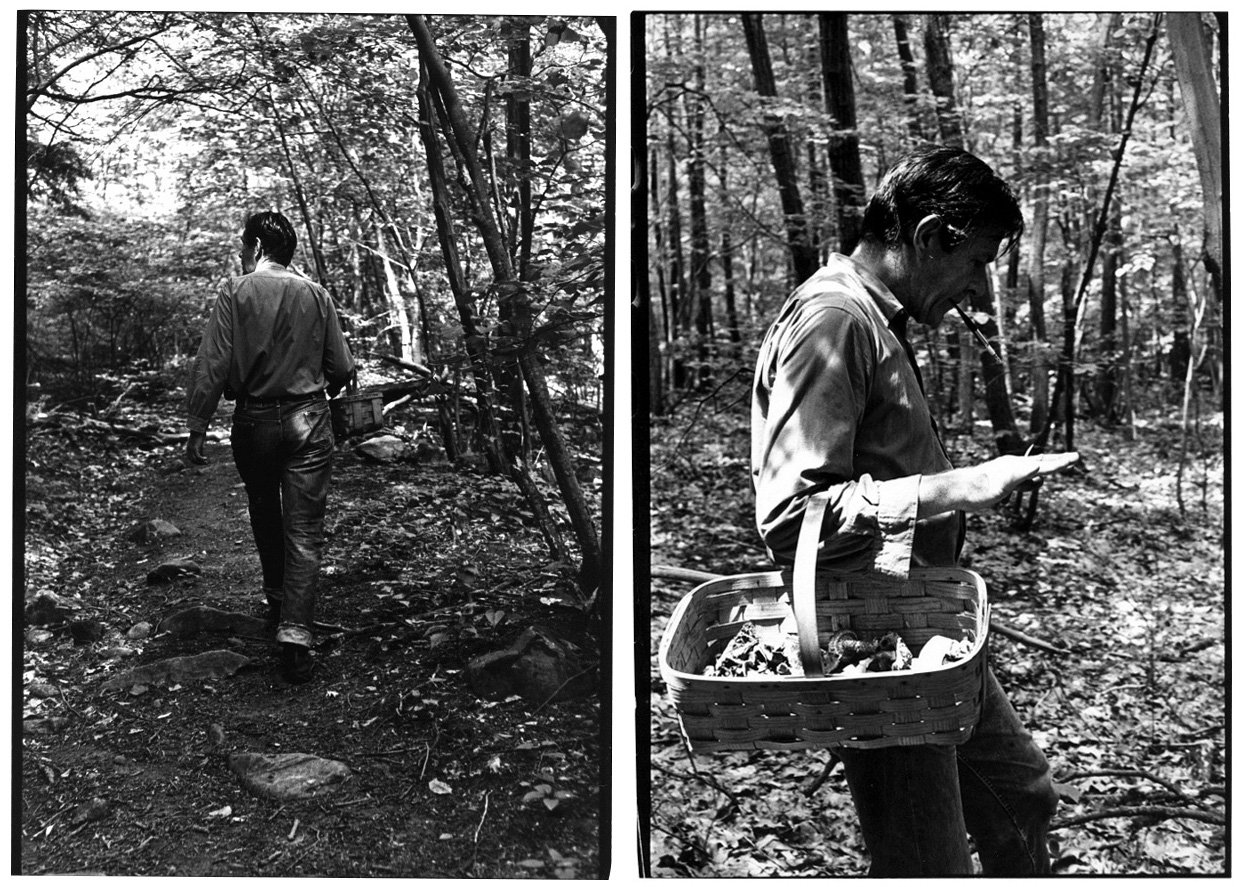

Nor did it help that Shopsin’s husband is Jason Fulford. Not only is Fulford one of my favorite photographers and publishers, he appears to be an unusually sweet husband. He calls Shopsin “beach ball,” sends her postcards while they are traveling together, and comforts her by resting his chin on her eye.

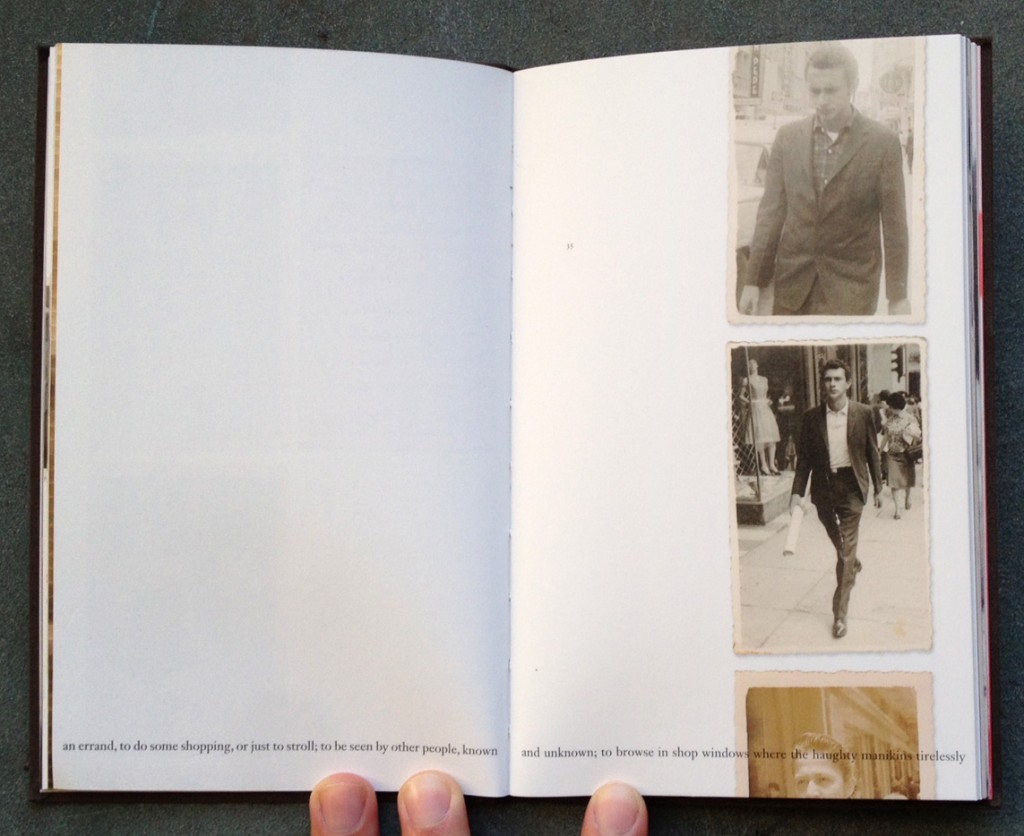

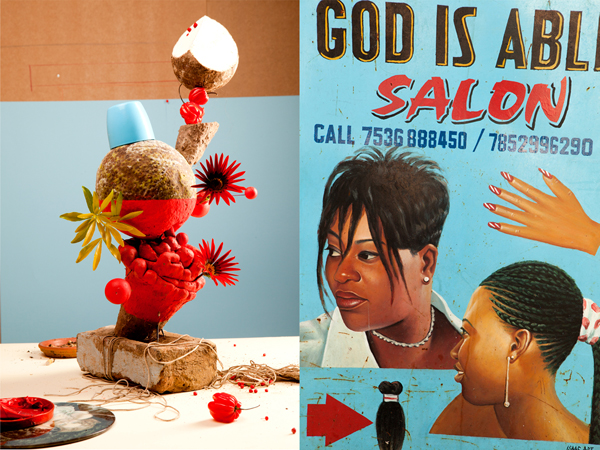

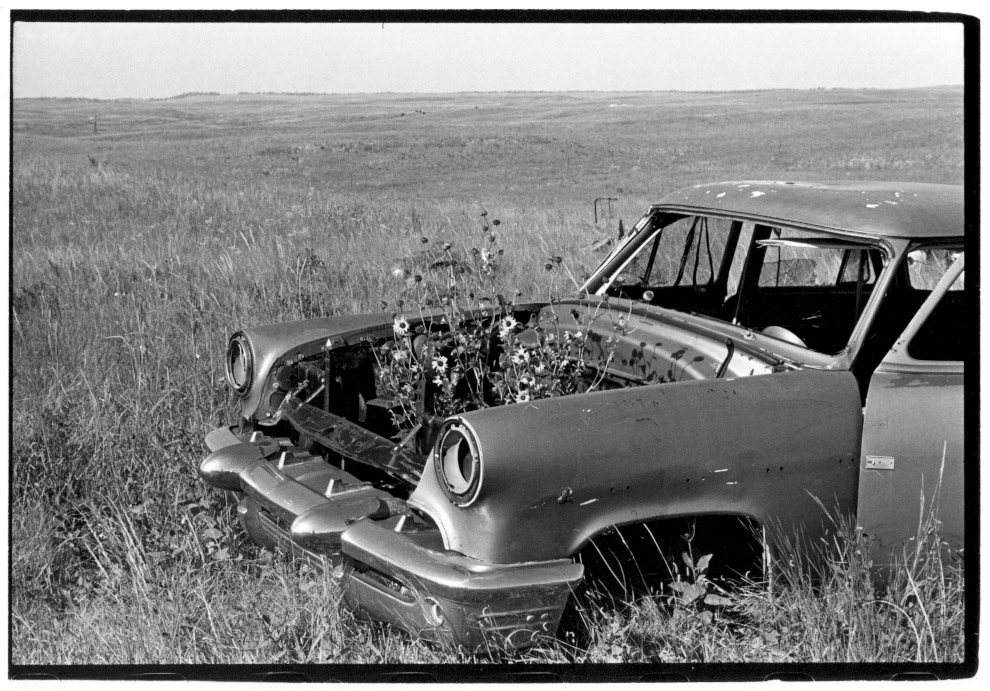

Like the most lyrical status updates you’ve ever seen, the couple’s photographs and illustrations sprinkled throughout the book are only more cause for envy. But even without the artwork, Shopsin and Fulford are able to make a trip to the grocery store charmingly romantic:

Jason pushes the cart. He calls it a “buggy.” This and calling any kind of soda “Coke” are all that’s left of his Southern accent

People study meditation for twenty years to clear their minds of worry and distraction. Jason and I go to Wegman’s.

The first stop is always produce. Jason gets the standards. Green beans, Fuji apples, baby carrots and so on. I find the curve-balls like fennel or beets. The fish department has misters in the cases. We hold hands and pick out a salmon fillet because it has omega-3. I remember we need peanut butter and am rewarded with a kiss. The ritual takes an hour, costs $125, and will feed us for a week.

Not only did reading this make me envious (why don’t I grocery shop with my wife, much less while holding her hand?), I felt guilty for feeling envious (why can’t I be more self-assured like Tamara and Jason?).

After drowning my self-pity in Amstel Light on the fake beach of Kalahari, I read on. It actually takes a long time for Shopsin to get to the “harrowing adventure” described on the book’s dust jacket. On his Facebook page, Shopsin’s friend John Hodgeman describes it this way:

There is a THING THAT HAPPENS in this book, and I knew what it was, and what a devastating surprise it was, and what happened after…

And when I finally did reach the moment where THE THING THAT HAPPENS started to happen, I audibly gasped in surprise, which I never usually do. I realized suddenly that every sentence led to this inevitable thing, and hinted at it, and I should have known all along.

I too was surprised by THE THING THAT HAPPENS. And it was fascinating to see the way it shaped my understanding of everything that preceded it. Suddenly, the stroll through the supermarket made sense. Shopsin was seeing the scene with the precision of an artist and the gratitude of a survivor. My envy vanished.

The morning after finishing MUMBAI NEW YORK SCRANTON, I discovered the omelet bar at the Kalahari’s breakfast buffet. I loaded up my bowl with onions, mushrooms and jalapeno peppers. When the omelet was done, I smothered it in Tabasco and Sriracha. I sat next to my wife and enjoyed every bite. I even considered posting a picture on Facebook.