#1) While browsing in a bookstore for this week’s popsicle, it occurred to me that the act of looking for a book is often as much of a learning experience as the book I eventually read.

#2) On a fruitless search for James Wood’s book, How Fiction Works, I stumbled upon Reality Hunger: A Manifesto by David Shields. Normally any self-proclaimed ‘manifesto’ written after 1960 is something I wouldn’t pick up, but then I got sucked in by the blurbs.

#3) I’ve just finished reading Reality Hunger and I’m lit up by it –astonished, intoxicated, ecstatic, overwhelmed…It really is an urgent book: a piece of art-making itself, a sublime, exciting, outrageous visionary volume. – Johnathan Lethem

#4) Opening the book, I noticed that rather than chapters, Reality Hunger is divided into 618 short sections. I read the first few.

#5) Number Three: An artistic movement, albeit an organic and as-yet-unstated one, is forming. What are its key components? A deliberate unartiness: “raw” material, seemingly unprocessed, unfiltered, uncensored, and unprofessional. (What, in the last half century, has been more influential than Abraham Zapruder’s Super-8 of the Kennedy assassination?) Randomness, openness to accident and serendipity, spontaneity; artistic risk, emotional urgency and intensity, reader/viewer participation; an overly literal tone, as if a reporter were viewing a strange culture; plasticity of form, pointillism; criticism as autobiography; self-reflexivity, self-ethnography, anthropological autobiography; a blurring (to the point of invisibility) of any distinction between fiction and nonfiction: the lure and blur of the real.

#6) I bought the book and devoured it as quickly as I could.

#7) Number Two-Hundred-Thirty-Nine: Living as we perforce do in a manufactured and artificial world, we yearn for the “real,” semblances of the real. We want to pose something nonfictional against all the fabrication–autobiographical frissons or framed or filmed or caught moments that, in their seeming unrehearsedness, possess at least the possibility of breaking through the clutter. More invention, more fabrication aren’t going to do this. I doubt very much that I’m the only person who’s finding it more and more difficult to want to read or write novels.

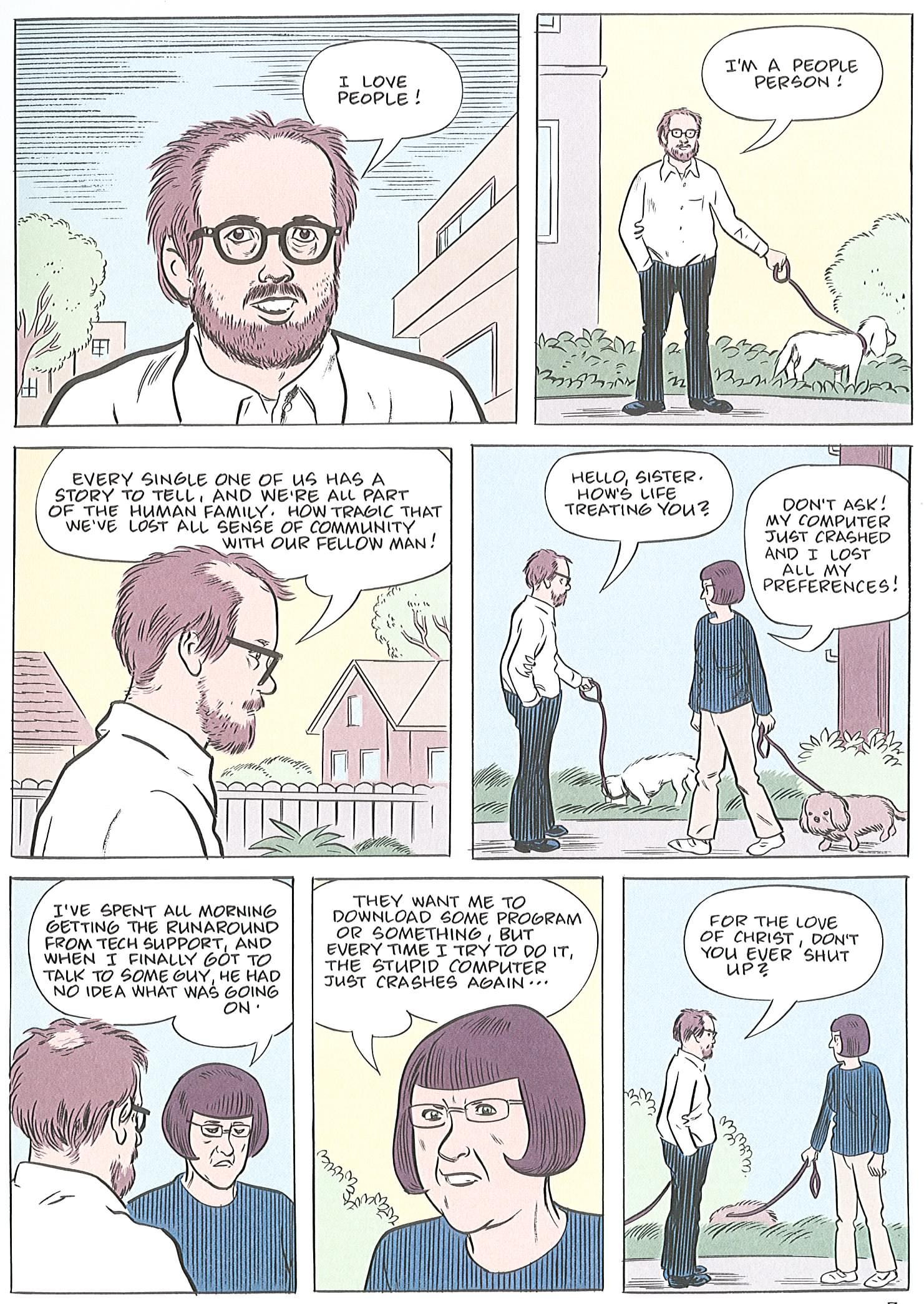

#8) A lot of what Shield’s talks about made me think about the work I’ve been doing the last few years. He made one remark that might just be the mission statement for my current project, The LBM Dispatch.

#9) Number Five-Hundred-Six (excerpt): Walt Whitman once said, “The true poem is the daily paper.” Not, though, the daily paper as it’s published: both straight-ahead journalism and airtight art are, to me, insufficient; I want instead something teetering excitedly in between.

#10) As much as I enjoyed the book, there was one thing that was nagging at me.

#11) Number Five-Hundred-Fifty-Three: Literary intensity is inseparable from self-indulgence and self-exposure.

#12) James Wood writes about Reality Hunger saying “He [Shields] rants a bit, apparently fearful that if he were quieter we would not believe in his sincerity; hungry for his own reality, certainly, he also mentions himself a great deal.”

#13) Throughout the book, Shields makes reference to Phillip Lopate’s introduction to The Art of the Personal Essay. I tracked down a copy and was struck by one section entitled ‘The Problem of Egotism.’ All personal essayists “have had to wrestle with the stench of the ego,” writes Lopate, “A person can write about himself from angles that are charmed, fond, delightfully nervy; alter the lens just a little and he crosses over into gloating, pettiness, defensiveness, score settling (which includes self-hate), or whining about his victimization.”

#14) As usual, when I read about literature, I think about photography. More often than not this gets me to thinking about Robert Frank. What makes The Americans so great, I think, is that it is the work of a profoundly introspective artist looking outward. The scales are balanced. While I love some of Frank’s later work, much of it looks like it was made by a sixteen year old emo kid drowning in introspection. I wish he’d spent more time after The Americans pushing back out into the world.

#15) My least favorite Popsicle reading thus far was The Unfortunates by B.S. Johnson. I wrote this in my post: “Johnson is adamant that art speak the truth. Though defining himself as a novelist, Johnson was opposed to fiction. “Telling stories is telling lies,” he famously wrote, “The two terms, truth and fiction, are opposites.” Consequently, the pamphlets in The Unfortunates read less like a novel than like artful Facebook status updates from a depressed, self-absorbed acquaintance.”

#16) One of the favorite things I’ve read all year was Jess Walter’s non-fiction essay that closes his book of short stories, We Live in Water. Entitled ‘Statistical Abstract for My Home of Spokane, Washington’ the piece consists of fifty numbered sections. Many of these sections simply consist of factual information about Spokane.

#17) Number Six: On any given day in Spokane, Washington, there are more adult men per capita riding children’s BMX bikes than in any other city in the world.

#18) Intermixed with this data are personal stories and observations by Walter about his hometown.

#19) Number Twenty-Seven: I remember back when I was a newspaper reporter, I covered a hearing filled with South Hill homeowners, men and women from old-money Spokane, vociferously complaining about a group home going into their neighborhood. They were worried about falling property values, rising crime, and “undesirables.” An activist I spoke to called these people NIMBYs. It was the first time I’d heard the term. I thought he meant NAMBLA—the North American Man/Boy Love Association. That seemed a little harsh to me.

#20) I love that Walter balances his own experience with hard data about his hometown. Instead of being lost in the double mirror of solipsism, Walter keeps looking out the window.

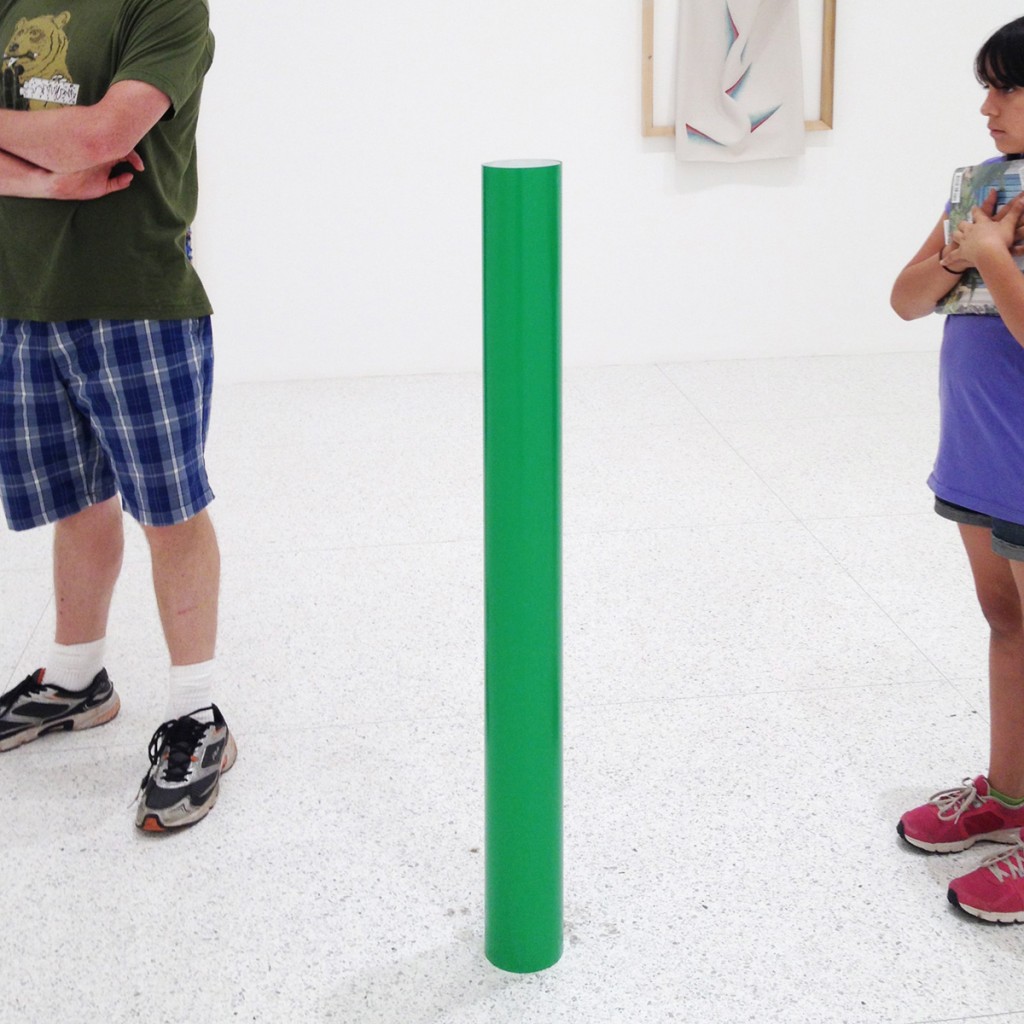

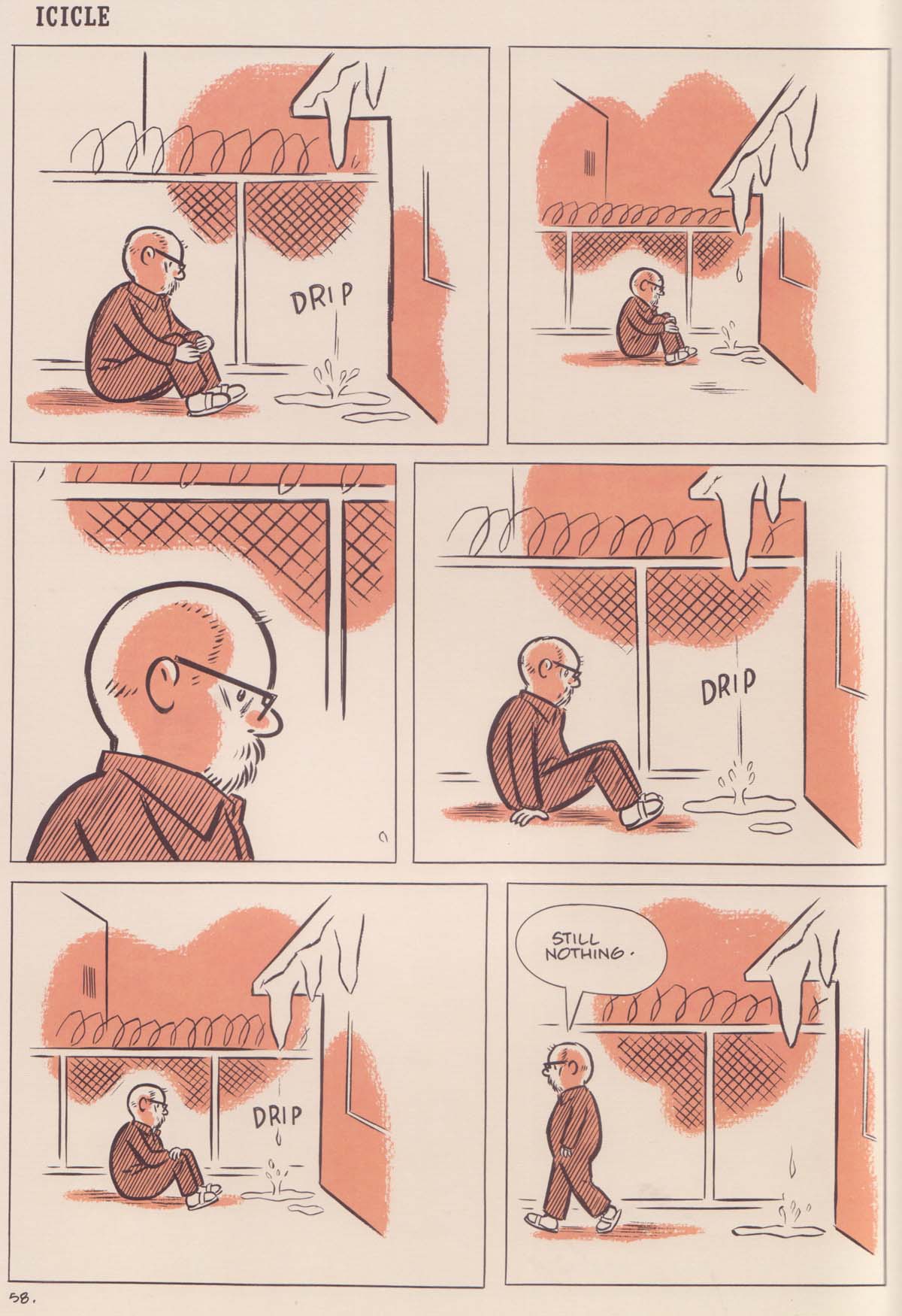

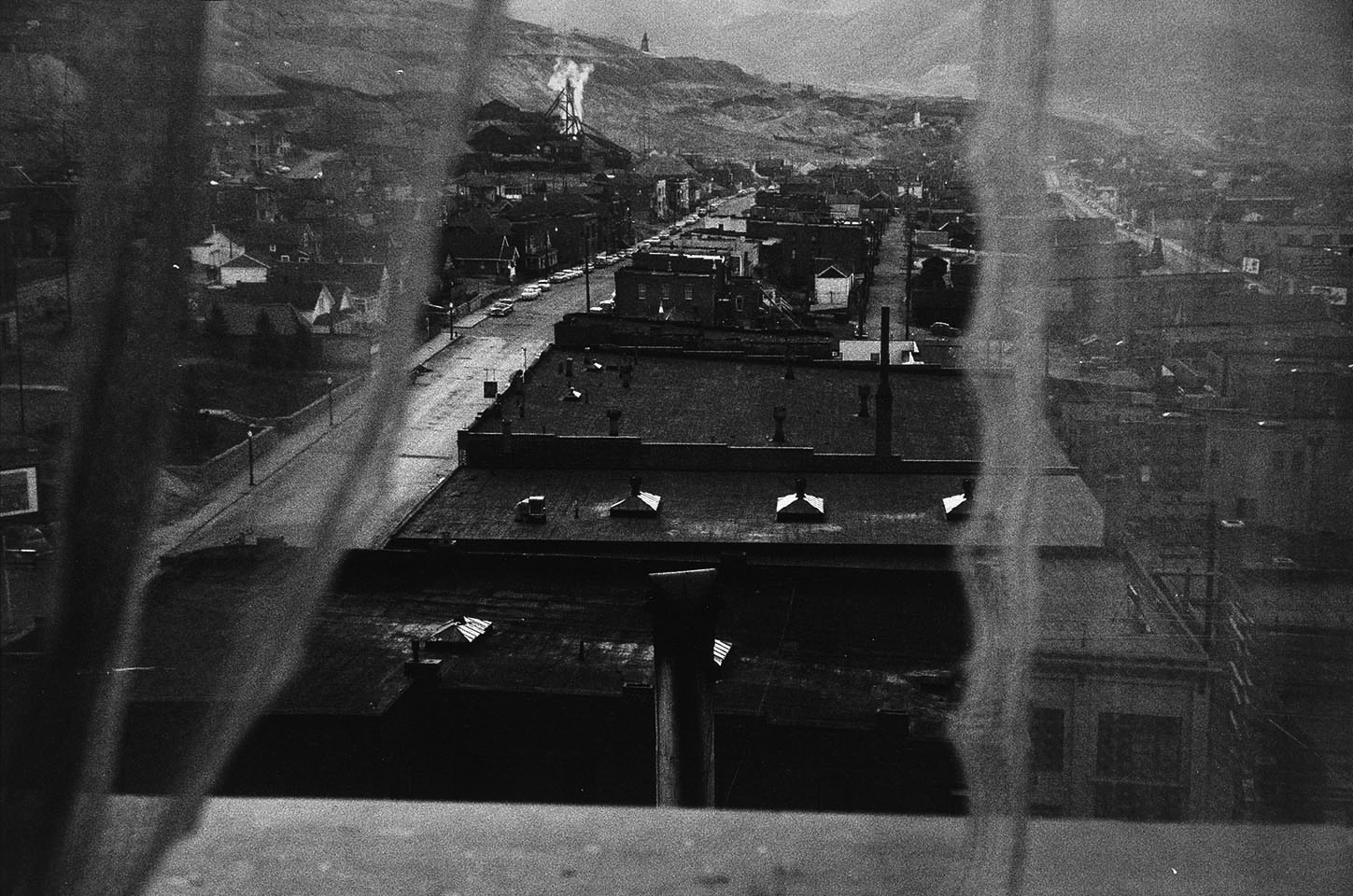

#21) My favorite Robert Frank picture is his View From A Hotel Window in Butte, Montana. It is both a picture of Butte and a self-portrait:

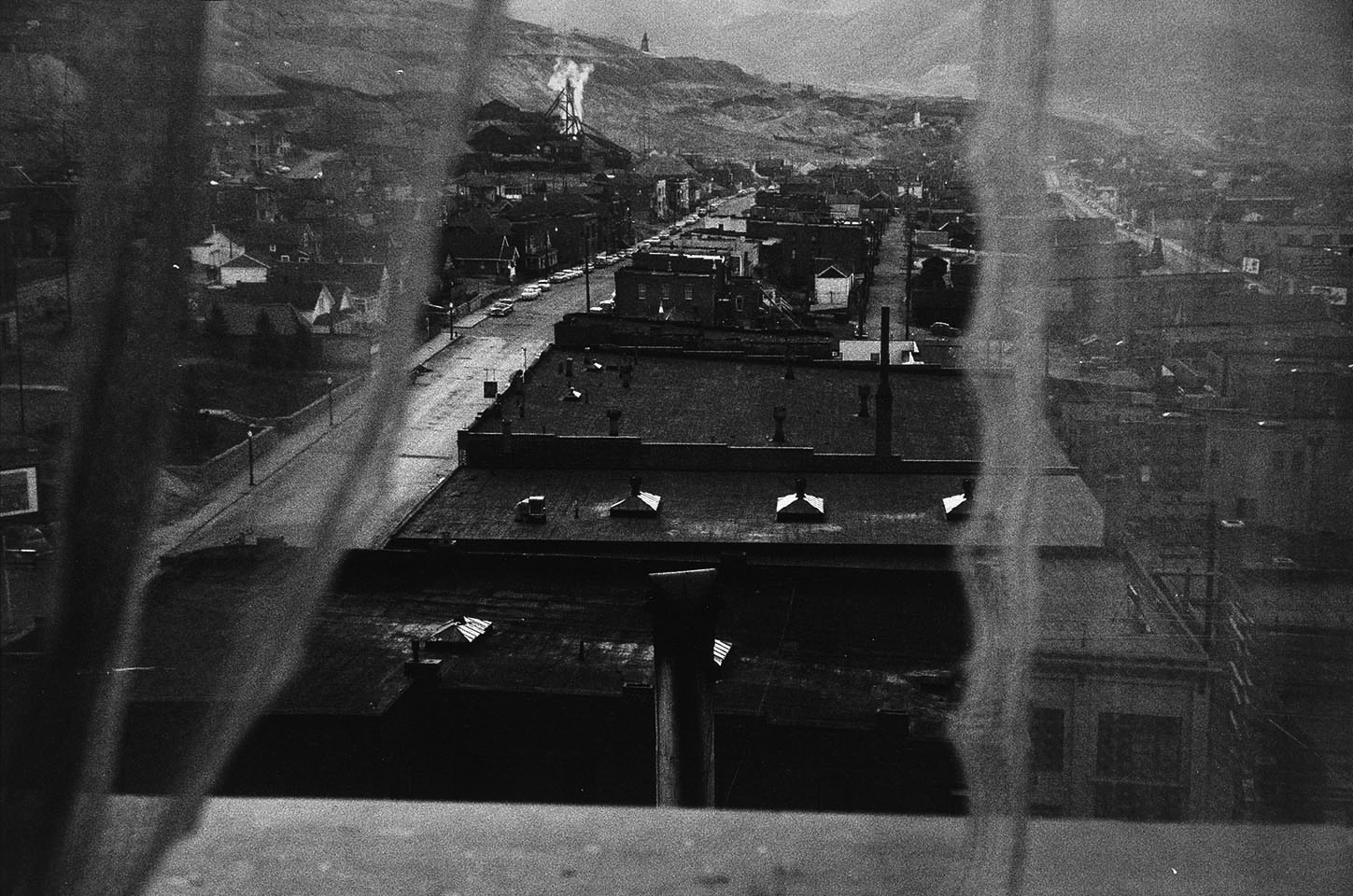

#22) I lose Frank when he makes pictures like Sick of Goodby’s (1978)

#23) In 1977 Robert Frank said something in an interview that might just be the mission statement for the entire Little Brown Mushroom enterprise: “If I continued with still photography, I would try to be more honest and direct about why I go out there and do it. And I guess the only way I could do it is with writing. I think that’s one of the hardest things to do—combine words and photographs. But I would certainly try it. It would probably fail; I have never liked what I wrote about my photographs yet. That would be the only way I could justify going out in the streets and photographing again.”

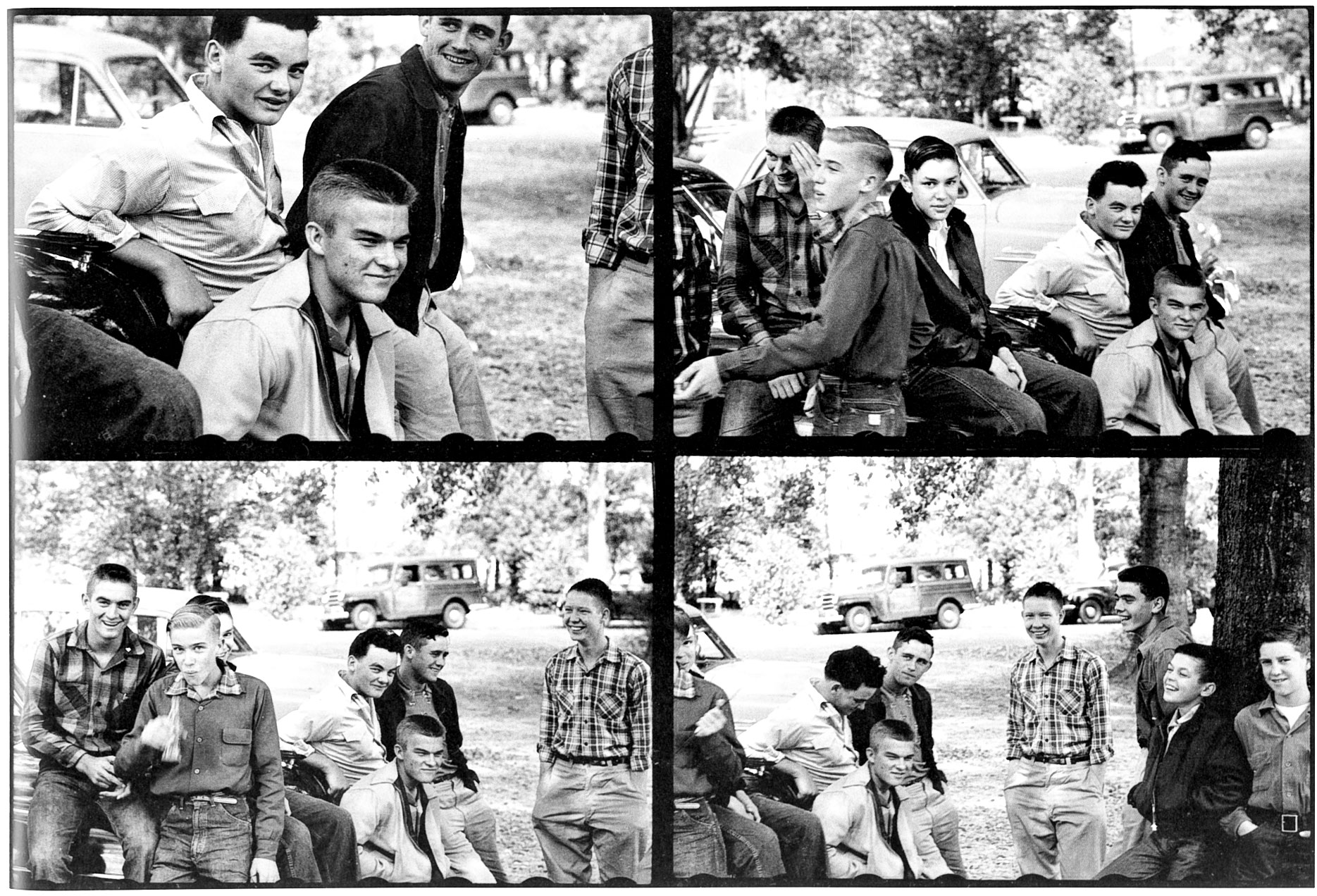

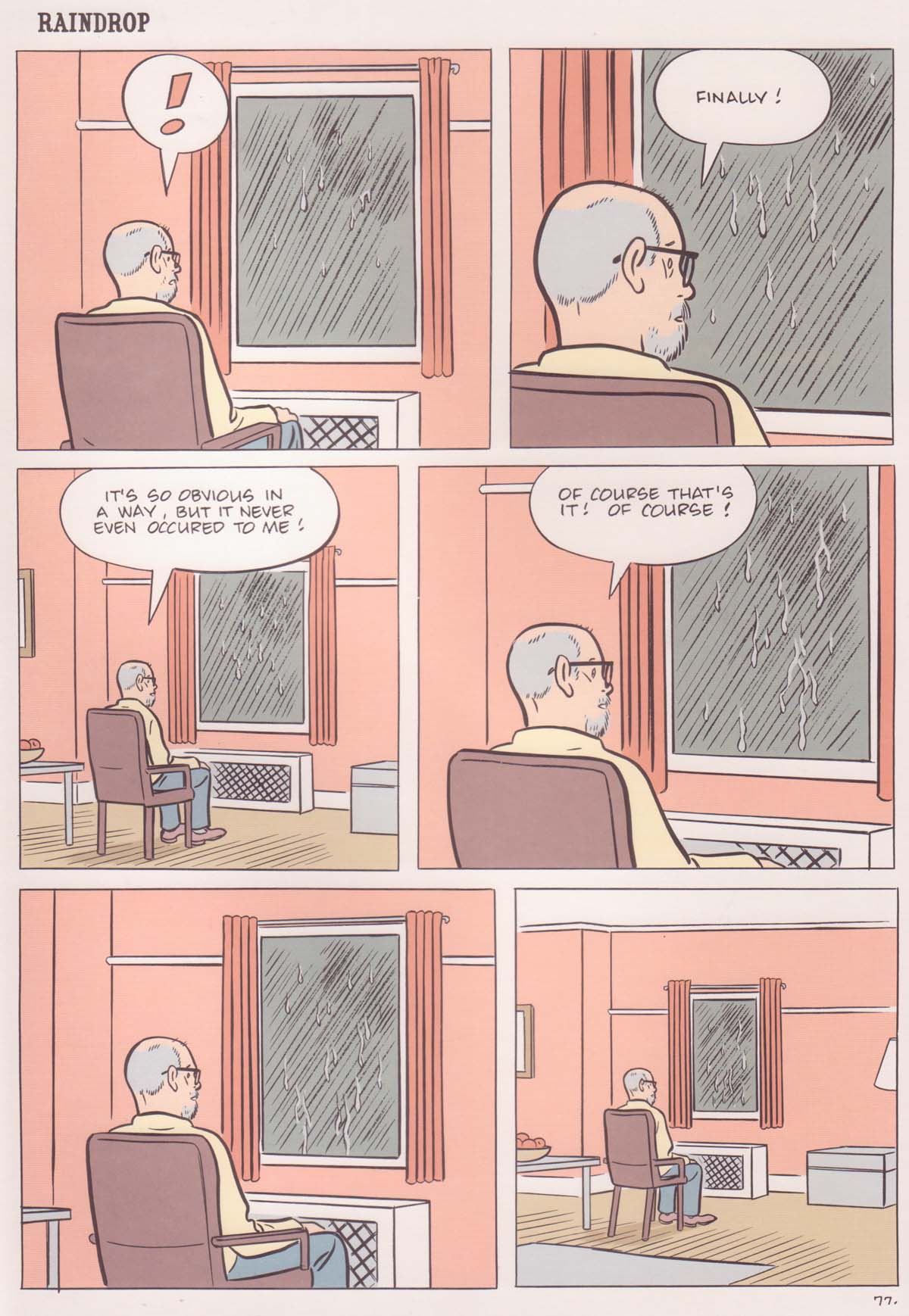

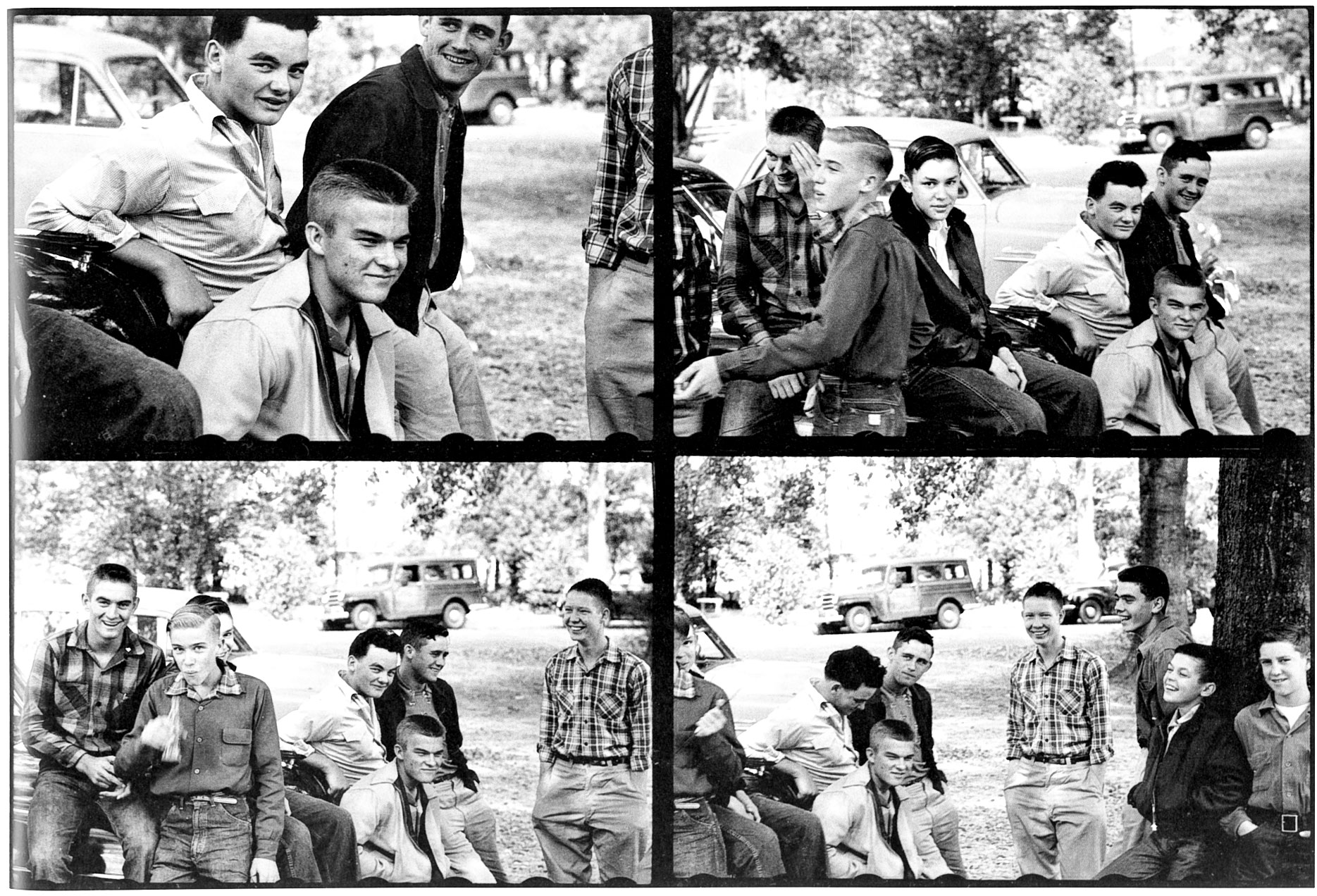

#24) In Lines of My Hand (1972) Robert Frank shows four pictures of smiling high school kids from Port Gibson Mississippi:

#25) The picture is accompanied by the following text:

KIDS: What are you doing here? Are you from New York?

ME: I´m just taking pictures.

KIDS: Why?

ME: For myself – just to see…

KIDS: He must be a communist. He looks like one.

Why don´t you go to the other side of town and watch the niggers play?

#26) Shield’s ends Reality Hunger with a quote from Anne Carson’s book Decreation:

#27) Number Six-Hundred-Eighteen: Part of what I enjoy in documentary is the sense of banditry. To loot someone else’s life or sentences and make off with a point of view, which is called “objective” because one can make anything into an object by treating it this way, is exciting and dangerous. Let us see who controls the danger.