Last week I participated in a panel discussion at the Museum of Modern Art on the topic of American photography. Using Walker Evans as a springboard for the conversation, the panelists were asked to discuss how one defines American photography in an increasingly global context. During this conversation, I thought often of my recent trip to Bogotá, Colombia. While I was there, I visited the home of a young photographer named Mateo Gómez Garcia. Gomez is a student of global photography and his work is clearly inspired by the North American tradition initiated by Walker Evans. Nevertheless, working from his rural home on the outskirts of Bogotá, Mateo is grappling with a distinctly Colombian sense of identity.

As part of the ongoing series of posts fototazo and I have done on contemporary Colombian photography, I thought I would follow up with Mateo to get his perspective as an up-and-coming Colombian photographer. Many thanks to Tom Griggs of fototazo for translating our dialog.

Alec Soth: You are 25. Do you feel like you’ve reached artistic maturity?

Mateo Gómez Garcia: I feel that I am increasingly strengthening a personal language, however in this process I have tried to be as cautious as possible as far as falling into a fixed style or a formula for producing photographs. Instead, I stay attentive when working on a new project, trying to include new approaches without separating completely from a personal style.

Alec Soth: This desire to find a formula or quickly identifiable style is something quite common in every culture, I suspect. But I gather that your path to educating yourself as a photographer is somewhat atypical of young photographers in the US and Europe. Do you have a sense of those differences? What is your feeling about photographic education in Colombia?

Mateo Gómez Garcia: I would not know how to describe an “academic” education in Colombia, if that is indeed the type of education you are asking me about, because I did part of that type of education in Argentina. However almost 80% of my education I have done on my own, taking pictures and looking at a lot of photography. I think Colombia is a very rich center for producing photography. A restless photographer, who knows what’s going on in photography worldwide and who has a clear vision of what they want to do here in Colombia, will have the tools they need to generate an interesting body work.

Alec Soth: I’m wondering how you feel about the issue of national or regional identity. Is being from Colombia, and Bogotá specifically, something you want to be associated with your work, or not? And do you think Colombian photographers generally should embrace this regional identity, or separate from it.

Mateo Gómez Garcia: Very good question! My work is exactly about the subject of identity. I would not say I define the country as it might sound pretentious, but I give my personal opinion of what I see in the country, using each of my projects as an excuse to address this issue of identity. I think the issues of violence, drugs and conflict are important, but have already been done many times. I guess every photographer has their concerns and ambitions like I do, however I also think that there are some roads that are easier than others – talking about the issue of violence etc. I also think to refresh photography here in Colombia it is important to have a more global view of what is being done elsewhere in the world.

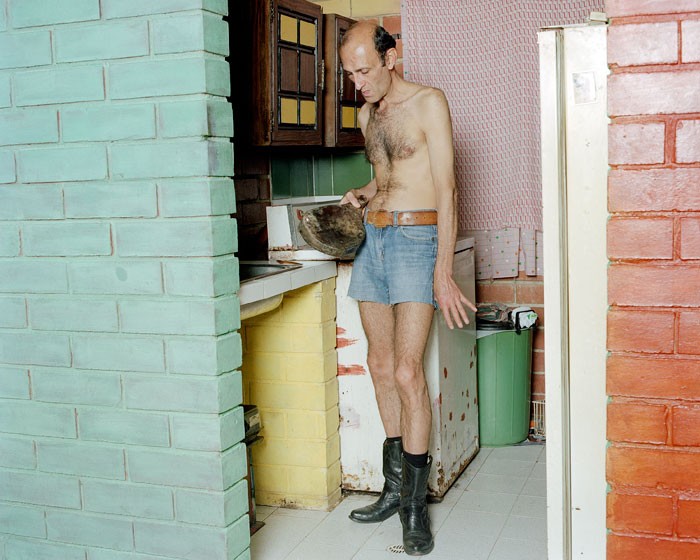

Alec Soth: That brings us to talk about your work and your current project, A Place To Live. What brought you to start this project? Was it initiated by an idea or by personal experience?

Mateo Gómez Garcia: The project started with an idea and a personal experience. For 10 years I have lived in one of the towns most affected by urban development in the savannah of Bogotá. La Calera, my home, has seen drastic changes during that time: new developments, residential clubs and shopping centers.

“A Place To Live” began as a very focused documentary project to make a record of the virgin land about to be urbanized in Bogotá and its closest municipalities. However with the passage of time it became a record of both the Colombian household and the change of rural life to urban life.

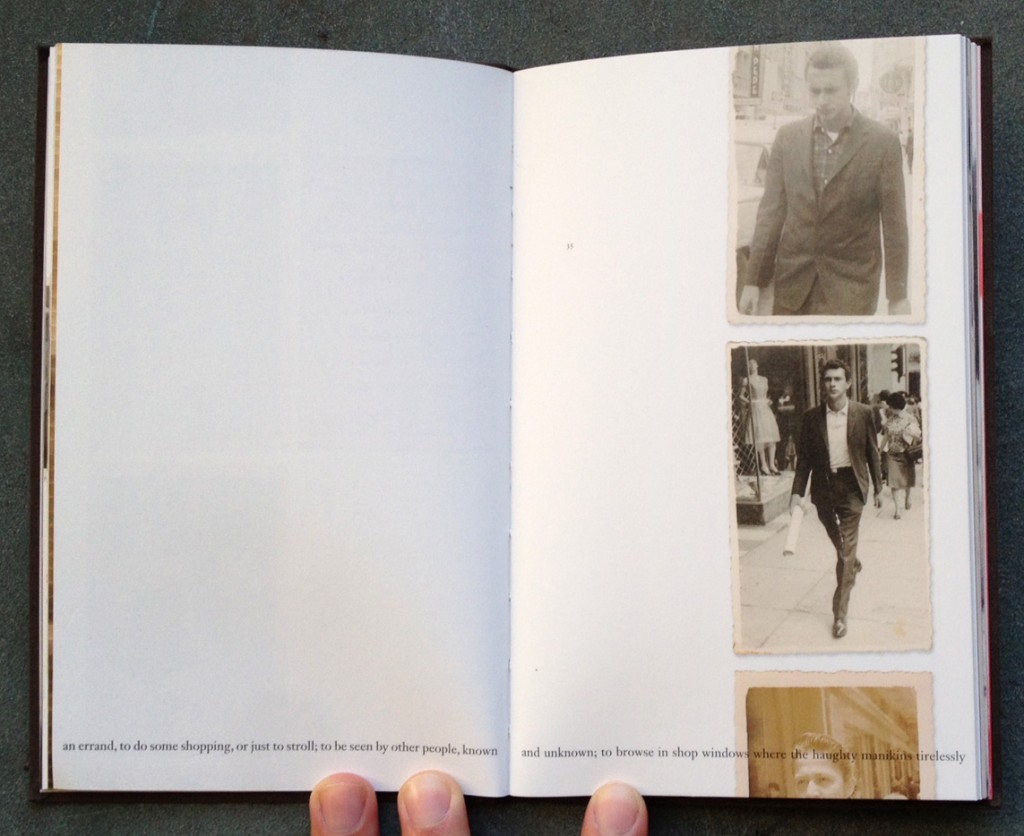

To make a photographic project that looks at so many issues and still suggests a reading which proposes certain narrative coherence was a job that took me almost 3 years. One of those themes that “A Place To Live” tries to suggest is the theme of memory and with the photograph itself being an ambiguous medium, it is largely a record of the past. You have to imagine it as a family album, with a nostalgia for that which no longer exists.

Alec Soth: I’m interested in the issue of nostalgia as it pertains to age. When I was in my twenties, I had nostalgia for the culture of the late 1960’s (the time when I was born). I find it fascinating now to work with young people who are nostalgic for the 1990’s. Is there a particular era in Colombia that evokes this quality of nostalgia for you? Is this something unique to you and your generation, or are people in Colombia generally nostalgic for a time in the country’s history?

Mateo Gómez Garcia: Ha ha! Well, for me the 90s were times in which I learned what it means to be from a country in which the main protagonist is terror.

It was an era in which both the Medellín and Cali drug cartels fought the government and even to go out for ice cream was a risk, as there were always bombings, in central areas and elsewhere. And if you wanted to leave the city by car you could be a victim of the so-called pescas milagrosas (“miracle catches”) – guerrilla checkpoints with the potential for mass kidnappings – so it really was to be at a crossroads.

For me nostalgia comes from the era of my parents! As well as from the 60s and 70s! As you know I didn’t live those decades, but my grandmother on my father’s side documented all of the trips of my uncles and my father to my grandfather’s farms as an amateur photographer – the waterfalls, the barbecues on the plains, my great-grandfather drinking his whiskey from 6 pm, and my father with his various girlfriends – ha ha! They are times which now are impossible to recreate because my grandfather died and my grandmother is very old and therefore my family is very fragmented.

See more of Mateo Gómez Garcia’s work HERE