During our recent Summer Camp for Socially Awkward Storytellers, one of the participants made a compelling point about children’s books. He said that when he thinks about these books, he rarely remembers the story. For him, the book is more of a place than it is a story.

After reflecting on this argument, I found myself agreeing. The place that a story takes me is more important than the mechanics of how I get there. But the story, more often than not, is the vehicle for getting there.

But that doesn’t mean this vehicle needs to be anything fancy. In preparation for camp, I watched a video by Ira Glass on creating radio stories. Glass defines a story as simply being a sequence of actions. “A story in its purest form,” says Glass, “is someone saying ‘this happened, and it led to this next thing, and that led to this next thing.’” A story doesn’t have to have an Aristotelian arc, or any sort of plot whatsoever.

I thought about this simple definition while reading the nine short stories by the legendary Manga/Geika artist Yoshihiro Tatsumi collected in the book Good-Bye. Some of the stories in the collection have dramatic tension, but most are a straightforward series of actions.

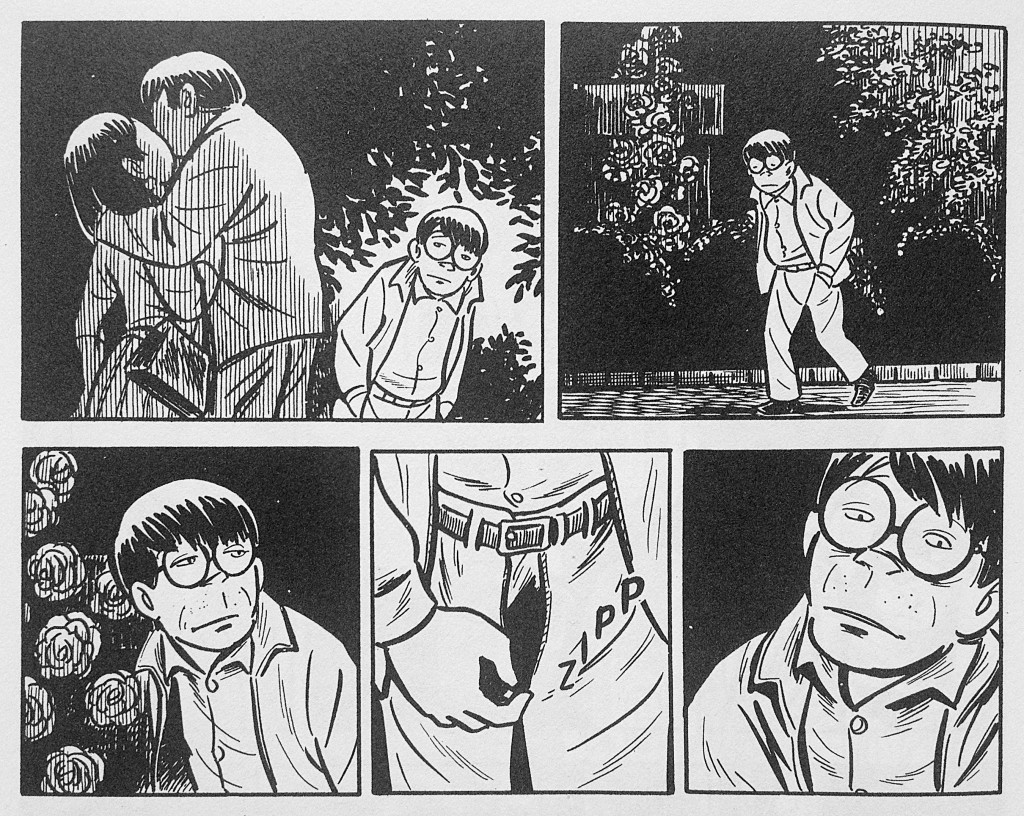

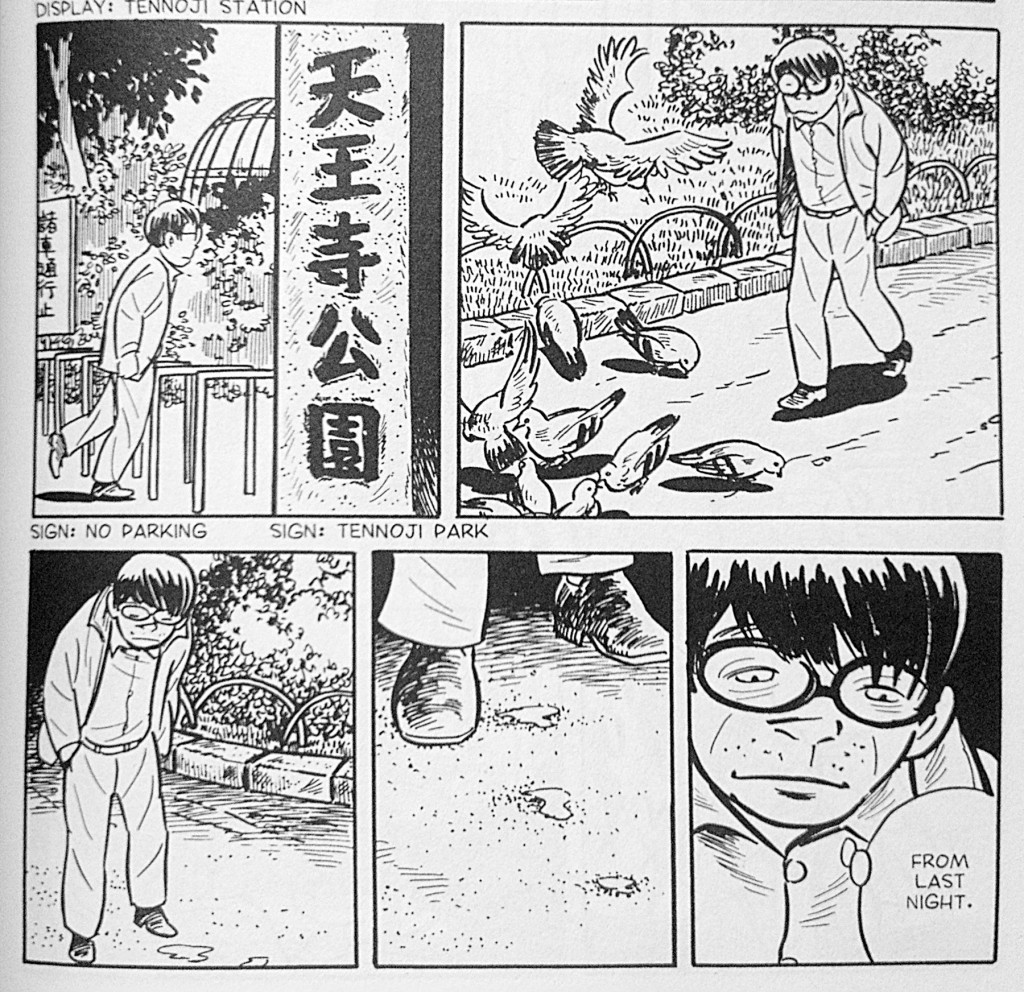

One of my favorite stories, for example, is ‘Night Falls Again.’ It starts with a homely young man at a peep show being called a pervert by a stripper. He leaves, follows a pretty girl on the street, and gets called a pervert again. In a park, after seeing a couple make out, he masturbates. On the train home, he vomits. The next morning while walking in the park, he sees pigeons pecking at his semen from previous night. After going to work and being ridiculed by his boss, he walks the streets at night and stares at more women. The story ends with him going back to the peep show.

This story has absolutely no plot. And with the exception of the pigeons, noting memorable happens. But the desperately lonely place this story took me was unforgettable.

Would I be able to get to the place if the story was removed? I’m imagining a series of photographs: a stripper, a girl on the street, pigeons, vomit, more girls on the street. It sounds gritty and potentially engaging. But what about those pigeons? Without knowing the story of the protagonist, would the image be so unforgettable?

…really enjoyed this thread as I’m very interested in story telling in general and just in the process of finishing a related photography project, the images all the result of one aimless walk/wander. While going through these photographs I became very aware that, on the one hand, there wasn’t any story and this was never the intention. On the other hand, once I pieced the images together in the order they were taken, I quickly came to the conclusion that the body of work would more than likely be perceived as a story, despite my intentions to the contrary, viewers would look for the plot…

…maybe it’s to do with images being ingrained so deeply in the development of our communication i.e. cave paintings, petroglyphs, alphabet…the fact is the moment we are faced with any image a scanning and decoding process begins as we try to understand and this is obviously based on our cultural and social background and personal experiences. I wonder whether, when presented with a body of work, we are conditioned to expect a story. I’m suggesting that may be we subconsciously prepare ourselves and respond differently to a collection of work as opposed to a single image.

Will definitely check out Good-Bye.

P.S. strangely enough, one of the photographs in the project mentioned is a grid of 9 images of pigeons eating something.

A small nit to pick: “Night Falls Again,” as you recount it, most certainly has a plot. It may have no resolution, and be circular and minimalistic, perhaps even existential, but it has a plot.

To take the broad (and un-cited) definition provided at wikipedia, which matches most writing blogs/resources that come up for a google search of “plot”:

“Plot is a literary term defined as the events that make up a story, particularly as they relate to one another in a pattern, in a sequence, through cause and effect, how the reader views the story, or simply by coincidence. One is generally interested in how well this pattern of events accomplishes some artistic or emotional effect.”

Here, we have a main character. Something happens to him. He reacts. He has an emotional response to his reaction (implied). The cycle in which he is trapped begins again.

Samuel Beckett would be proud of this plot.

I think the story is powerful because it shows the essential loneliness of the character and his paths, however repellent, to feeling good even for only a few moments. The story is about his intense feelings and drive toward happiness as well as his inability to connect with other people in mutually satisfying ways.

Thank you for the follow-up Alec. I like the E.M. Forster example because it sheds more light for me on why “Night Falls Again” is such an interesting story from a critical perspective. It is because the plot (“the causality of a series of events”) is entirely implied: it relies on the reader to draw the causal conclusions in their own mind. This can be (and here is) a very powerful mechanism. To draw an analogy to rhetoric, delivering the facts of a case in such a way that the listener arrives at the conclusion you desire on their own (i.e., they convince themselves) is immensely more powerful than simply arguing your conclusion.