Monday stares through the viewfinder, a black hood over his head. – from Littlefoot by Charles Wright

When Brad Zellar and I hit the road for The LBM Dispatch, we’re primarily looking for stories. Our most recent trip, Three Valleys, was no different. Both Silicon and San Joaquin Valley offered up countless leads. But Death Valley was something different. The land felt as stripped of story as it was of vegetation. This proved to be a significant challenge. Despite having produced several books with geographical titles, I’ve never considered myself a landscape photographer. More often than not, I just use geography to hang my metaphorical hat on.

When Brad Zellar and I hit the road for The LBM Dispatch, we’re primarily looking for stories. Our most recent trip, Three Valleys, was no different. Both Silicon and San Joaquin Valley offered up countless leads. But Death Valley was something different. The land felt as stripped of story as it was of vegetation. This proved to be a significant challenge. Despite having produced several books with geographical titles, I’ve never considered myself a landscape photographer. More often than not, I just use geography to hang my metaphorical hat on.

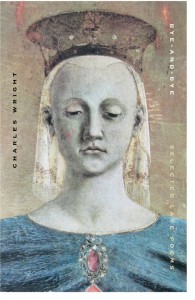

While I was in Death Valley, I thought of different landscape artists that might be of assistance. The one that most prominently came to mind was Charles Wright. I wasn’t sure why. Wright’s poetry has nothing to do with the desert. He’s very much a Southerner (perhaps it was because I spent so much time on this trip with the excellent Southern photographer McNair Evans). At any rate, after leaving Death Valley, I went to City Lights in San Francisco and picked up Charles Wright’s recently published collection of late poems, Bye-and-Bye.

The book didn’t disappoint. Virtually every poem in Bye-and-Bye deals with nature and geography. But over and over again, this landscape reveals Wright’s search for spiritual meaning – something Death Valley also invariably evokes:

The structure of landscape is infinitesimal,

Like the structure of music,

seamless, invisible.

Even the rain has larger sutures.

What holds the landscape together, and what holds music together,

Is faith, it appears–faith of the eye, faith of the ear.

– from ‘Body and Soul II’

My ‘faith of the eye’ was tested more than once in Death Valley. After crossing one pass, I saw a giant lake gleaming in the distance. As we drove closer, I could see people the size of ants walking on its surface. Only when we pulled up to its edge could I decipher the illusion. The ‘lake’ was a bed of salt. Nonetheless, the scene looked like a Hollywood depiction of heaven. I tried to take pictures of this illusion, but the results were corny:

I guess this is why I was compelled to read Wright. He’s able to address the big issues behind our engagement with landscape in a way that feels honest, humble and real:

Why, It’s Pretty as a Picture

A shallow thinker, I’m tuned

to the music of things,

The conversations of birds in the dusk-damaged trees,

The just-cut grass in its chalky moans,

The disputations of dogs, night traffic, I’m all ears

To all this and half again.

And so I like it out here,

Late spring, off-colors but firming up, at ease among half things.

At ease because there’s no overwhelming design

I’m sad heir to,

At ease because the dark music of what surrounds me

Plays to my misconceptions, and pricks me, and plays on.

It is a kind of believing without belief that we believe in,

This landscape that goes

no deeper than the eye, and poises like

A postcard in front of us

As though we’d settled it there, just so,

Halfway between the mind’s eye and the mind, just halfway.

And yet we tend to think of it otherwise. Tonight,

For instance, the wind and the mountains and half-moon talk

Of unfamiliar things in a low familiar voice,

As though their words, however small, were putting the world in place.

And they are, they are,

the place inside the place inside the place.

The postcard’s just how we see it, and not how it is.

Behind the eye’s the other eye,

and the other ear.

The moonlight whispers in it, the mountains imprint upon it,

Our eyelids close over it,

Dawn and the sunset radiate from it like Eden.

What gave me the most pleasure reading Wright was less his description of landscape than his ability to use landscape as a vehicle for exploration. Fundamentally, this exploration is literary. But for Wright, literary exploration creeps right up to the edge of spiritual epiphany. It gives Wright something to believe in.

Whenever I start feeling bad about my skills as a landscape photographer, I’m going to reread Wright and this perfect little battle cry:

The Minor Art of Self-Defense

Landscape was never a subject matter, it was a technique,

A method of measure,

a scaffold for structuring.

I stole its silences, I stepped to its hue and cry.

Language was always the subject matter, the idea of God

The ghost that over my little world

Hovered, my mouthpiece for meaning,

my claw and bright beak…

I have made photos in Death Valley and it is the classic minimalist landscape. And like the North Shore of lake Superior It changes all the time throughout the day. I really found some interesting things where human activity meets the desolation.

I can imagine you doing well in that environment Chris. I have similar problems on the North Shore. The more pure the landscape, the more I struggle.

I haven’t forgotten to record Bly’s “A Home in Dark Grass” for you, to cd. I should think what you’ve hit upon here may work in tandem with the recording. I have just purchased Wright’s first few books last month, “China Trace”, “The Grave of the Right Hand” . . . I was interested to see how his time in Italy (while in the service) ignited his take on the landscape and began his launch into poetry and the limitless potential of language. Since early adolescence and onward to the present, Wright is on a constant search for salvation by trying to compose intangible, spiritual meanderings and memories into language with great assistance from the landscape. With each book one can see a further transformation of Wright and an increasing dynamic of the English language, where nouns become verbs, verbs become place, memories become blue mountains . . . anyone making landscape photographs, paintings, etc on foreign, non-maternal soil fools themselves silly in thinking they’ll make great pictures of the natural world. All’s you can hope for are photographs illustrating a soul-searching and the failure that comes with being a human being, who is infected with a biological need to find form in all facets of nature. It’s the searching and tiny failures that make landscape photography interesting. I see that in your photograph above . . . the immensity of nature and the tiny, frail beings that we are, but nonetheless critical to fulfilling the message of landscape art. Charles Wright is a great guide. And God bless Mr. Robert Adams. We have another savior there to turn to, certainly in words, too, with “Why People Photograph.” Now I must go purchase “Bye-And-Bye”. Another collection of his that I believe essential – “County Music”. Thanks for the popsicle, stanzas and landscape! Beautiful!

Thanks so much for your thoughtful comments Michael. Totally agree that Adams is an essential guide (the Robert, not the Ansel…who is always the first to come to mind when confronted with such immensity).

Cheers, Alec.

I found this lengthy, insightful interview recently with Wright (Paris Review), should you get some down time. http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2369/the-art-of-poetry-no-41-charles-wright

“The more pure the landscape, the more I struggle.”

This acknowledgement reminds me of a similar sentiment I came across in an interview: “Right now I’m trying to learn how to do landscapes. They’re incredibly hard.” —Lee Friedlander (1992)

To all this and half again….wonderful post Aec. Great poetry too; Wright is magnificent.