“He grabbed the kid by the coat, rolled him over, roughly sat him up. The kid’s shivers made his shivers look like nothing. Kid seemed to be holding a jackhammer. He had to get the kid warmed up. How to do it? Hug him, lie on top of him? That would be like Popsicle-on-Popsicle.”

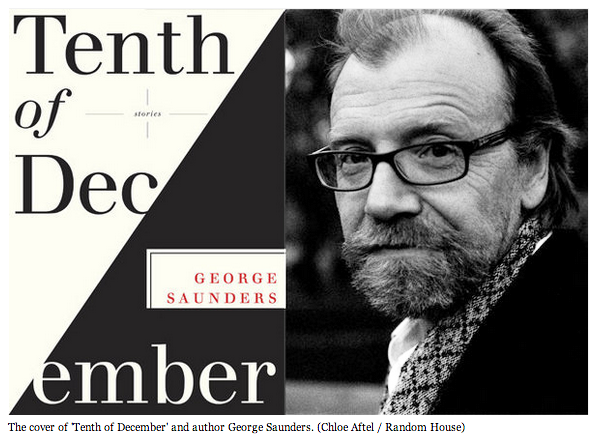

From “Tenth of December” by George Saunders

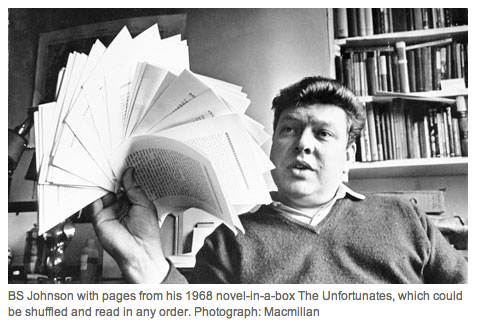

While preparing last week’s assignment on Building Stories by Chris Ware, I learned about another book in a box, The Unfortunates, by B.S. Johnson. Published in 1969, the box consists of 27 pamphlets that can be read in any order (except for the ones marked ‘first’ and ‘last’).

The subject of this fragmentary memoir was instigated by Johnson’s trip to Nottingham as a sportswriter covering an inconsequential soccer match. The city brings back memories of an old friend who died of cancer and an old lover who left him. The unordered pamphlets function like memories bubbling up in the author’s consciousness during his weekend in Nottingham.

While the writing in The Unfortuantes is excellent, reading it after Building Stories was a letdown. Part of this is due to the absence of Ware’s gorgeous artistry, but something else nagged at me. I found myself irritated with the narrator of The Unfortunates.

Johnson is a card carrying solipsist, and as such, wildly egocentric. When he first learns of his friend Tony’s cancer, for example, he complains that Tony and his wife didn’t attend the publication party of his new book: “I was annoyed, angry even, that he, and that both of them, should find any excuse for missing something so important, that its importance to me should not be shared by them.”

Johnson is adamant that art speak the truth. Though defining himself as a novelist, Johnson was opposed to fiction. “Telling stories is telling lies,” he famously wrote, “The two terms, truth and fiction, are opposites.” Consequently, the pamphlets in The Unfortunates read less like a novel than like artful Facebook status updates from a depressed, self-absorbed acquaintance.

While reading The Unfortunates, I kept thinking about the George Saunders quote I mentioned in last week’s post:

I began to understand art as a kind of black box the reader enters. He enters in one state of mind and exits in another… The writer… can put whatever he wants in there. What’s important is that something undeniable and nontrivial happens to the reader between entry and exit… The black box is meant to change us.

Having felt that nothing “undeniable and nontrivial” happened to me while reading The Unfortunates, nor having felt like I’d had a popsicle of pleasure, I figured I’d give Saunders’ writing a try. I thought it would be particularly interesting to read the title story in his new book, “Tenth of December,” since it deals with a man dying of cancer.

I ended up reading the story on my iPhone while putting my six-year old to sleep. As his breathing slowed, I felt my own pulse quicken. Saunders’ story about a cancer patient who encounters a pre-teen oddball while trying to kill himself reads like a potboiler. I couldn’t scroll down the screen fast enough. But this isn’t to say that the story felt melodramatic. As we watch these characters collide, we are also witness to their scattershot interior monologues. These voices felt just as honest as anything Johnson wrote in The Unfortunates.

In an interview with the New Yorker about his “Tenth of December” story, Saunders explained what he was looking for with these voices:

Lately I find myself interested in trying to find a way of representing consciousness that’s fast and entertaining but also accurate, and accounts, somewhat, for that vast, contradictory swirl of energy we call “thought,” and its relation to that other entity, completely unstable and mutable, that we put so much stock in and love so dearly, “the self.” That is, of course, an impossible task, the mind being so vast and prose being so inadequate. But it seems to me a worthy goal: try to create a representation of consciousness that’s durable and truthful, i.e., that accounts, somewhat, for all the strange, tiny, hard-to-articulate, instantaneous, unwilled things that actually go on in our minds in the course of a given day, or even a given moment.

This seems very similar to what Johnson was looking for with his narration. While reading “Tenth of December,” I kept wondering what B.S. Johnson would have made of it. Had he read the story on November 13th of 1973, would he still have committed suicide?