In a recent article about Songbook in The Daily Beast, the influence of my high school teacher was discussed:

It was also growing up in Minnesota when he [Soth] first began learning about photography from his teacher, Bill Hardy, who he still keeps in touch with to this day and works with on educational projects. “He’s a remarkable guy, and he would really encourage us to get out of the classroom and take walks and explore. I remember his first lesson was without a camera. He would just have us walk with cardboard mats with windows cut-out and we’d look through them,” he recalls. “It was a good lesson, but I didn’t take to it originally.”

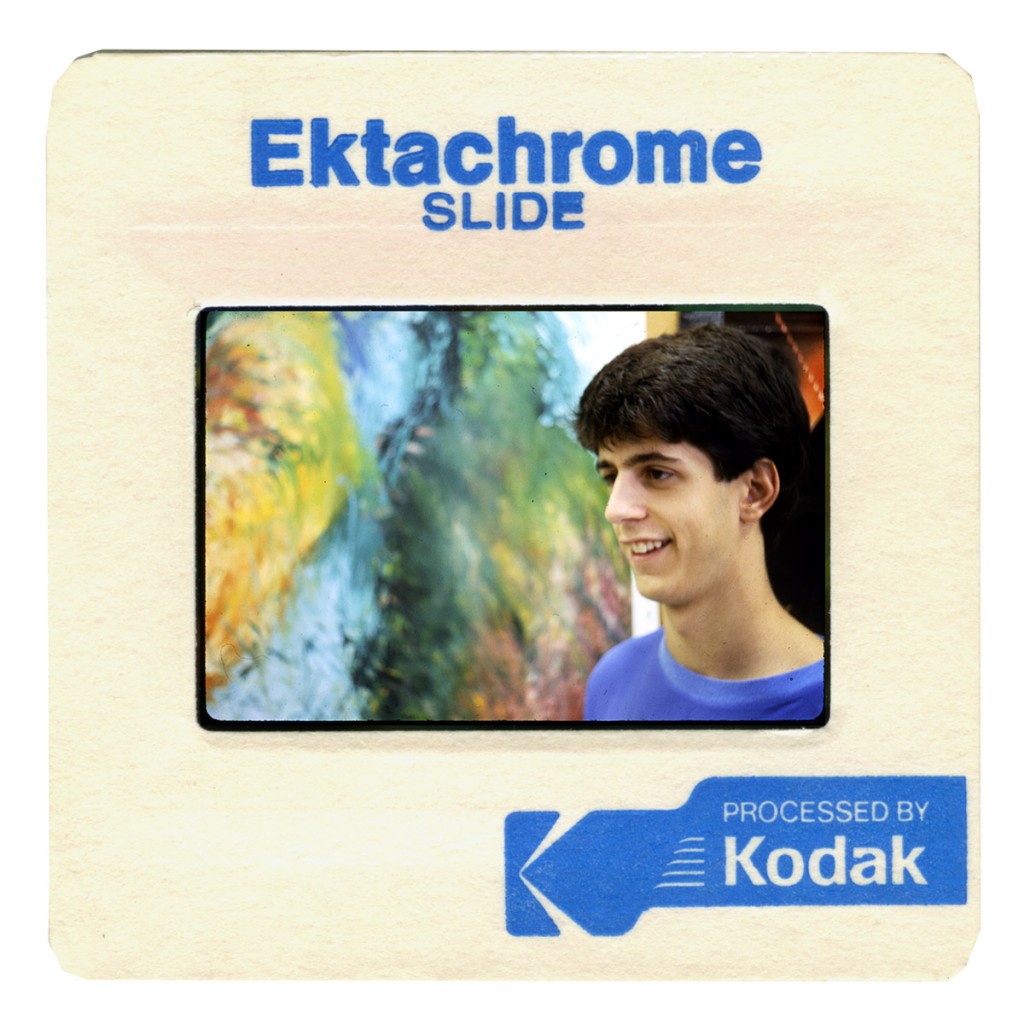

While I might not have fallen in love with photography at first, I did fall in love with making art (that is one of my paintings in the background):

I’m absolutely certain I wouldn’t be a photographer were it not for Mr. Hardy’s attention and encouragement. I owe him so much. So when Mr. Hardy invited me to spend this week with his colleague Walker Zeiser and their students in upstate New York, I didn’t hesitate. For the last twenty or so years, Mr. Hardy has run a program called Sideroads at Millbrook Academy. With notebooks and cameras, students go out and explore neighboring communities. Over the past week we’ve visited the towns of Hudson, Saugerties, Beacon and Housatonic for a project we called Lurking Beyond Millbrook:

freezing outside of The Housie Market in Housatonic

freezing outside of The Housie Market in Housatonic

I decided to use my time here to write rather than to photograph. For me this week has been, among many things, a chance to reflect on how my ways of seeing the world have changed since I was sixteen.

In Saugerties, I spent most of my time in the wonderful Inquiring Minds bookstore and cafe. I purchased Book 1 of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s celebrated novel, My Struggle. I was taken aback when, on page 11, Knausgaard seemed to sum up the feeling I had about age and learning:

As your perspective of the world increases not only is the pain it inflicts on you less but also its meaning. Understanding the world requires you to take a certain distance from it. Things that are too small to see with the naked eye, such as molecules and atoms, we magnify. Things that are too large, such as cloud formations, river deltas, constellations, we reduce. At length we bring it within the scope of our senses and we stabilize it with fixer. When it has been fixed we call it knowledge. Throughout our childhood and teenage years, we strive to attain the correct distance to objects and phenomena. We read, we learn, we experience, we make adjustments. Then one day we reach the point where all the necessary distances have been set, all the necessary systems have been put in place. That is when time begins to pick up speed. It no longer meets any obstacles, everything is set, time races through our lives, the days pass by in a flash and before we know what is happening we are forty, fifty, sixty… Meaning requires content, content requires time, time requires resistance. Knowledge is distance, knowledge is stasis and the enemy of meaning.

What Knausgaard is getting at, in part, is that meaning is for the young and knowledge is for the old. We’re lucky when the old, with their knowledge, help guide the young toward meaning. Bill Hardy has spent the majority of his life doing just that. As time picks up speed for me, the question I’m facing is whether or not I’ll be able to do this for someone else.