It’s been 10 years since the second U.S. invasion of Iraq and 12 years of American casualties in Afghanistan. Everyone’s exhausted, Big Media can’t seem to find a story. Until Iran becomes the next Iraq, no war news seems to be good war news.

Unfortunately the deaths continue despite the news cycle: Sixteen American dead in Afghanistan in March alone. You might be surprised by this fact if you watched CNN 24/7, but you’d know it in the pit of your stomach if you tuned into the PBS NewsHour every night. That’s because, starting on March 31, 2003, 11 days after the war in Iraq began, the NewsHour has been broadcasting a short list of service men and women who have died in the conflict as they become available from the Department of Defense. The casualties appear in two’s or fives’ or ten’s every night for a week, sometimes two nights per week, week after week, month after month, year after year. Titled “Honor Roll,” the segment expanded in 2006 to include soldiers killed in Afghanistan, where they are still dying and still appearing in the NewsHours’ final segment.

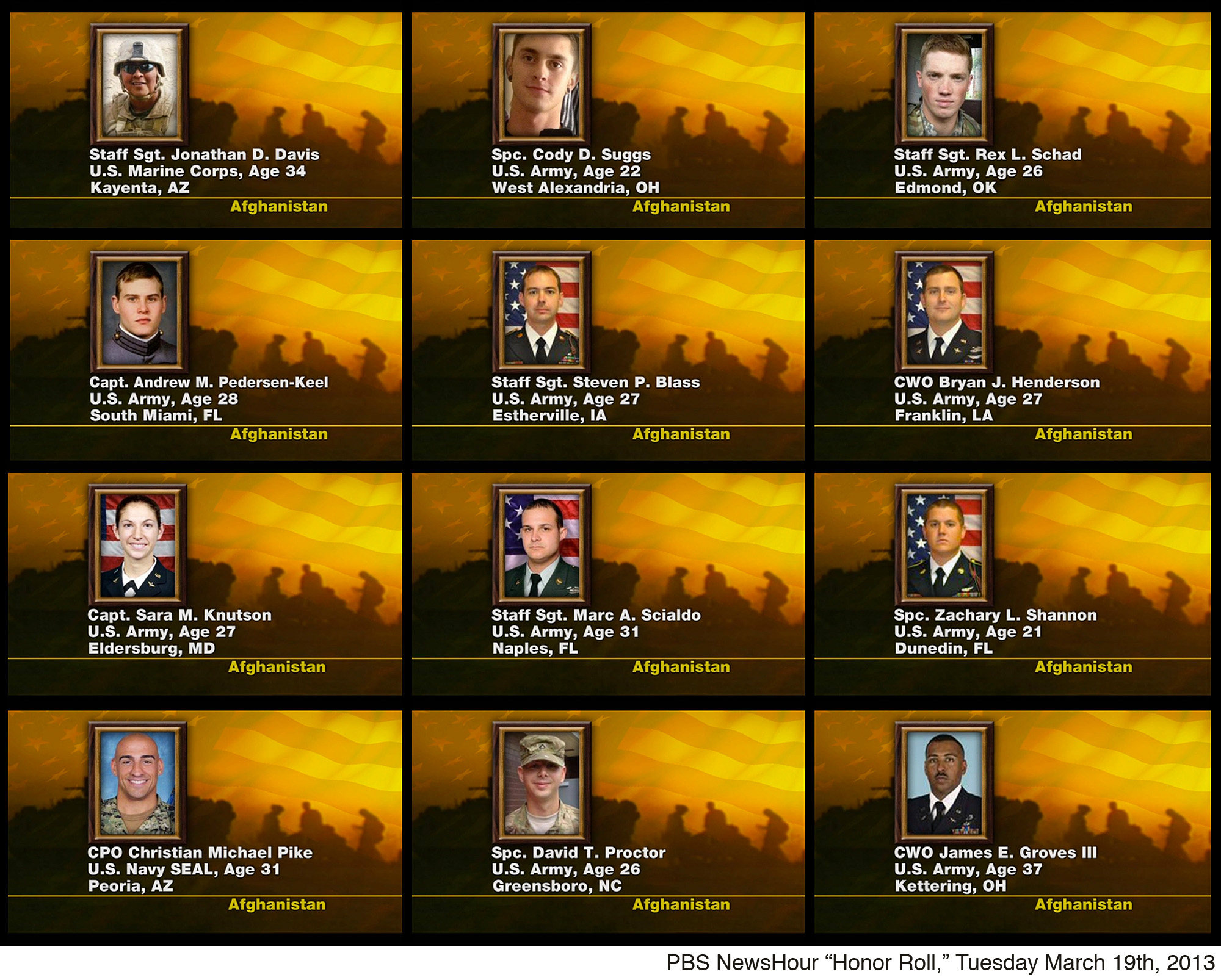

The format is deceptively simple. Each soldier is represented for a few seconds onscreen by a photograph along with his/her age, service branch, rank, and hometown. One soldier after another, for as long as it takes, the entire segment runs in complete silence. Even though there’s a silly background illustration of flag, soldiers, and desert, the reportage could hardly be more direct or objective. There is no comment, no break in the solemn procession of dead, no action to relieve the sense of loss. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, the NewsHour has used its nightly schedule to create one of the most innovative and powerful instruments of wartime reportage since 16mm cameras brought Vietnam to the nightly news.

It’s not the first time photographs of casualties have been used to make a point about the nature of war. After reviewing the photographs Alexander Gardner had made at the Battle of Antietam, Mathew Brady decided to exhibit 21 large views of piles of corpses in his New York gallery with the simple title: “The Dead of Antietam.” Life Magazine famously published “The Faces of the Dead in Vietnam: One Week’s Toll” consisting of 242 small portraits in the June 27, 1969 issue. Both Brady’s exhibition and the Life article were unabashed attempts to shock their audiences through sheer numbers.

To its credit, “Honor Roll” forgoes the sensationalism of large casualty counts for the dull, ongoing ache of duration. Although the NewsHour couldn’t have known when the first segment aired, “Honor Roll” has evolved into the clearest depiction of what is most crucial about America’s current wars: their length. The continuous procession of fallen young men and women, now in it’s 11th year, signifies more deeply than any expert talking head, what a Long War actually means: the seemingly endless loss of life after life, day after day, month after month, year after year in ongoing military operations that have no clear ending and no objective criteria of success. Forget the fantasies of liberation peddled by our duly elected representatives and the scripts of positive change repeated ad infinitum by the generals: “Honor Roll” isn’t another war story, it’s a day-in day-out description of military occupation.

But in the grind of occupation, even the war-talk talking heads have disappeared, compounding the sense of alienation and waste. There’s something almost monstrously incongruous about watching 57 minutes of chatter about the Republican Party’s difficulties with Hispanic voters, the temperament of Washington, and the effect of sequestration on employment, only to be confronted with three final minutes of silent death. But that is who we have become. Chatter and death, week after week, chatter and death, month after month, chatter and death, year after year. In its own indirect fashion, “Honor Roll” goes about the dirty representational work of re-creating the current national character of the land of the free and the home of the brave.

“Honor Roll” isn’t easy. It takes determination to stay with the whole program and watch in silence as five or eight or twelve more young men and women scroll across your screen. And to complete the NewsHour’s representational proposition, you have to do this night after night after night. The 10+ year investment in time and effort is a testament to the NewsHour’s discipline and high regard for its viewers. It’s also devastating. One night doesn’t seem so bad, but then you remember the night before and then the week before and then the month before and then the year before. The cumulative effect feels like an almost unendurable loss. And in the midst of that unendurable loss, you can’t help but realize that there will be another night and another week and another month and another year (at least) to come. Facing that knowledge is enough to make you want to stop thinking about anything, but especially about the vast numbers of Iraqi casualties, the dead children, the drones. The only thing left to do is commit to watching another night, to honor the sacrifice another week, to mourn wounded families another month, to refuse to turn the channel for as many years as it takes.

Around and through and in spite of the nightly sorrow, there’s poetry in the photographs. Mostly official service portraits with a few snapshots, the photographs in “Honor Roll” reveal young men and women facing the camera willingly, aware that a photograph was in progress, actively shaping the formation of the image. These are not selves captured but selves imagined, selves committed to, selves feared for, selves forged through sacrifice and desire. In almost every case, the photographer has respected that imagined self, committing it to posterity without undue ostentation or artifice. There is in the social nature of this photographic engagement both trust and humility: trust on the part of the sitters and humility on the part of the photographers. Working together, through the simplest of photographs appearing at the very end of the nightly news, they remind us that human social relations can in fact be governed by mutual respect and dignity. It’s the slimmest glimmer of hope snatched from a media landscape both vast and depressing. But in my mind, that glimmer endures, resisting the chatter and death, denying the chatter and death, defining our loss not as body counts but as an ever-expanding communion of souls, haunting our living rooms and our future, repeating in a single voice, night after night, month after month, year after year: War is over.