Last week I gave a lecture to a couple of hundred students in Kansas. It was the first day back at school after Spring Break and the night before KU had won a big March Madness game. As the lights dimmed for my slideshow, I might as well have sung ‘rock-a-bye baby’ while I talked about Sleeping by the Mississippi. The twenty year olds were dropping like flies.

For most of the audience, attendance was mandatory. To prove they’d been there, each student had to hand in a short worksheet at the end of the lecture. I’d love to have read the sleepers’ comments. Better yet, I’d love to have seen their slideshows.

I thought about these sleeping students while reading Ali Smith’s Artful. The book is a transcription of four lectures Smith gave on European comparative literature at Oxford. While that might sound dull, the book reads like a passionate and unpretentiously intellectual dream.

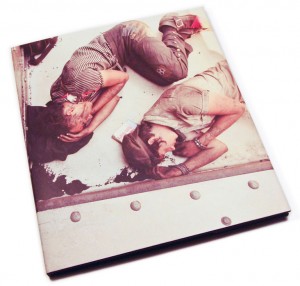

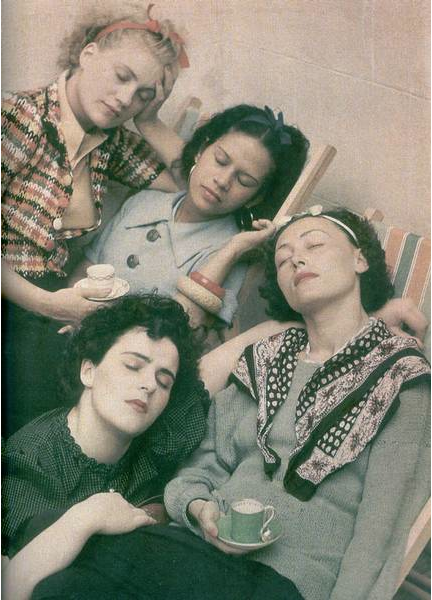

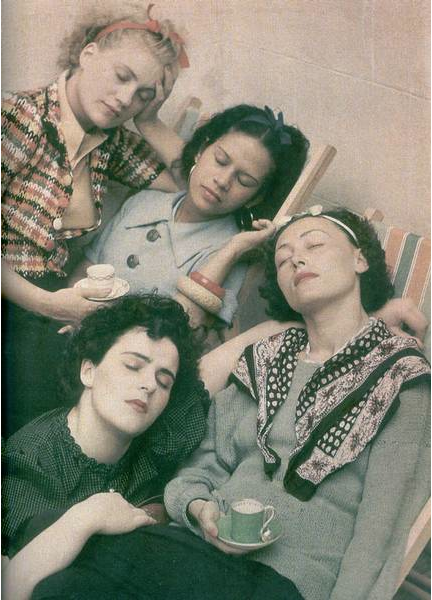

Here Smith writes about the photograph above while talking to the ghost of her fictional dead lover:

One day, quite late on, you showed me this photograph…You told me about how Lee Miller, the very beautiful woman at the top of the photograph, had started as a Surrealist photographer then in the Second World War had taken photographs all over Britain which still looked like they were Surrealism except now they were realism…

You told me how Miller’s photographs had been lost, completely forgotten about in the final decades of her life, while her husband, who’d taken the photo of the four sleeping women holding cups, Roland Penrose, carried on being the important figure he was in Surrealism and British art. Then one day, some time after her death, her son’s wife went up into the loft and found thousands of negatives, and a set of astonishing and vivid written dispatches she’s sent from the front to Vogue, who’d published them, in the war’s final push.

Then you’d pointed at the dark-haired woman sitting lowest in the picture. That’s Leonora Carrington, you said, one of the most underrated of the British Surrealist artist and writers…

That night in bed you showed me some of Carrington’s pictures. They were dark and bright, playful, like pictures from stories, but wilder, more savage, full of sociable-looking animals and wild-looking animals, beings who were part animal and part human, looking like they were all having a very interesting conversation, masked beings, people who were turning into birds or maybe it was birds turning into people…

You flicked further into the book and read me this: ‘However deeply we look into each other’s eyes a transparent wall divides us from explosion where the looks cross outside our bodies. If by some sage power I could capture that explosion, that mysterious area outside where the wolf and I are one, perhaps then the first door would open and reveal the chamber beyond.’

You told me Leonora Carrington was an expert in liminal space. What’s liminal space? I’d asked you. Ha, you’d said. It’s kind of in-between. A place we get transported to. Like when you look at a piece of art or listen to a piece of music and realize that for a while you’ve actually been somewhere else because you did? I’d said.

I confess that I nodded off while reading Artful during my flight home from Kansas, but Smith transported me as much as Delta. The slideshow I saw in my dreams was one of the best lectures I’ve never attended.

In last week’s post on Hologram For The King, I mentioned the importance of physically holding the book. This came to mind again with Artful. But in this case I wonder if the act of reading itself prevented me from fully plunging into Smith’s surrealist dream. In the lecture ‘On Edge,’ Smith writes:

Are words on the page more than surface? Is the act of reading something of a surface act? Do words on the page hold us on a surface, above depths and shallows like a layer of ice? (A book should be the axe to break the frozen sea inside us, Kafka says.) And what about reading on-screen – the latest, most modern way of communicating, working, writing a letter, writing a book, reading a book, telling a story?

What is a screen? A thing that divides. A thing people undress behind. A think every computer has, in fact a thing computing has distilled itself increasingly into…A thing that has an appearance of transparency and that divides us from bankers, ticket sellers, post office workers, people with money. A thing people project onto.

I’m jealous of the students that were able to attend Smith’s lectures. The attendance the first week was low. But then word got out that Smith was creating something artful and the audience tripled for the second lecture. By the final week there wasn’t an open seat in the house.

Reading Smith made me want to be more creative in the construction of my own lectures. There will always be sleepers, but I like the idea of the artist lecture being the launcher of dreams.