Fifteen years ago I was in an exhibition with my former teacher Joel Sternfeld. During the opening, the director of the gallery asked me to say a few words to the audience. But with public speaking at the top of my list of anxieties, no amount of pleading would get me to take the stage. “If you want to be an artist,” Joel said, “you are eventually going to have to deal with this.”

Initially this comment irritated me. The whole reason I’d become a photographer was that I liked working alone. But in time, I realized Joel was right. If you are in the art business, you are invariably asked to talk in front of an audience. So I eventually had to face my fear. It wasn’t always pretty, but the more lectures I gave, the more comfortable I became.

Recently I’ve been thinking about expanding the possibilities of the artist lecture. If art is about communication, why not try to be more artful in the construction of this form of communication – why not make the lecture its own form of art?

This was the fundamental question I had on my mind while organizing our recent Summer Camp for Socially Awkward Storytellers. As it turned out, the participants more than confirmed my belief in the artistic potential of this form. Their final presentations were emotional, funny and electric. Most of all, they made me think hard about how I can make my own lectures more vital.

One of the camp participants recently sent me a link to a lecture by the screenwriter Charlie Kaufman. It starts this way:

I’ve never delivered a speech before, which is why I decided to do this tonight. I wanted to do something that I don’t know how to do, and offer you the experience of watching someone fumble, because I think maybe that’s what art should offer. An opportunity to recognize our common humanity and vulnerability.

So rather than being up here pretending I’m an expert in anything, or presenting myself in a way that will reinforce the odd, ritualized lecturer-lecturee model, I’m just telling you off the bat that I don’t know anything. And if there’s one thing that characterizes my writing it’s that I always start from that realization and I do what I can to keep reminding myself of that during the process. I think we try to be experts because we’re scared; we don’t want to feel foolish or worthless; we want power because power is a great disguise.

With that, Kaufman begins a master class in socially-awkward storytelling. You can tell that Kaufman has invested himself totally in this talk. He’s thought long and hard about what he wants to say and why he wants to say it. And what he’s saying most fundamentally is this:

Say who you are, really say it in your life and in your work. Tell someone out there who is lost, someone not yet born, someone who won’t be born for 500 years. Your writing will be a record of your time. It can’t help but be that. But more importantly, if you’re honest about who you are, you’ll help that person be less lonely in their world because that person will recognize him or herself in you and that will give them hope. It’s done so for me and I have to keep rediscovering it. It has profound importance in my life. Give that to the world, rather than selling something to the world. Don’t allow yourself to be tricked into thinking that the way things are is the way the world must work and that in the end selling is what everyone must do. Try not to.

This is from E. E. Cummings: ‘To be nobody but yourself in a world which is doing its best night and day to make you everybody else means to fight the hardest battle which any human being can fight, and never stop fighting.’ The world needs you. It doesn’t need you at a party having read a book about how to appear smart at parties – these books exist, and they’re tempting – but resist falling into that trap. The world needs you at the party starting real conversations, saying, ‘I don’t know,’ and being kind.

This last note about being kind reminded me of another recent lecture – George Saunder’s commencement address at Syracuse University. While Saunder’s words aren’t as raw as Kaufman’s, I appreciated that rather than trying to be cool or smart, Saunders emphasized something “a little corny” : kindness.

It’s a little facile, maybe, and certainly hard to implement, but I’d say, as a goal in life, you could do worse than: Try to be kinder.

Now, the million-dollar question: What’s our problem? Why aren’t we kinder?

Here’s what I think:

Each of us is born with a series of built-in confusions that are probably somehow Darwinian. These are: (1) we’re central to the universe (that is, our personal story is the main and most interesting story, the only story, really); (2) we’re separate from the universe (there’s US and then, out there, all that other junk — dogs and swing-sets, and the State of Nebraska and low-hanging clouds and, you know, other people), and (3) we’re permanent (death is real, o.k., sure — for you, but not for me).

Now, we don’t really believe these things — intellectually we know better — but we believe them viscerally, and live by them, and they cause us to prioritize our own needs over the needs of others, even though what we really want, in our hearts, is to be less selfish, more aware of what’s actually happening in the present moment, more open, and more loving.

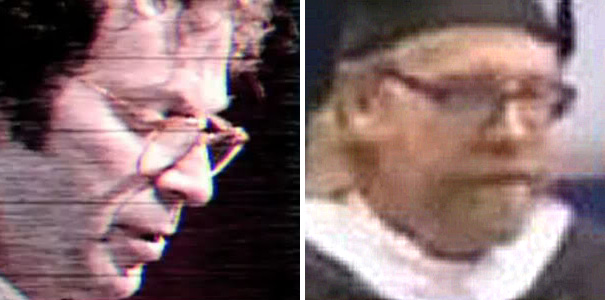

Listening to both Kaufman and Saunders was inspiring. Not only did they both make me want to give richer, more honest lectures – they both wanted me to be a kinder, more honest person. As grateful as I am for Being John Malkovich and 10th of December, I’m equally grateful for these lectures. I’m glad both writers were able to step away from the desk and talk directly to an audience.

George Saunders’s advice to graduates