During one of my lunchtime book search sessions I found the book, I love here now, by Maya de Forest. I decided to ask her a few questions.

Carrie Elizabeth Thompson: What sparked this project about your mother?

Maya de Forest: I was visiting Winnipeg about once a year and was becoming more aware of my mom’s physical aging year to year. At the same time she was becoming really active in the things that interested her like cooking and painting. At one point she was taking three flamenco dance classes a week, things of that nature. She was just so passionate about everything and it made me see her in this new light, like who is this person? These things all really prompted me to start taking photos of her. I then got an opportunity to move back home for a month in the middle of winter and decided to make a book project about her.

CET: Do you think of this as a project about your mother? Or is she a surrogate for aging women?

Maya: It could definitely act as a surrogate for aging women but I think it’s primarily about my mother’s own immigrant story and how that’s informed her identity as an aging person.

CET: There are a lot of images taken at night, is there something that happens to your mother at night that made you decide to use many night images?

Maya: It was more a process of what I thought was working sequentially and fit the overall tone of the book. Of course I was taking a lot of night shots at the time…there is something about snow at night that’s so beautifully quiet and kind of sad. I think the winter landscapes end up acting as kind of an existential backdrop to the whole thing. I suppose I was expressing my own feelings about her mortality as well as the hardships that I know she’s faced growing up in Japan during the war and making a life in a new country.

CET: How did you decide to add your mother’s writing?

Maya: I wanted to give the book some breathing room between sequenced photos initially. I like sequencing images in small groups and building those into a whole. The writing was originally very simple and secondary to break these sequences up, but I later realized that it could act as a

tool to really fill in the gaps of what the photos were not able to express. I ended up interviewing my mom at length and taking relevant text from there.

CET: Can you explain the title? When did your mother say this and what did you ask her to prompt this answer?

Maya: The title comes from her answer to my interview question “How do you feel about living in Winnipeg?” Her English has never been great but in the last 5 years her spoken English has deteriorated to the point where I now really struggle to understand her. She reads and

communicates with friends almost exclusively now in Japanese outside of talking with her immediate family, so, she’s very much immersed back into her culture. I used “I love here now” as the title because I think it both expresses and embodies her acceptance of these two worlds that

she lives in.

CET: Do you feel this project is complete, or will we see more images in the future?

Maya: The project to me is done, since its really documenting a very specific point in time in her life which doesn’t exist for her anymore. She just survived a major stroke last spring and it feels like she’s aged about 10 years overnight. I’ve been really taken aback by how rapidly people can age in their seventies, similar to how quickly people mature in their teen years. It’s fascinating, but its also hard to watch. I do still take photos though of my mother because she’s become such a great model. Maybe there’s a future project in there somewhere…

You can see more images here

Buy book here

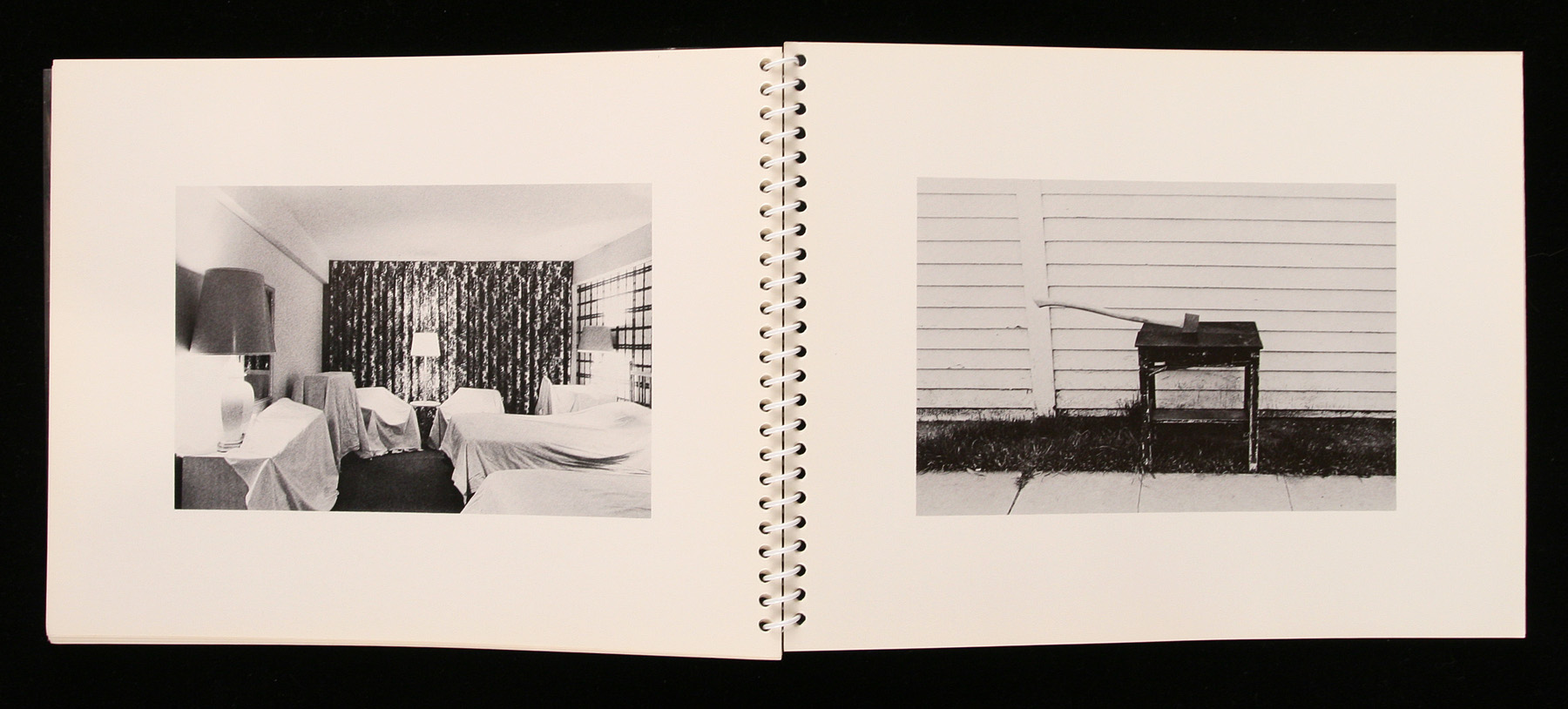

graphic design student, I recall wandering into the photography classroom. Sitting upon one of the long cardboard covered tables was a copy of ‘An American Visionary: Ralph Eugene Meatyard’. Simply out of curiosity or boredom I

graphic design student, I recall wandering into the photography classroom. Sitting upon one of the long cardboard covered tables was a copy of ‘An American Visionary: Ralph Eugene Meatyard’. Simply out of curiosity or boredom I