LBM Tote bags have arrived!

Screen Printed by our friends over at the lovely Faux Poco here in Minnesota.

100% Cotton Canvas

15 x 16 (Inches)

$8.00

Only a limited amount available. Get yours here!

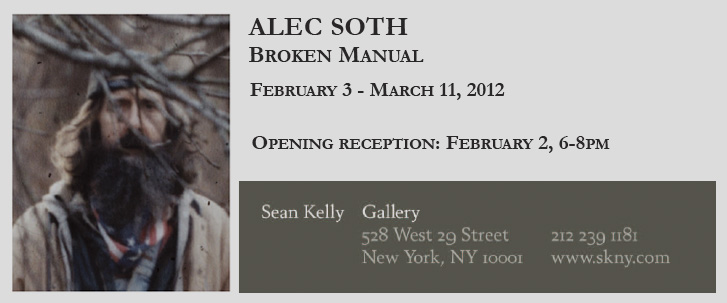

Sean Kelly Gallery is delighted to announce the opening of Alec Soth’s new exhibition, Broken Manual. The opening will take place on Thursday, February 2, from 6pm until 8pm. The artist will be present.

Last May, Paolo Pellegrin, Jim Goldberg, Susan Meiselas, Mikhael Subotzky, Ginger Strand and I drove an RV from San Antonio to Oakland. Since then, we’ve been trying to make something that expresses the frenetic energy of that trip. In the end, a simple book wouldn’t do. Instead we produced the Postcards From America box. Inside is a collection of objects – a book, five bumper stickers, a newspaper, two fold-outs, three cards, a poster and five zines, all in a signed and numbered box.

Designed by Emmet Byrne and Michael Aberman from the Walker Art Center, the result is, well, cooler than hell. Just check out this giant poster by Paolo Pellegrin:

Want to see more? Check out my video tour or go to the Postcards From America website.

The signed and number box (edition of 500) costs $250 from now until February 1st. Buy it here.

![]()

Here in Minnesota, where we usually spend the post-holidays buried in snow and bundling up against sub-zero temperatures, we experienced a lovely extended autumn that now seems to have skipped us ahead a few calendar months. The last week has felt like a perfect stretch of late March. We’ve been breaking high temperature marks all over the state. I’ve been nostalgic enough, in fact, that I’ve spent several nights hunting through photo books for some of my favorite winter images. Here are some that made the cut.

Vivian Maier, March 18, 1955, New York, NY.

Pentti Sammallahti, Solovki, White Sea, Russia, 1992.

Elin Høyland

Bruce Davidson, American Elms – The Mall in Central Park, 1994.

Emmet Gowin, View of Rennie Booher’s house. Danville, Virginia, 1973.

Nobuyoshi Araki, from (Sentimental Journey and Winter Journey, 1991)

I am excited to see the images Martin Parr makes in MN.

What are your favorite winter photographs? And is there any one photographer –or even several– that you particularly associate with the season?

In response to a recent post, I received an email from Cait who wrote:

“Like you, my partner shoots with a large format camera and makes treks around the country (and sometimes the world) for his work. He plans to keep this up for the long term. As we plan for our future, marriage and babies included, I can’t help but think about the challenges our partnership and family will face under somewhat fleeting and unpredictable circumstances. I would love to learn about you and your wife’s perspectives on this subject and/or be directed to any personal accounts or resources that you know of on the work-life balance of a photographic family.”

Kerstin Adams preparing a meal (1972) Robert Adams photographing (1984).

In thinking about how to reply to this, I first turned to Robert Adams. As regular readers know, I’ve been immersing myself in his work lately. In the new Adams retrospective book, The Place We Live, there is an essay by Jock Reynolds entitled ‘Taken Together’ on the importance of Kerstin Adams in Robert’s life and work. Reynolds paints a fairly remarkable picture of marital harmony:

“Robert began to suspect that he wanted to abandon teaching and become a photographer. Kerstin was characteristically encouraging, and when her employment schedule allowed it, she became his partner in the field. He did most of the driving and she cooked (on a little stove they called “Mother Svea”); at dusk he loaded film holders inside a homemade dark box in the back of their panel truck while she brushed away mosquitoes; in small towns she kept up diversionary conversations with curious onlookers so that he could compose upside down on the view camera’s ground glass; and each day they enjoyed together the sweep of the land and sky, and the privilege of being there.”

As is often the case when I think about Adams, I’m simultaneously impressed and discomfited. When I read about his life I feel like a carnivore reading the menu at a vegan restaurant.

So instead I turn to fellow carnivore Lee Friedlander and his wife Maria (I can’t imagine Adams eating peanut butter, tuna and cheese whiz on crackers!). Nobody has written more honestly about being the spouse of a photographer than Maria Friedlander.

Lee & Maria Friedlander 1968, 1997

On my old blog, I once quoted her powerful forward to a William Gedney book. Recently I came across Maria Friedlander’s introduction to her husband’s book Family:

“What is this Family Book? Is it our own family album? Is it our pictorial biography? Does this book tell us whether we are, to paraphrase Tolstoy in Anna Karenina, one of those happy families that are all alike or an unhappy family that is unhappy in its own way?”

She later writes:

“A book of pictures doesn’t tell the whole story, so as a biography this one is incomplete. There are no photographs of arguments and disagreements, of the times when we were rude, impatient, and insensitive parents, of frustration, of anger strong enough to consider dissolving the marriage. Lee’s camera couldn’t record our family dysfunctions. There are no photographs of Anna, Tom and Giancarlo during the three years in which they felt it would be better if they didn’t see us, and certainly no photographs of how Lee and I felt during that time. Tolstoy was right – when we’ve been an unhappy family we have been unhappy in our own way.”

Getting back to Cait and her concerns about marrying a photographer, I don’t think there is a good answer. Mixing marriage, kids, travel and artmaking is extremely challenging. It will sometimes be unhappy. “The challenge for artists is just as it is for everyone,” Robert Adams once said to a group of college students, “to face facts and somehow come up with a yes, to try for alchemy.”

![]()

Orson Wells by Eve Arnold. 1966

Orson Wells by Eve Arnold. 1966

A number of people have privately emailed me with concerns about all of the age talk on the blog lately. Am I depressed? Am I going to give up photography and buy a Ferrarri? The answer is no and no. I’m still happy with the minivan and I can’t remember being more comfortable with my age (mature and still regularly beating the 25 year-olds in ping-pong).

But yesterday I got a different email from a friend who works with Magnum:

“I just saw your and Martin’s equally depressing posts about being old. They reminded me of one of my favorite Guerilla Girls interventions – the list of advantages of being a woman artist (specifically number 4: “Knowing your career might pick up after you’re 80.”). So, you know, there might be a little White Boy Whining in all this.”

Knowing that I’m just stirring the pot, I’ve been able to brush off the criticism of my age posts. But this comment stung. Part of the reason it bothered me is that I’m vulnerable to similar accusations in other areas of my life.

At Little Brown Mushroom, for example, I publish a men’s magazine. I’ve defended this by pointing out that the magazine is actually about men and pokes fun at their longing. But the other day I received a copy of Jacques Magazine and was embarrassed to realize that whomever sent it probably did so because they thought it was similar to Lonely Boy Magazine.

And then there is Magnum. With today’s passing of Eve Arnold, we are now left with five living female photographers in the organization. It is beyond embarrassing.

So enough of my White Boy Whining. I’m happy to be 42. And I’m lucky as hell to have incredibly supportive women in my life. Beyond my wife (the most supportive and understanding person alive) I’m also lucky to have a fantastic studio manager, Carrie Thompson. The fact that Carrie manages to produce excellent photography while running my studio and supporting a child is mind-boggling.

So enough of the whining! Let me instead give thanks to women like Eve Arnold who manage to make great work when the odds, not to mention the culture, are so heavily stacked against them.

![]()

For my twenty-second birthday, my brother signed me up for a woodworking class. The classroom was in a suburban strip mall and all of the participants were men over sixty. While we whittled our first piece of wood, the instructor told us that the instruments were very sharp and we should be careful. Immediately after he said this, one of the men in the class nicked his finger. I secretly chuckled. Not a minute later I also cut myself. I clenched my finger and went to the bathroom. It was much worse than the other guy. Blood was spraying everywhere. I rushed out of the classroom and never returned.

Now that I’m twenty years older, maybe it is time to think about woodworking again. It seems to do wonders for some of the older artists I admire.

Robert Adams says: “It becomes mysteriously central and helpful to your health of spirit. It’s mainly just a wonderful way to relate to the world in another way. You can remember things in your hands and you can know things with your hands that you can’t know with your head.”

David Lynch says: “I really love wood, the texture of wood. I like to saw wood. In fact I love to saw wood. I like to put a saw against wood and cut the wood. I like the resistance, not too much resistance, just the right amount of resistance, and then the saw blade opens up some kind of fantastic smell that comes from the wood. It’s just a fantastic, beautiful experience.”

![]()

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iJnNZ-ysi80]

If Robert Adams represents one model for the aging photographer, this film by Weegee depicts a very different example.

![]()

A recent post by Blake Andrews on dead photoblogs has me thinking a lot about life online and off. From 2006 to 2007, I poured a lot of energy into my blog. On my first post, I wrote that I was ‘hungry for a bit of interaction with the world (albeit virtual).’ For my last post, I quoted Walt Whitman and his need to escape the astronomer’s lecture and go look at the stars.

A couple years later I started Little Brown Mushroom books. LBM is a publisher of physical objects, but like most businesses we support this with social media. But the LBM blog has never been like my old blog. The most effort I put into it is probably my year-end list of favorite photobooks. This year’s list of 20 books was a particularly big task to assemble. As a consequence I was eager to hear from readers. Did they disagree with my selections? What were their favorite books of the year? Happily, I got a lot of responses. A number of readers made me aware of books I hadn’t seen. And one commenter, John Gossage, tossed a couple follow-up questions back at me:

“Is there one book in your list that changed you as an artist? One of these that allowed you to take something from it that you could use to move forward?”

In the era where retweeting and ‘liking’ is the most interaction I normally expect online, Gossage’s question provoked me to go deeper. And so I did. I looked over my list and asked myself Gossage’s questions. The answers are complicated (several of the books changed me in incremental ways). But since this is a blog post, and not a conversation, I’ll try to keep it simple. The book that changed me the most this year was, in fact, not on my list:

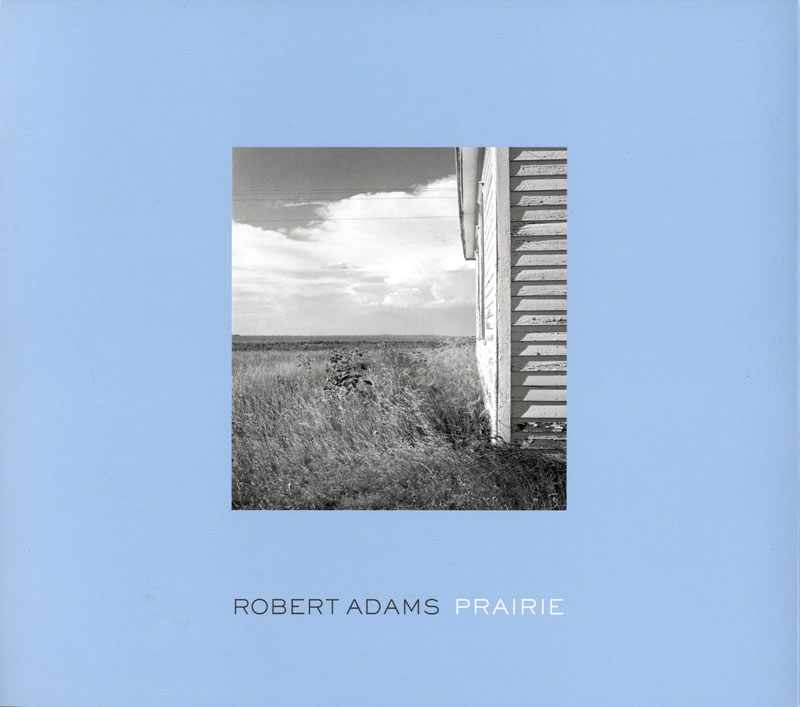

I often say that I understand Robert Adams a little bit more every year. Entering my 42ndyear , I guess I’ve been deepening this understanding for about 22 years. But I still keep learning. This year’s lesson came from the reprint of an Adam’s book from 1978: Prairie (2011, Denver Art Museum & Fraenkel Gallery).

I often say that I understand Robert Adams a little bit more every year. Entering my 42ndyear , I guess I’ve been deepening this understanding for about 22 years. But I still keep learning. This year’s lesson came from the reprint of an Adam’s book from 1978: Prairie (2011, Denver Art Museum & Fraenkel Gallery).

Prairie is a simple book. It is a small soft cover with minimal design flourishes. And Adam’s early pictures match the books humility. We see barns, farmhouses, an old church. Some of the pictures brush up against small-town photo cliché’s. The truth is that if Adams name weren’t on the book I’d probably never give it a chance. But this is an Adams book. And after 22 years I’ve learned that there is always more to learn from him.

As with most books by Adams, Prairie starts with a few well-chosen words by its author:

“Mystery in this landscape is a certainty, an eloquent one. There is everywhere silence – a silence in the thunder, in wind, in the call of doves, even a silence in the closing of a pickup door. If you are crossing the plains, leave the interstate and find a back road on which to walk; listen.”

The first picture is an utterly commonplace view of a gravel road and a telephone pole (this hardly looks like a mystery). The next two pages show an ordinary main street and then a closer-up picture of two kids in a pickup truck. (Still no mystery, bu I can hear the silence). Then, with this double-page spread, the real mystery begins:

Looking at these pictures, we immediately think of Walker Evans and his frontal cataloguing of country churches. At first it appears that the young Robert Adams is simply mimicking Evans and his famous depiction of two different small white churches in American Photographs (here and here). But a closer look at Prairie reveals that his photographs are describing the same church in two different seasons. It is as though Adams is acknowledging his predecessor while laying his own claim. For Evans, the churches are about rigorous, unromantic documentation. For Adams, the documentation of the churches is a way to explore the subtle mystery of weather and time.

On two more occasions in Prairie, Adams employs this use of repetition to quietly investigate time and perception:

What is most remarkable to me about this use of repetition is the fact that Adams was doing this in such a sophisticated way so early on. He later mastered this approach in Listening to the River (Aperture, 1994), but I find it encouraging that there were glimpses of it sixteen years earlier.

Another notable thing about Prairie is the inclusion of two pictures of Robert Adams’ wife Kerstin. This understated autobiographical content continues to separate him from more clinical strands of documentary photography. As with the use of repetition, it hints at work to come in books like Perfect Times, Perfect Places (Aperture, 1988).

All of this explains why I like Prairie. But I haven’t answered Gossage’s question about why the book offered me something that I could use to move forward as an artist. For me, Prairie brought home the fact that I need to sometimes look backward in order to move forward. I need to remember the reason why I first got interested in photography in order to continue photographing.

For Christmas my wife and I made handmade gifts for each other. Rachel made me beautiful ceramic tiles. I made her a book called One Mississippi Two. These were pictures made during a road trip along the Mississippi in 1992 (but not published in the book One Mississippi):

When a friend of ours saw this book the other day she said, “these look just like Alec’s pictures now. I don’t think I could tell the difference.” Of course I can tell the difference, but much of this has to do with technique. Otherwise the pictures are very much connected to those made twenty years later. In working to move forward as an artist, I think I would do well to make some of those connections to the past stronger.

So as the year comes to a close, I’m looking at my old photographs and Robert Adams books and thinking about time. In one of Adams’ books I keep a handwritten letter that he wrote to me in 2003 (after I sent him a copy of my maquette for Sleeping by the Mississippi). He ends his letter with this passage from the poem ‘I Sleep A Lot’ by Czeslaw Milosz.

I have read many books but

I don’t belive them.

When it hurts we return to

The banks of certain rivers.

Happy New Year,

![]()

Following up on my post on the age when photographers do their most influential work, I decided to look up the ages of the photographers who’d made the most influential books of the year (according to the EyeCurious tally of 52 year-end lists): Here are the top five:

Christian Patterson (39)

Rinko Kawauchi (39)

Yukichi Watabe (34 in 1958)

Ricardo Cases (40)

Valerio Spada (39)

Gregory Halpern (34)

Alex Webb (59) and Guido Guidi (70) tied for 7th place.

![]()

PS. Be sure to check out Martin Parr’s recent comment on the age discussion here