A couple of months ago I wrote about David Foster Wallace’s commencement address, This is Water. He begins his talk with the following story:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?

Wallace knows that it is a corny cliché to use a “parable-ish” story in a commencement address, but by the end of the talk, he brings the message home with real weight and seriousness:

The capital-T Truth is about life before death. It is about making it to 30, or maybe even 50, without wanting to shoot yourself in the head. It is about the real value of a real education, which has almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over:

“This is water.”

“This is water.”

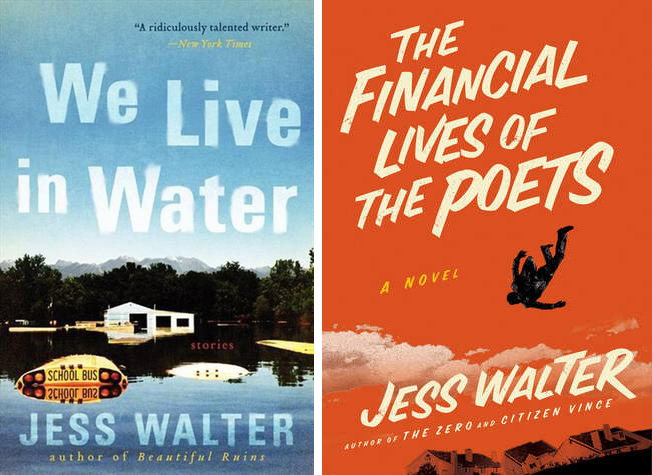

I couldn’t help thinking of Wallace’s parable when I picked up Jess Walter’s recently published collection of short stories, We Live in Water. At the beginning of the title story, a young boy repeatedly asks his father, “Do we live in water?” It is only at the end of the story that father understands his son’s question:

And there was the boy, staring into Flett’s giant aquarium, tropical fish swimming around in the blue light, a big square-headed whiskered thing probing the glass, and a skinny one with streaks of gold and a flitty little yellow one that darted in among the phony rocks. Michael was so close his nose almost touched the glass and his face was as blue as the fish, as he watched them swim the way he watched traffic out the window of Oren’s apartment, the way he looked at Oren in the car, the way he looked out at the world. And that’s when Oren understood.

Do we live in water?

He watched the fish come to the end of its blue world, invisible and impassible, turn, go around and turn again as he sensed another wall and another and on and on. It didn’t even look like water, so clear and blue. And the god-damn fish just swam in circles, as if he believed that, one of these times, the glass wouldn’t be there and he would just sail off, into the open.

As a collection of short stories, We Live in Water is like an aquarium. Each story describes a couple of fish, usually male, swimming in circles and smacking into the glass. I loved these stories, but was always disappointed when they ended. I wanted to watch one of Walter’s characters swim in a bigger tank.

So after finishing We Live in Water I picked up Walter’s 2009 novel, The Financial Lives of the Poets. It tells the story of Matthew Prior, a business reporter whose dream of quitting his newspaper job to start a website devoted to financial news told in poetic verse ends up leading to his family’s implosion. Reminiscent of Walter White in Breaking Bad, Matthew Prior’s desperate decision-making is pathetic, hysterical and wildly entertaining. It is also, as you might guess, poetic. Prior’s free verse is sprinkled throughout the story. As with his financial poetry, most of these poems are cheeky and intentionally average. But every now and then Walter slips in something serious. In a poem entitled ‘Dry Falls,’ Prior writes about the rural home along a dry riverbed that his father retreated to after leaving his mother.

And I wonder if we don’t live like water

seeking a level

a low bed

until one day we just go dry.

I wonder if a creek ever realizes

it has made its own grave.

Both We Live in Water and The Financial Lives of the Poets were enormously pleasurable to read. Along with being entertaining, they manage to lyrically address the ‘capital-T Truth’ of keeping your eyes open to the world hidden in plain sight.