A recent post by Blake Andrews on dead photoblogs has me thinking a lot about life online and off. From 2006 to 2007, I poured a lot of energy into my blog. On my first post, I wrote that I was ‘hungry for a bit of interaction with the world (albeit virtual).’ For my last post, I quoted Walt Whitman and his need to escape the astronomer’s lecture and go look at the stars.

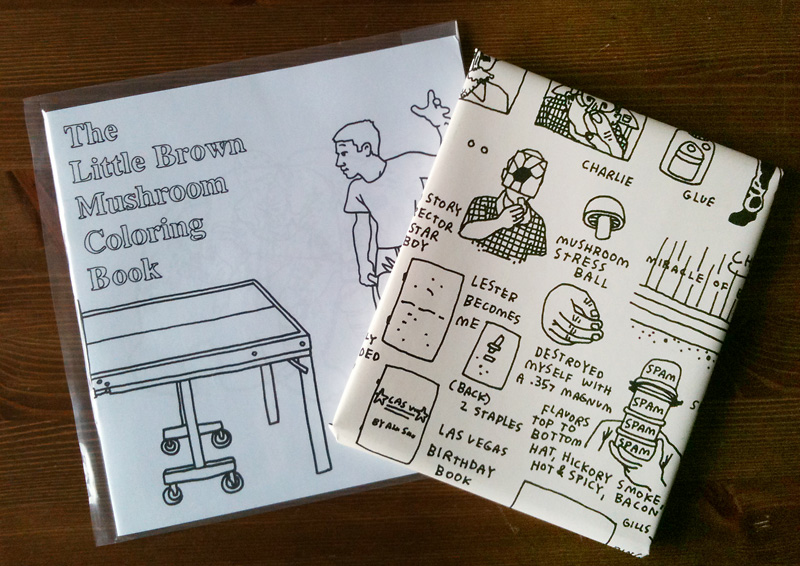

A couple years later I started Little Brown Mushroom books. LBM is a publisher of physical objects, but like most businesses we support this with social media. But the LBM blog has never been like my old blog. The most effort I put into it is probably my year-end list of favorite photobooks. This year’s list of 20 books was a particularly big task to assemble. As a consequence I was eager to hear from readers. Did they disagree with my selections? What were their favorite books of the year? Happily, I got a lot of responses. A number of readers made me aware of books I hadn’t seen. And one commenter, John Gossage, tossed a couple follow-up questions back at me:

“Is there one book in your list that changed you as an artist? One of these that allowed you to take something from it that you could use to move forward?”

In the era where retweeting and ‘liking’ is the most interaction I normally expect online, Gossage’s question provoked me to go deeper. And so I did. I looked over my list and asked myself Gossage’s questions. The answers are complicated (several of the books changed me in incremental ways). But since this is a blog post, and not a conversation, I’ll try to keep it simple. The book that changed me the most this year was, in fact, not on my list:

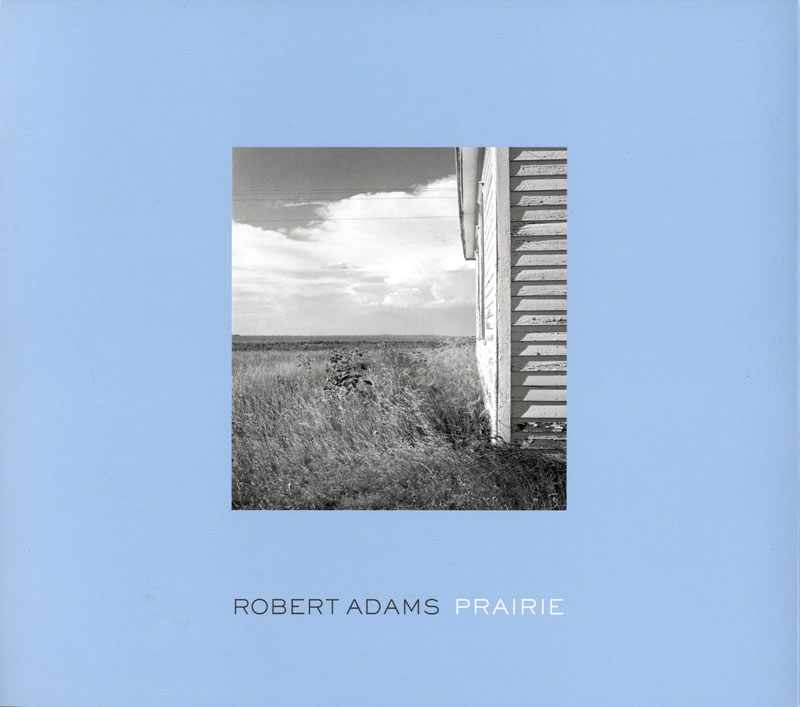

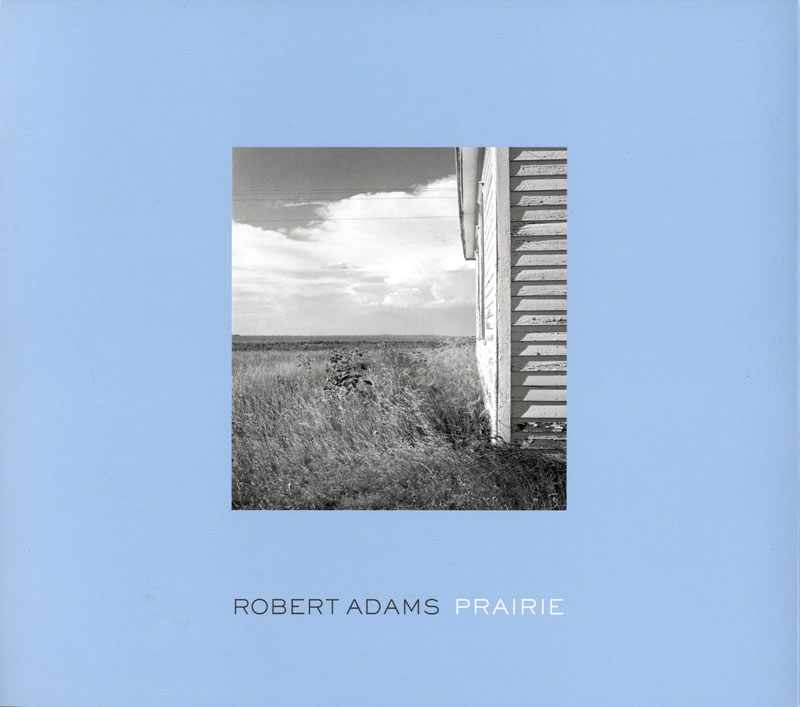

I often say that I understand Robert Adams a little bit more every year. Entering my 42ndyear , I guess I’ve been deepening this understanding for about 22 years. But I still keep learning. This year’s lesson came from the reprint of an Adam’s book from 1978: Prairie (2011, Denver Art Museum & Fraenkel Gallery).

I often say that I understand Robert Adams a little bit more every year. Entering my 42ndyear , I guess I’ve been deepening this understanding for about 22 years. But I still keep learning. This year’s lesson came from the reprint of an Adam’s book from 1978: Prairie (2011, Denver Art Museum & Fraenkel Gallery).

Prairie is a simple book. It is a small soft cover with minimal design flourishes. And Adam’s early pictures match the books humility. We see barns, farmhouses, an old church. Some of the pictures brush up against small-town photo cliché’s. The truth is that if Adams name weren’t on the book I’d probably never give it a chance. But this is an Adams book. And after 22 years I’ve learned that there is always more to learn from him.

As with most books by Adams, Prairie starts with a few well-chosen words by its author:

“Mystery in this landscape is a certainty, an eloquent one. There is everywhere silence – a silence in the thunder, in wind, in the call of doves, even a silence in the closing of a pickup door. If you are crossing the plains, leave the interstate and find a back road on which to walk; listen.”

The first picture is an utterly commonplace view of a gravel road and a telephone pole (this hardly looks like a mystery). The next two pages show an ordinary main street and then a closer-up picture of two kids in a pickup truck. (Still no mystery, bu I can hear the silence). Then, with this double-page spread, the real mystery begins:

Looking at these pictures, we immediately think of Walker Evans and his frontal cataloguing of country churches. At first it appears that the young Robert Adams is simply mimicking Evans and his famous depiction of two different small white churches in American Photographs (here and here). But a closer look at Prairie reveals that his photographs are describing the same church in two different seasons. It is as though Adams is acknowledging his predecessor while laying his own claim. For Evans, the churches are about rigorous, unromantic documentation. For Adams, the documentation of the churches is a way to explore the subtle mystery of weather and time.

On two more occasions in Prairie, Adams employs this use of repetition to quietly investigate time and perception:

What is most remarkable to me about this use of repetition is the fact that Adams was doing this in such a sophisticated way so early on. He later mastered this approach in Listening to the River (Aperture, 1994), but I find it encouraging that there were glimpses of it sixteen years earlier.

Another notable thing about Prairie is the inclusion of two pictures of Robert Adams’ wife Kerstin. This understated autobiographical content continues to separate him from more clinical strands of documentary photography. As with the use of repetition, it hints at work to come in books like Perfect Times, Perfect Places (Aperture, 1988).

All of this explains why I like Prairie. But I haven’t answered Gossage’s question about why the book offered me something that I could use to move forward as an artist. For me, Prairie brought home the fact that I need to sometimes look backward in order to move forward. I need to remember the reason why I first got interested in photography in order to continue photographing.

For Christmas my wife and I made handmade gifts for each other. Rachel made me beautiful ceramic tiles. I made her a book called One Mississippi Two. These were pictures made during a road trip along the Mississippi in 1992 (but not published in the book One Mississippi):

When a friend of ours saw this book the other day she said, “these look just like Alec’s pictures now. I don’t think I could tell the difference.” Of course I can tell the difference, but much of this has to do with technique. Otherwise the pictures are very much connected to those made twenty years later. In working to move forward as an artist, I think I would do well to make some of those connections to the past stronger.

So as the year comes to a close, I’m looking at my old photographs and Robert Adams books and thinking about time. In one of Adams’ books I keep a handwritten letter that he wrote to me in 2003 (after I sent him a copy of my maquette for Sleeping by the Mississippi). He ends his letter with this passage from the poem ‘I Sleep A Lot’ by Czeslaw Milosz.

I have read many books but

I don’t belive them.

When it hurts we return to

The banks of certain rivers.

Happy New Year,

Orson Wells by Eve Arnold. 1966

Orson Wells by Eve Arnold. 1966![]()

I often say that I understand Robert Adams a little bit more every year. Entering my 42ndyear , I guess I’ve been deepening this understanding for about 22 years. But I still keep learning. This year’s lesson came from the reprint of an Adam’s book from 1978: Prairie (2011, Denver Art Museum & Fraenkel Gallery).

I often say that I understand Robert Adams a little bit more every year. Entering my 42ndyear , I guess I’ve been deepening this understanding for about 22 years. But I still keep learning. This year’s lesson came from the reprint of an Adam’s book from 1978: Prairie (2011, Denver Art Museum & Fraenkel Gallery).