“Once when I was driving through Colorado with a friend, traveling down a narrow mountain pass, we came upon an accident. A pickup truck and a car had collided, and from fifty feet away we could see the blood. We pulled over and ran to help. All the time I was running, all the time I was trying, with my friend’s help, to pry open the door of the car in which a nine-months-pregnant woman had been impaled through the abdomen, I was thinking: I must remember this! I must remember my feelings! How would I describe this? I do not think I behaved less efficiently than my nonliterary friend, who was probably not thinking such thoughts; in fact, I may possibly have behaved more swiftly and efficiently, trying in my mind to create a noble scene. Nonetheless, what I felt above all was disgust at my mind’s detachment, its inhumane fascination with the precise way the blood pumped, the way flesh around a wound becomes instantly proud, that is, puffed up, and so on. I would have been glad at that moment to be a literary innocent.” – John Gardener, On Becoming A Novelist

If Adam Gordon, the poet-protagonist of the poet Ben Lerner’s first novel, Leaving the Atocha Station, were to encounter the grisly accident Gardner describes above, he wouldn’t use it as fodder for a novel. He’d probably just walk away from the scene and begin crafting a poem about his own creative listlessness compared to Gardener. Where Gardener laments the novelist’s detachment, in Leaving the Atocha Station, Lerner laments, and praises, the poet’s double-detachment.

On the third page of Leaving the Atocha Station, Gordon says: “Insofar as I was interested in the arts, I was interested in the disconnect between my experience of actual artworks and the claims made on their behalf; the closest I’d come to having a profound experience of art was probably the experience of this distance, a profound experience of the absence of profundity.”

The closest Gorden comes to a moment of true empathy during his time in Madrid is while instant messaging with his friend Cyrus in Mexico. Cyrus tells a gruesome story about a drowning that he and his girlfriend witnessed. But the focus of Cyrus’s story is the argument that this event created with his girlfriend.

Cyrus: She was shaken up in her way. She said she wished she’d never got in the water. But she also seemed excited. Like we had had a “real” experience.

Me: I guess you had

Cyrus: Yeah but I had this sense – this sense that the whole point of the trip for her – to Mexico – was for something like this, something this “real” to happen. I don’t really believe that, but I felt it, and I said something about how she had got some good material for her novel.

Me: is she writing a novel

Cyrus: Who knows

After finishing this remarkable novel, I read a dozen interviews with Ben Lerner. Like everybody else, I guess I was curious the extent to which Ben Lerner is Adam Gordon. My favorite interview was done by his friend Cyrus Console.

Cyrus: Adam Gordon…is always wondering if he’s capable of having a genuine experience of art. And yet the novel is full of Adam’s profound insights into the arts, especially poetry. I wonder if we could start by discussing this tension or complexity of Adam’s? It strikes me as central to the novel.

Ben: I think you’re right that it’s central. And I think the way a suspicion about and a commitment to the arts can coexist is one of the most interesting things about that domain of practices and experiences we think of as artistic. For the narrator of my novel, the issue isn’t just that there is bad art, or that there is a lot of bullshit in the arts, or bullshit artists, or that people pretend to be moved when they aren’t—what he’s trying to come to terms with is the fact that his interest in poetry, painting, etc., is largely grounded in the distance between the supposed potential of art and actual artworks.

Toward the end of the interview Console and Lerner discuss Lerner’s use of photographs in the book.

Cyrus: How does the novel’s use of images—I mean the photo- graphically reproduced images you’ve included in the book—relate to these concerns about mediation and spectacle?

Ben: One of the things that interests me about the use of images in a novel is how it complicates the prose’s relationship to what you could call “optical realism,” the way novelistic writing is often given the goal of dissolving itself into an image, a vision of a world. The claim of writing to make you see is interestingly strained, simultaneously restricted and enhanced, by the juxtaposition of prose with actual images, even ambiguous ones: the difference between reading and looking is more acutely felt.

But then Lerner goes on to discuss the unreliability of photography’s supposed “optical realism.”

Ben: There is an image that might be of Teresa, or somebody who looks like Teresa, but it’s a fragment, cropped so as to withhold the eyes, which the novel, as I mentioned, often, but never fully, describes—whatever “fully” would mean. And then there are captions that inflect how we view the images, so that they end up illustrating the problematic nature of the illustrative as much as actually anchoring the prose in a visually intelligible world.

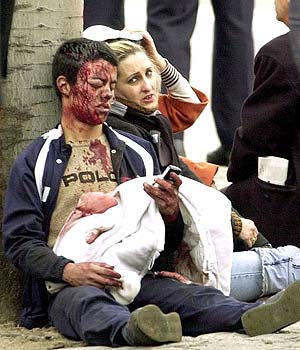

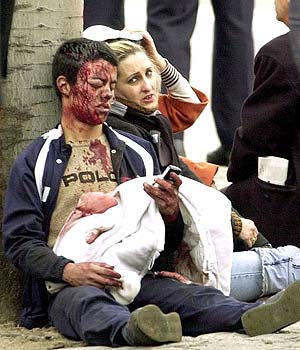

After reading this, I decided to do a Google Image Search on Atocha Station bombings. This is one of the first images I found:

I’ve spent a lot of time looking at this picture and have a bunch of questions:

- Is the man holding a baby or a jacket? Does it matter?

- Why is the blood so perfectly covering one side of the man’s face? If the other side were shown, how would it change the picture?

- Is the woman looking at the photographer, the bloody man, or somewhere else?

- How is the photographer’s sense of engagement or detachment different from that of the novelist or poet?

Answer: Who knows

Photography, it seems to me, has as hard of a time dealing with the real as novels or poetry. And if the picture above isn’t good enough at “illustrating the problematic nature of the illustrative,” look at the way this picture of Atocha Station was reproduced in two British newspapers:

After looking at these pictures, I decided to track down the John Ashbery poem “Leaving the Atocha Station” from his 1962 book, The Tennis Court Oath. An excerpt:

Leaving the Atocha Station steel

infected bumps the screws

everywhere wells

abolished top ill-lit

scarecrow falls Time, progress and good sense

strike of shopkeepers dark blood

I also read the book’s title poem and was struck by the first two lines: What had you been thinking about / the face studiously bloodied

This brought me to a final question/joke/koan: A poet, a novelist and a photographer leave Atocha station after the massacre – which one sees the event more truthfully?

Answer: His girlfriend