I’m embarrassed that my work relies so much on travel. Not only is it bad for the environment, I’m not sure it’s good for the soul. Artists who sustain Morandi-like mindfulness to their immediate surroundings are like chefs sautéing vegetables from their garden while I eat at a strip-mall Applebees.

“Shelter from home” is an opportunity for me to change all of that. Privileged enough to have a safe house and yard, I should be baking bread, scattering it in a freshly planted garden and photographing the visiting wildlife. But instead I’m inside watching Tiger King and eating frozen pizza. I’ve barely been able to assemble this newsletter, much less make serious work. I console myself by reading articles with titles like “Why You Should Ignore All That Coronavirus-Inspired Productivity Pressure.” I found this snippet from a recent essay by Rebecca Solnit particularly helpful:

“As the pandemic upended our lives, people around me worried that they were having trouble focusing and being productive. It was, I suspected, because we were all doing other, more important work. When you’re recovering from an illness, pregnant or young and undergoing a growth spurt, you’re working all the time, especially when it appears you’re doing nothing.”

Even though I’m not able to make work at my house, I’ve been comforted by looking at other people’s homes, particularly when rendered with unvarnished artistry. A well-seen depiction of someone else’s overgrown garden allows me to see my own with affection.

In this newsletter:

- Picture & Poem: “The Cabbage” by Ruth Stone

- Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: “Keeping Vigil”

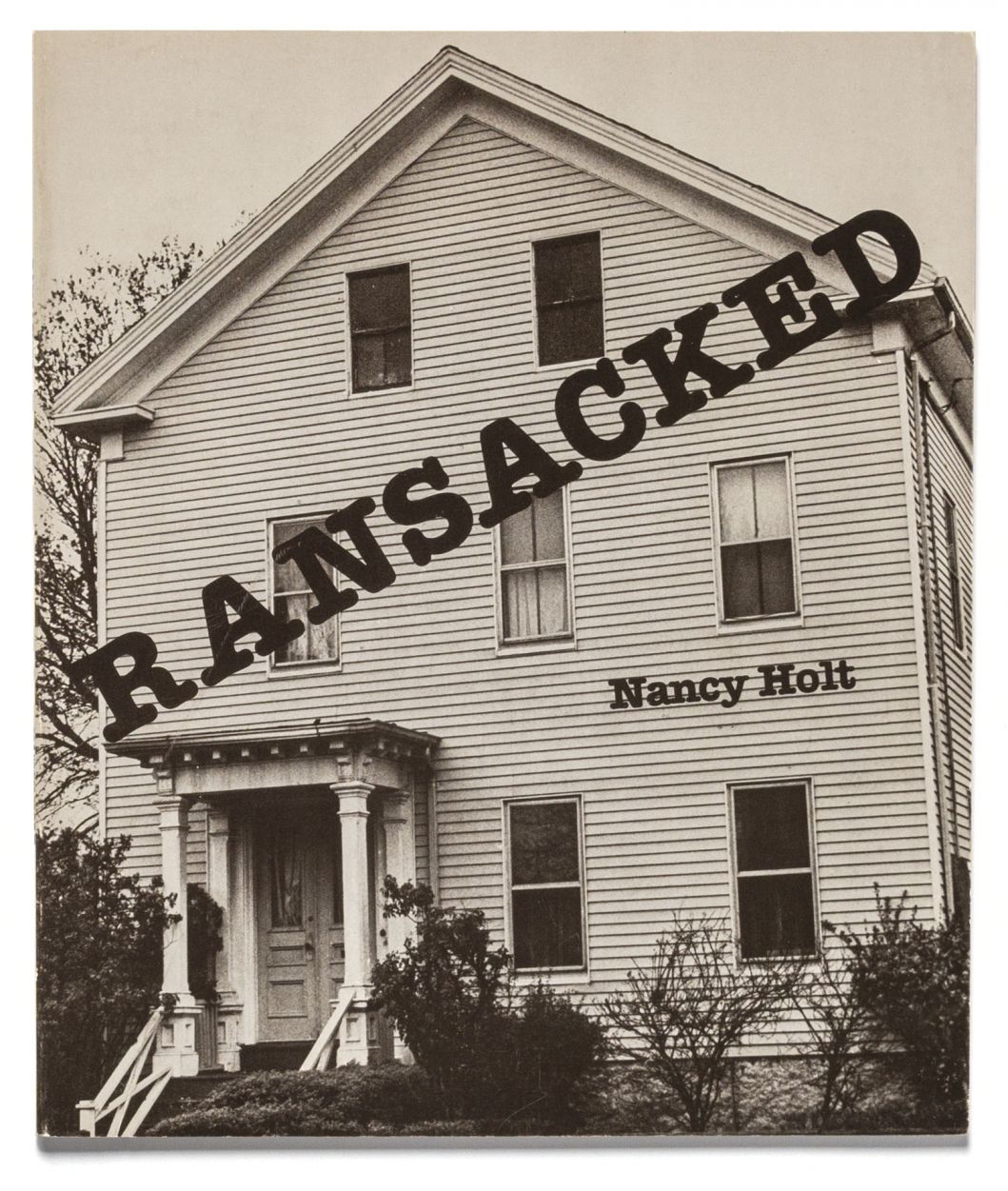

- Ex-Libris: Ransacked by Nancy Holt

- Recently Received: Pleasant Street by Judith Black

- The Lunch Table

Picture & Poem: The Cabbage by Ruth Stone

After receiving a poetry prize in 1956, Ruth Stone and her second husband Walter purchased a 19th-century farmhouse in rural Vermont. When Walter committed suicide two years later, Stone was left to raise her three daughters alone. She survived by becoming an itinerant professor. “She often rented apartments for the teaching semesters, or when the winters were too harsh for her to live alone in her house in the mountains,” her granddaughter (the exceptional poet) Bianca Stone wrote to me.

I admire the poems Ruth Stone wrote while away from home. In one entitled “One Year I Lived in Earlsville, Virginia,” she writes about living in the home of another poet who had gone to New York for a year. “I lived with his cats and his furniture and his books and his sorrow. Sorrow was everywhere.” Sorrow is everywhere in Stone’s poetry, but so is mystery and enchantment. Her poem from Earlsville ends “Those endless closets and halls in the brain where the unknown hides; that open for a moment and close again. That is where the poems come from.”

When I read Stone’s poetry, I picture an imaginary home that is a combination of her Vermont farmhouse, the rented apartments, and a vast mansion of the imagination. “Her house is made of poetry,” the literary critic Sandra Gilbert wrote, “her intense attention to the ordinary transforms it into (or reveals it as) the extraordinary.”

No poem better exemplifies this than “The Cabbage.” The painting in the poem is by her daughter Phoebe. “She often would write a poem about one of my paintings,” Phoebe said to me, “Sometimes she would write it on an old envelope and later she would type it up. My mother liked to be around her family when she wrote. She liked hearing our voices in the next room.”

The Cabbage

by Ruth Stone

You have rented an apartment.

You come to this enclosure with physical relief,

your heavy body climbing the stairs in the dark,

the hall bulb burned out, the landlord

of Greek extraction and possibly a fatalist.

In the apartment leaning against one wall,

your daughter's painting of a large frilled cabbage

against a dark sky with pinpoints of stars.

The eager vegetable, opening itself

as if to eat the air, or speak in cabbage

language of the meanings within meanings;

while the points of stars hide their massive

violence in the dark upper half of the painting.

You can live with this.

Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: Keeping Vigil

It had been twenty-nine days, or thirty-one, or forty, or who knows, since any human contact IRL. Merriam-Webster posted a list online of forgotten words that no longer feel obsolete. Solivigant, a solitary wanderer. Scripturient, having a strong urge to write. Flingee, one at whom anything is flung.

People started talking about drive-in movie theaters again, the pretend togetherness of a wide-open space and a shared screen, tucked inside the windowed bubble of your car or stretched out on the island of a blanket in a dirt field. A friend texted about the time his grandmother took him to the drive-in to see Dolly Parton in Rhinestone. I missed out on all that early on, I told him; the drive-in near my hometown had closed in the seventies. By the middle of March, I thought how I would far prefer to teach in a drive-in classroom, instead of Zooming to my students, now shrunken to groups of sixteen and eighteen little squares on a laptop screen. I’d get a microphone, I swore; a megaphone; a PA. The last time I saw them we were in university fluorescent light, the one thing we will eventually agree none of us miss.

Outside, through humid, fogged windows, is a guilty, lucky landscape: the irony of a tide of hermit crabs arriving on a government-emptied beach. Inside is the motel efficiency that I rented in January, temporary quarters for a visiting professorship. The last time I returned home to New York, at the beginning of March, I set out a box of gloves, disinfectant wipes, hand sanitizer, like you might a bowl of fruit. I took a train to Virginia to finish the semester when that idea still held some logic, feeling like a time traveler from a future no one was prepared to believe.

Outside, the deserted beach still wears the look and the cold of the off-season, storm-green skies over a hammered silver surface, city trucks diligently paving the sand. Inside, the daily tornado. By night, my room is littered with notebooks and false-start paragraphs, sentences that start strong and fall, suddenly, off the edge of a cliff. At the end of the day I pick them up and stack them into piles as if that would cause them to reassemble overnight into something that makes sense. Then I stack them mentally against the stories of others— the cruelties and the sacrifices, the workers inside the hospital two blocks from my place in Brooklyn, the hospitals all over the city— and they crumble.

I tell my students to go easy on themselves now. That the sleeplessness is part of our job now. How wakefulness forces us to sit with our sadness and our fear and our fury. How it becomes our job to hold vigil for those who aren’t allowed to rest and for those who died alone and for those who mourn alone. We read aloud from Svetlana Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl— I’d assigned it months ago and now it shows up on our syllabus with eerie echo. It is on us now to pay attention, to read, to listen, to watch, to feel. Write, I say, but throw it in a drawer. Let your thoughts accumulate but hang on to them, shaky as you feel, as long as you’re lucky enough to stay inside a room that will hold them.

My students are in their 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s. They are, some of them, essential workers who are required to physically report to work, they are getting laid off or furloughed, they have loved ones with threatening health conditions, they are homeschooling their children, they are worried for significant others and family miles and many states and many countries away. They defend their MFA theses over Zoom. For some, the classroom is not only virtual but, amid new and bewildering and mounting pressures, totally unreal. School, one student tells me, feels so faraway now, like a US Weekly article about some star-studded divorce.

I tell them if you can’t make anything up, if you can’t think straight, it’s enough to get down the details. (John Prine, once: “The day when you get your heart broken, you have all the time in the world to write about it: how it feels, what the temperature was that day.”) Record the things you’ll forget, that your brain will later shield from you the way trauma erases and reshapes memory. Your last night out in the world. The last time things seemed normal. The morning the grocery store first felt dangerous. The first moment it all felt close to home. The room where you are isolating now. They write of curling up to read on discarded sofas, the solitary reassurance of driving, surreal last meals in strip malls.

Speaking of Prine, write how, in the space of a week we lost two of our finest balladeers, everyday people, Army and Navy veterans, alchemists of grief descended from coal miners and beer can factory employees. Lean on me; use me. Bill Withers writing “Ain’t No Sunshine” as he stood on the job fixing airplanes. Prine, the Singing Mailman, stitching together sadness and jokes and rambling tales into lyrics he thought up on his letter carrier routes decades before the U.S. Postal Service is threatened with becoming a near casualty too. Make me an angel that flies from Montgomery/ Make me a poster of an old rodeo/ Just give me one thing that I can hold on to/ To believe in this living is just a hard way to go.

When I can’t work, I screenshot the stories I’m reading to remember them in context, the online ads that populate them. Closing lines by Peter Schjeldahl, writing about the experience of standing in front of Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas at the Prado, are now forever auto-illustrated for me by the arrangement of generic-brand hand sanitizer and a digital thermometer that appear, courtesy of the internet, alongside this passage:

It’s not like going back to anything. It’s like finding yourself anticipated as an incidental upshot of fully realized, unchanging truths. The impression passes quickly, but it leaves a mark that’s indistinguishable from a wound. Here’s a prediction of our experience when we are again free to wander museums: Everything in them will be other than what we remember. The objects won’t have altered, but we will have, in some ratio of good and ill. The casualties of the coronavirus will accompany us spectrally. Until, inevitably, we begin to forget, for a while we will have been reminded of our oneness throughout the world and across time with all the living and the dead.

When the sentences have no logic, I tell my students, set the two halves that don’t fit next to each other anyway.

I am scripturient. I cannot think straight.

There’s a man on the motel lawn in flag shorts and a tank top that reads MANDATORY FUN; we’re in the midst of a pandemic.

Camellias and dogwoods and azaleas are blooming; in New York, now more than 10,000 gone.

Write how, on the seventeenth night or maybe it was the twenty-seventh, you had stopped scrolling and watched pirated Northern Exposure on a friend’s shared screen Zoom, blurry and subtitled in Czech. Sám jako kámen na světě, Ed said. Alone like a stone in the new world. (A solivagant, I think.) A lyric that belongs to Withers, that belongs to Prine.

*

Recently I came across a story of a Spanish flu survivor from a county bordering the rural county in North Carolina where half my family is from. “That was the roughest time ever. Like I say, people would come up and look in your window and holler and see if you was still alive, is about all,” remembered a man whose first name was Glenn and whose last name happened to be Holler. “They wouldn’t come in.”

In the years after my own great-grandfather died, my relatives brought out a box of his diaries and took turns reading them aloud. There were no bombshells, no juicy gossip, just the gruff and droll and dutiful record-keepings of a father of ten children in a small town in North Carolina who served for many years as the county sheriff. Very occasionally there were glimmers of local crime, but mostly: babies born, snow and rain, the weather that day, a farmer’s almanac in reverse. I don’t know how far those journals went back but I think now how it wouldn’t be such a bad thing to read one ordinary person’s diary of the weather in 1918. What the temperature was that day. How many inches of rain fell.

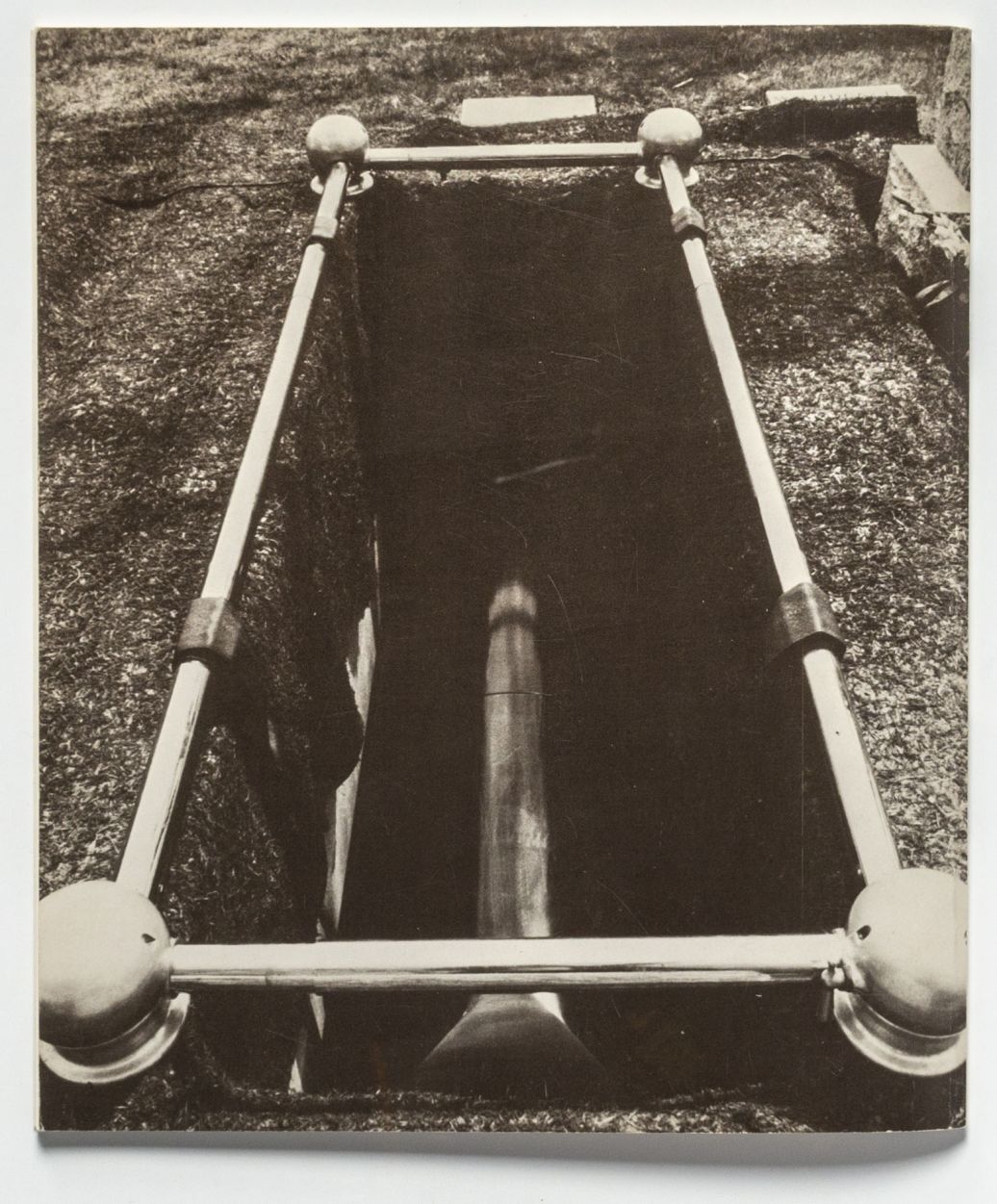

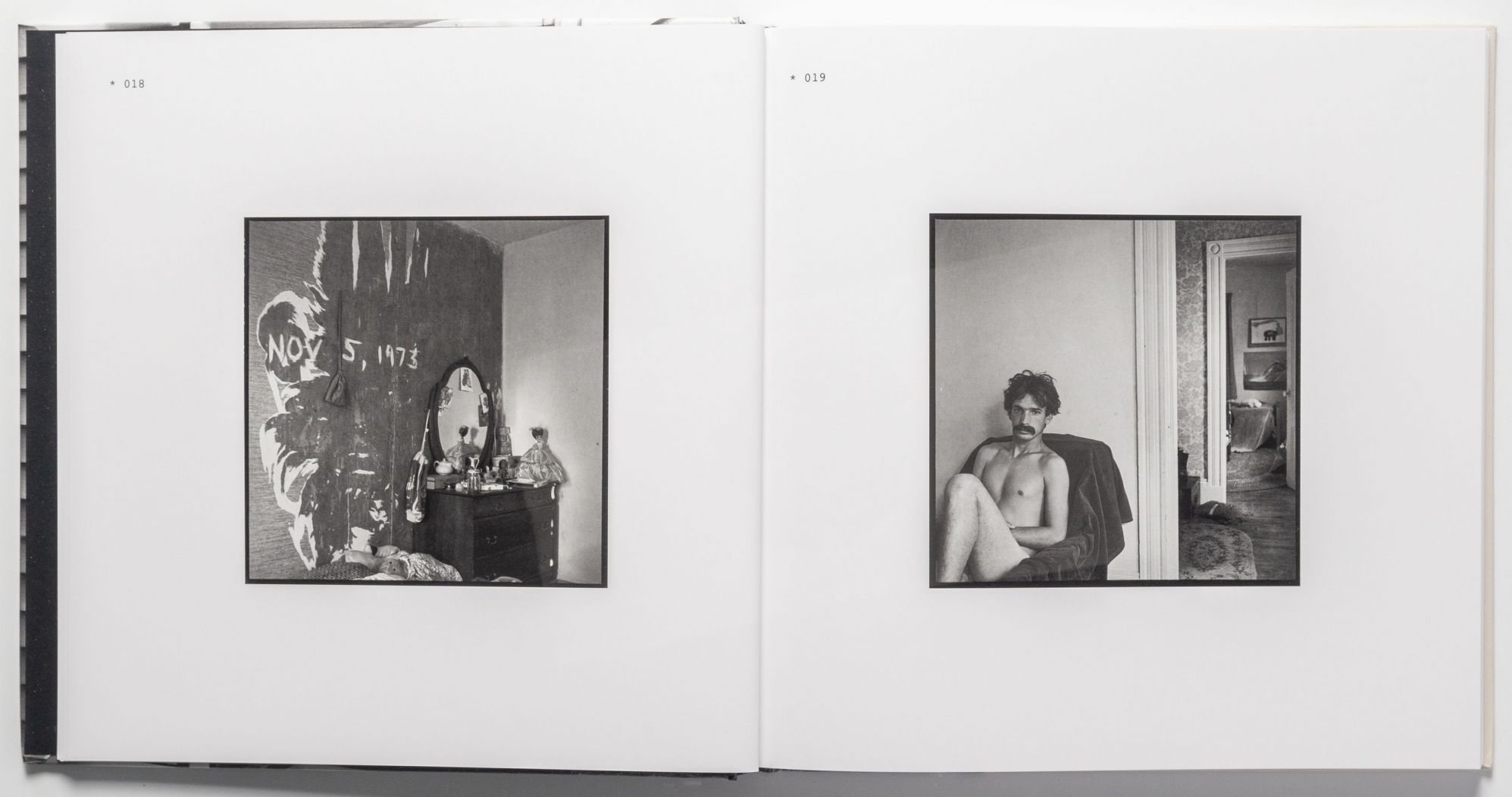

Ex-Libris: Ransacked by Nancy Holt

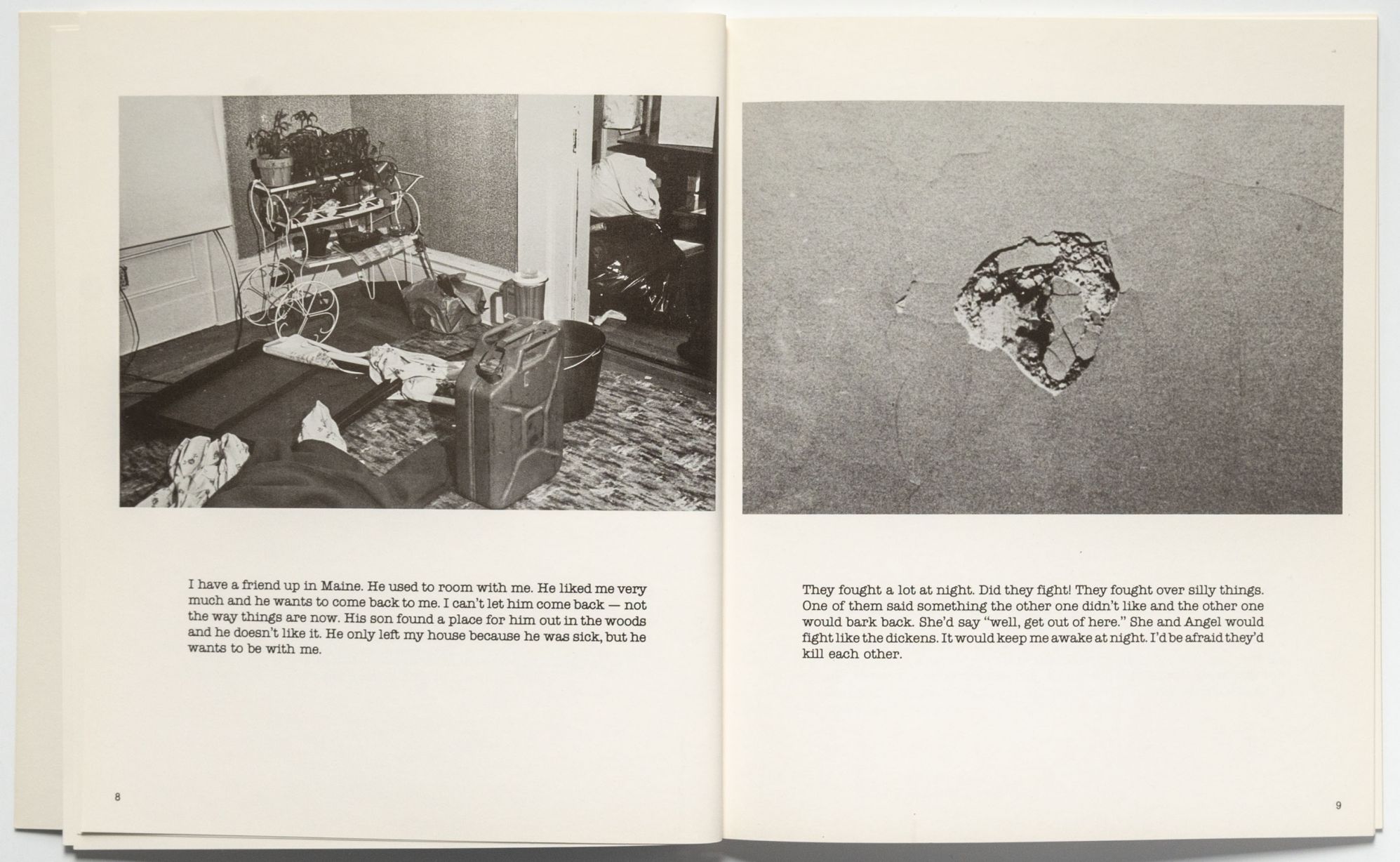

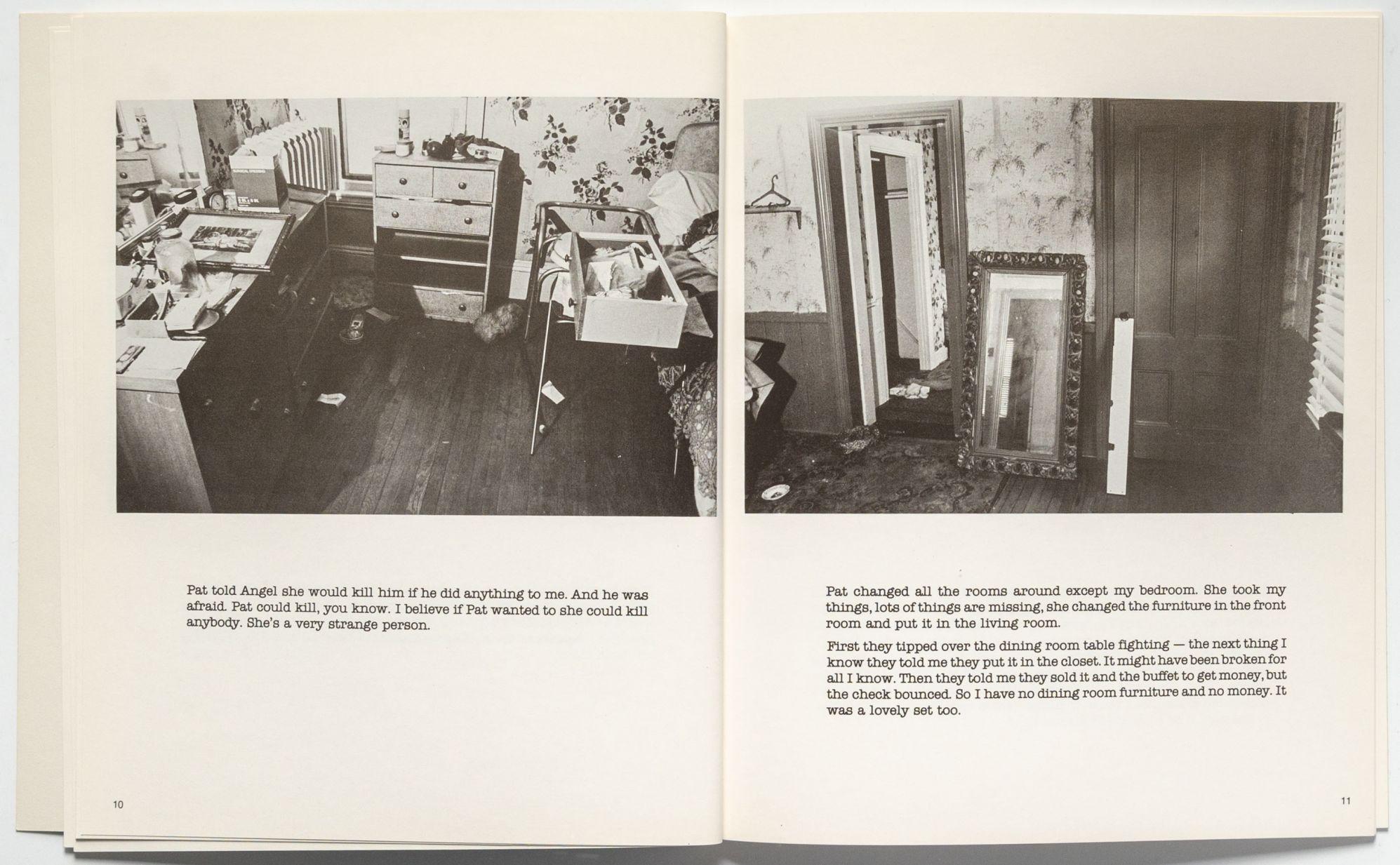

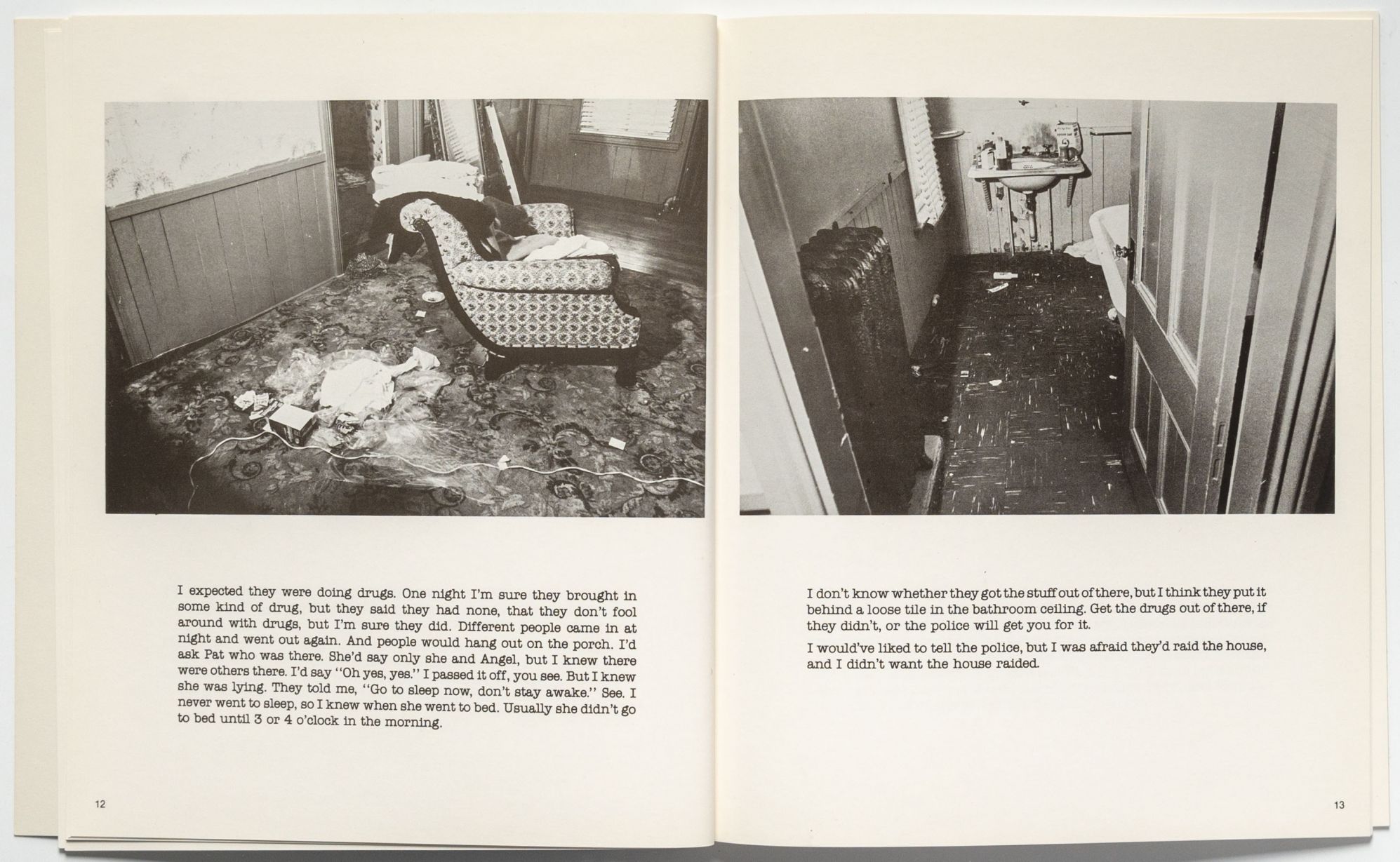

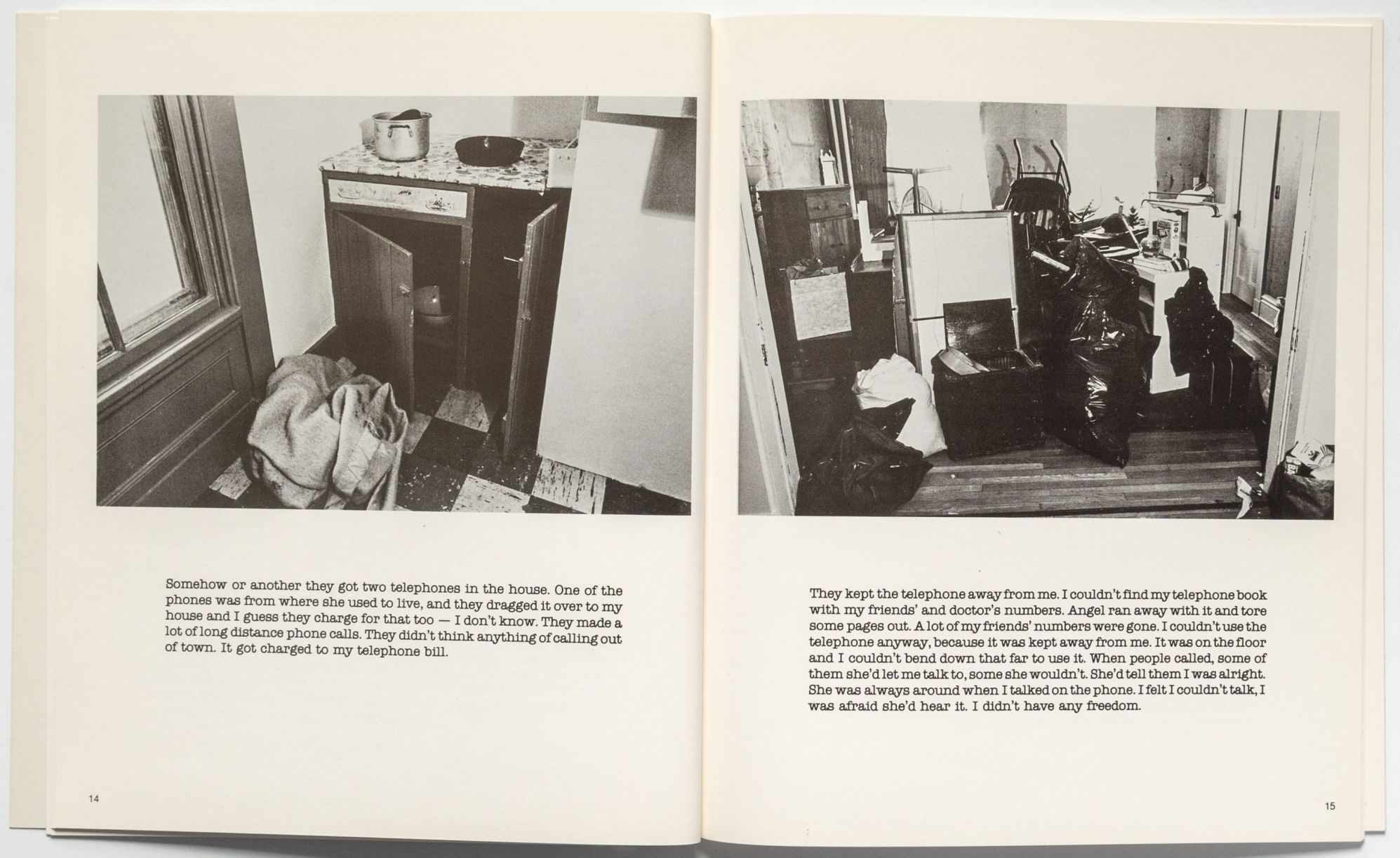

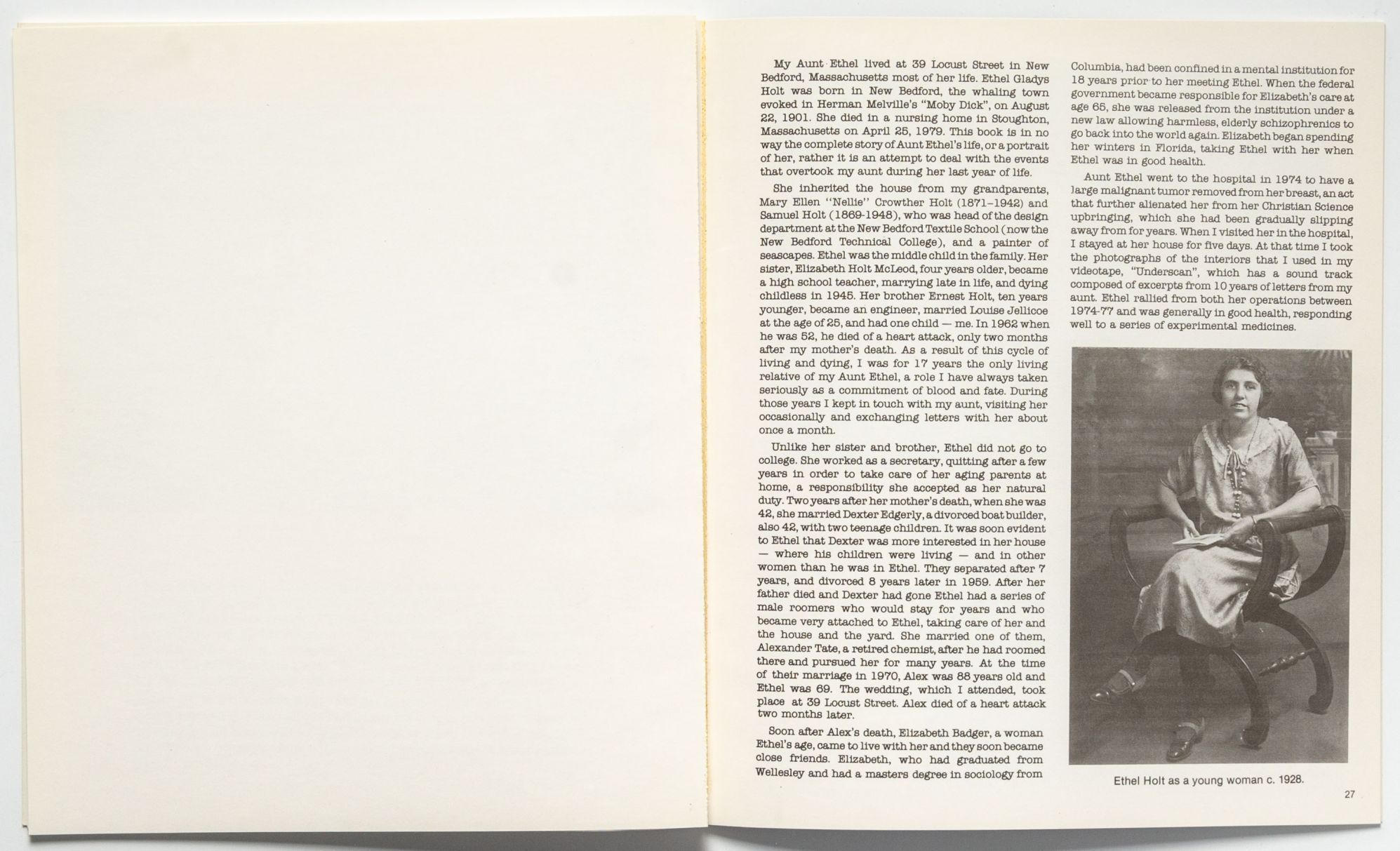

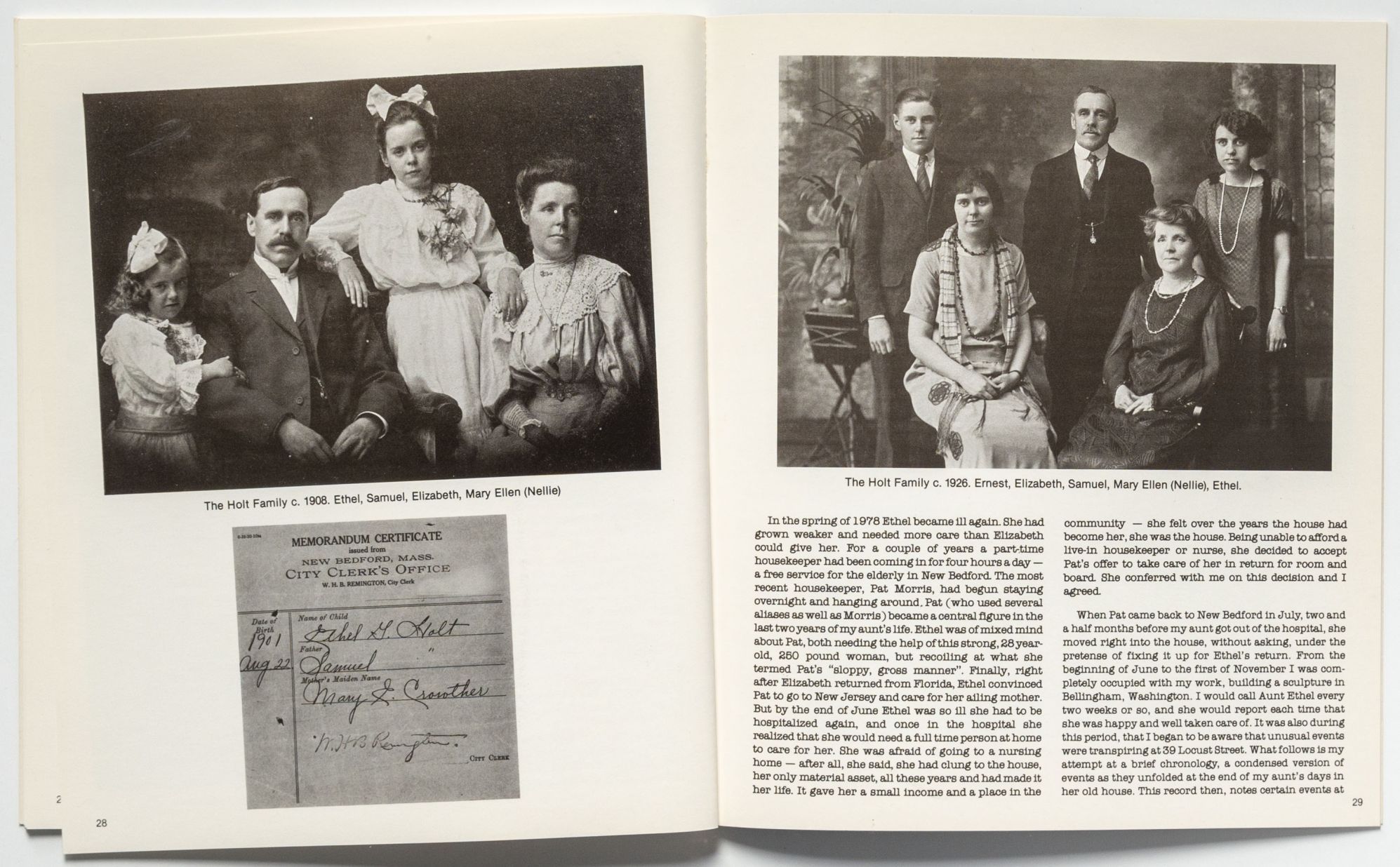

Why on earth would I post a book about elder abuse and crushing loneliness during a time like this? I don’t have a good answer. But the fact that I keep returning to this harrowing book must have some sort of meaning.

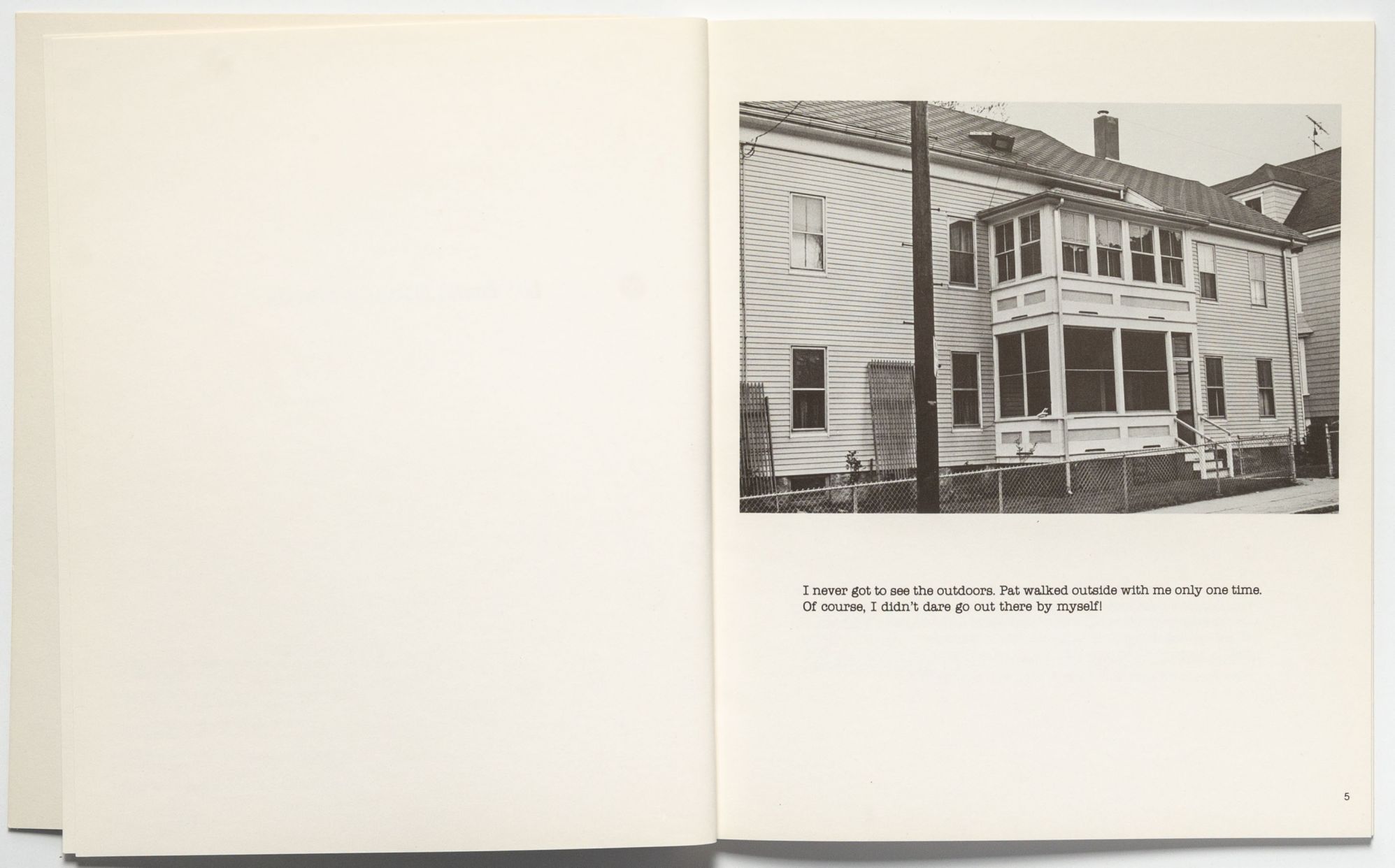

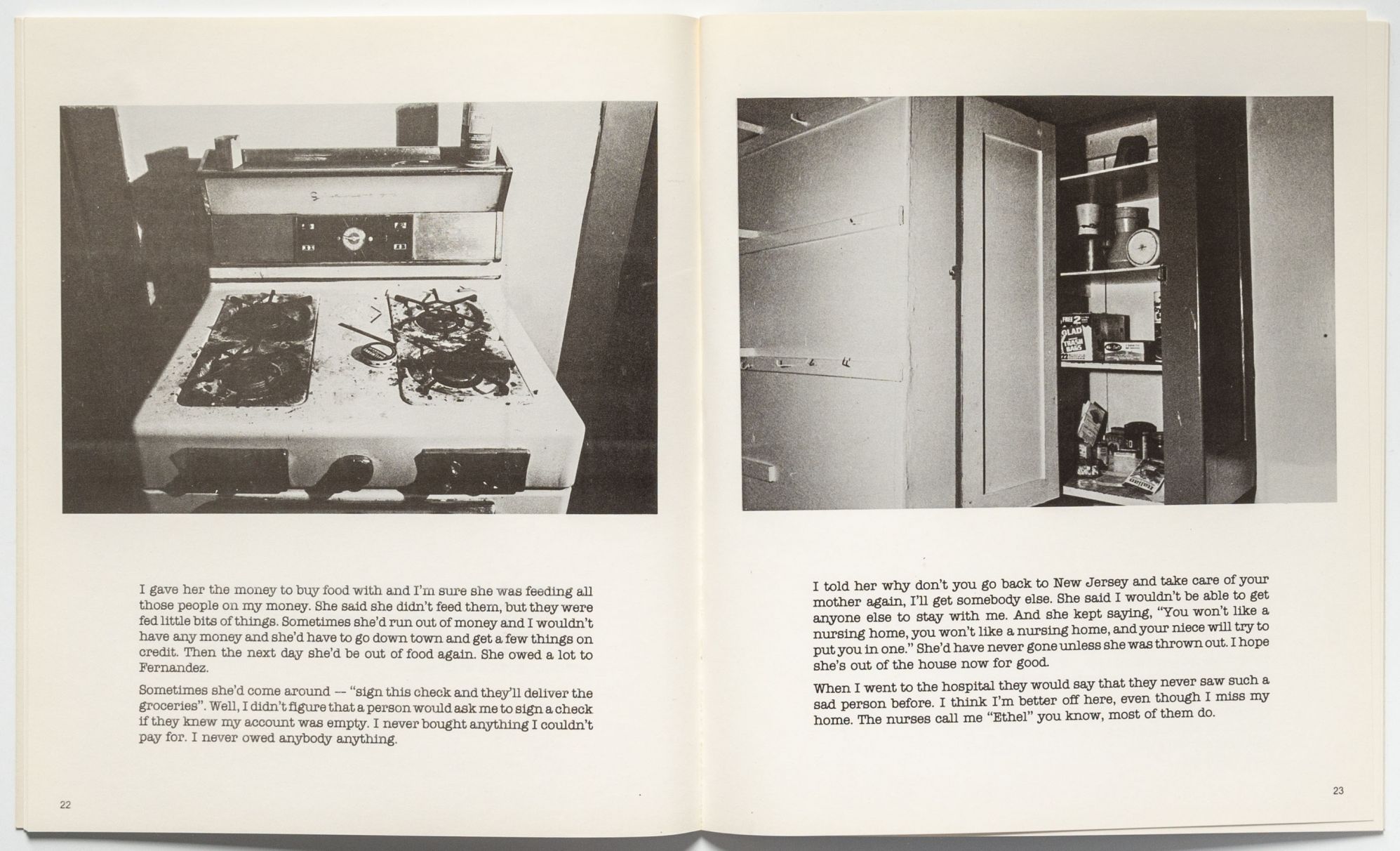

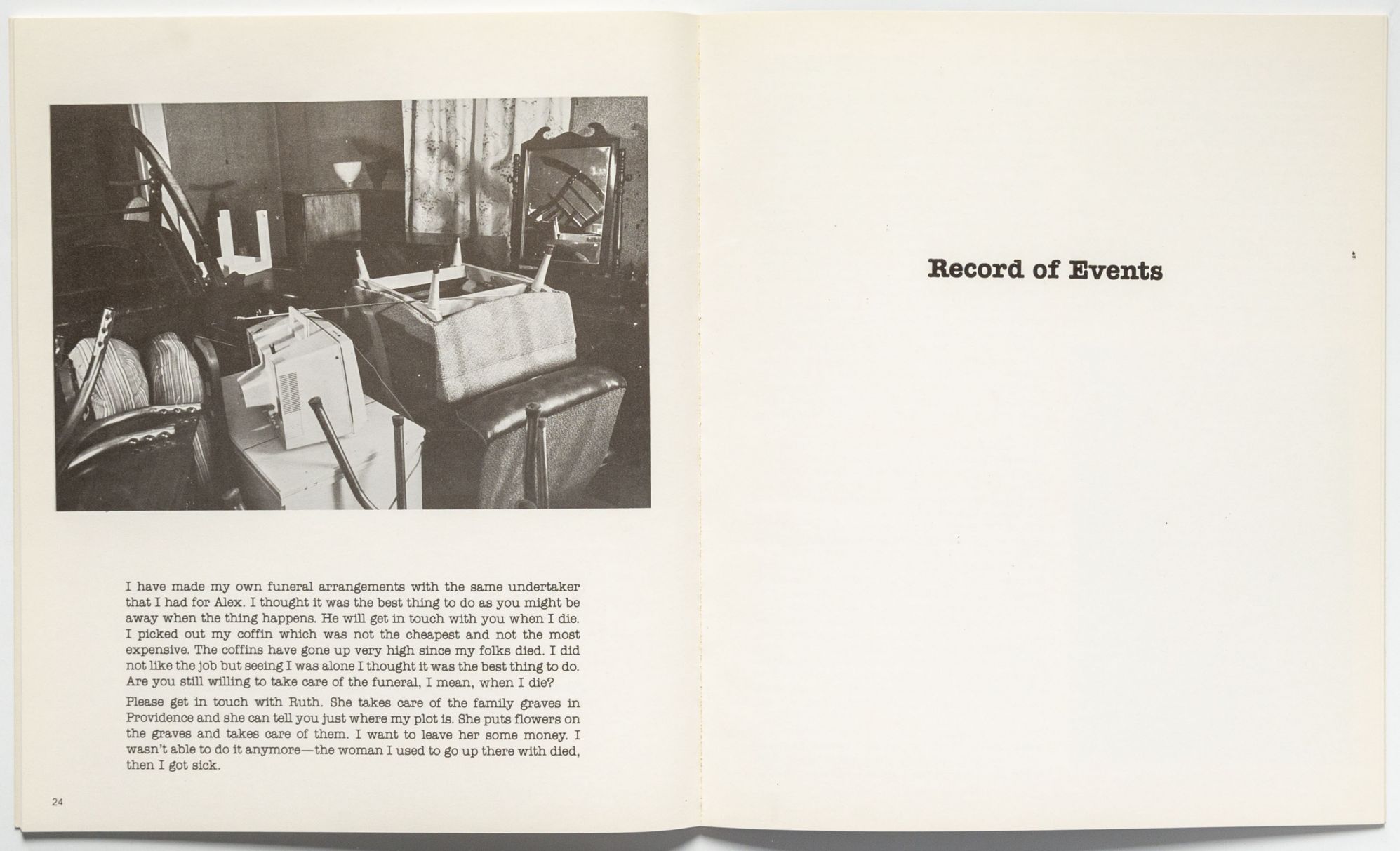

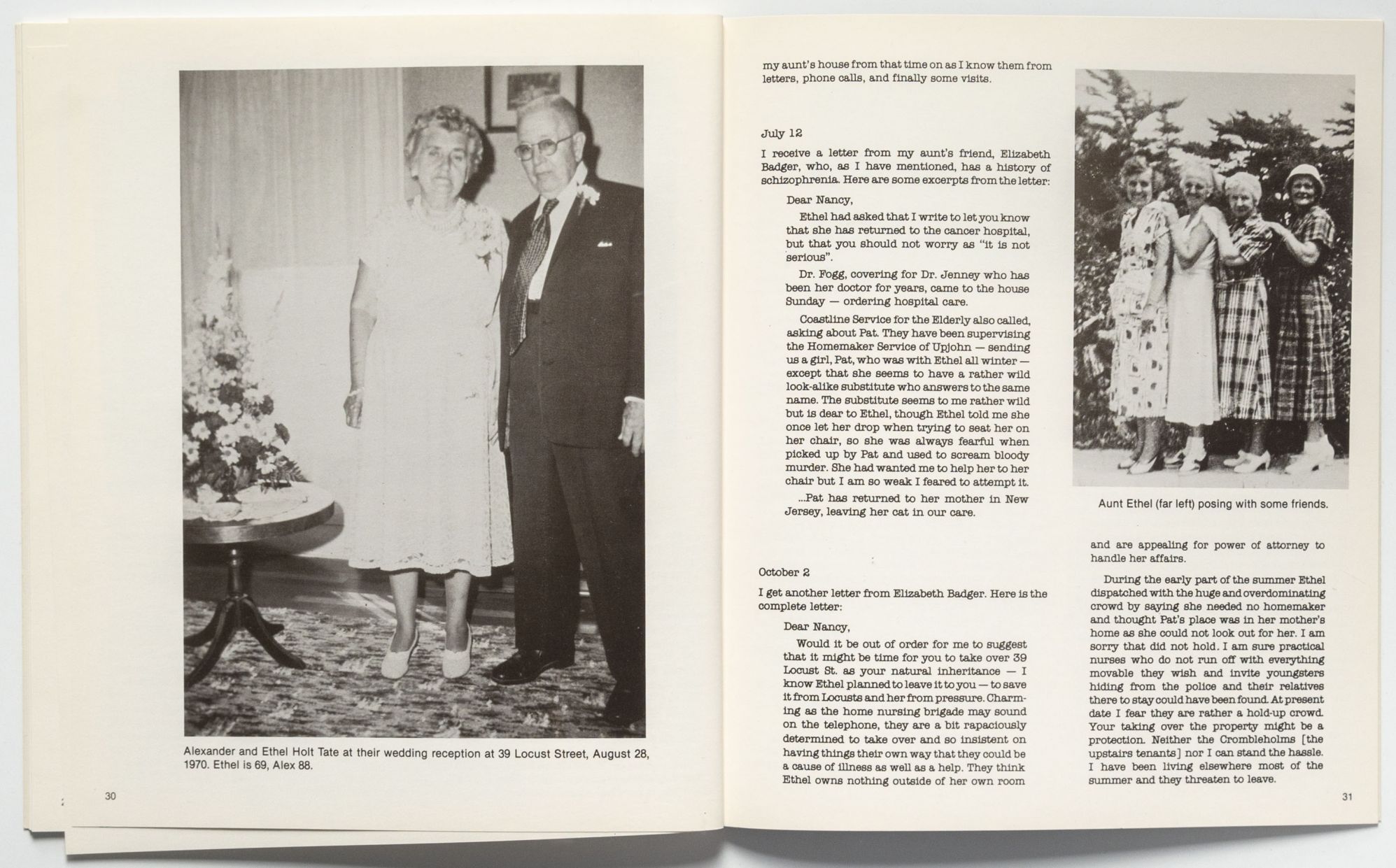

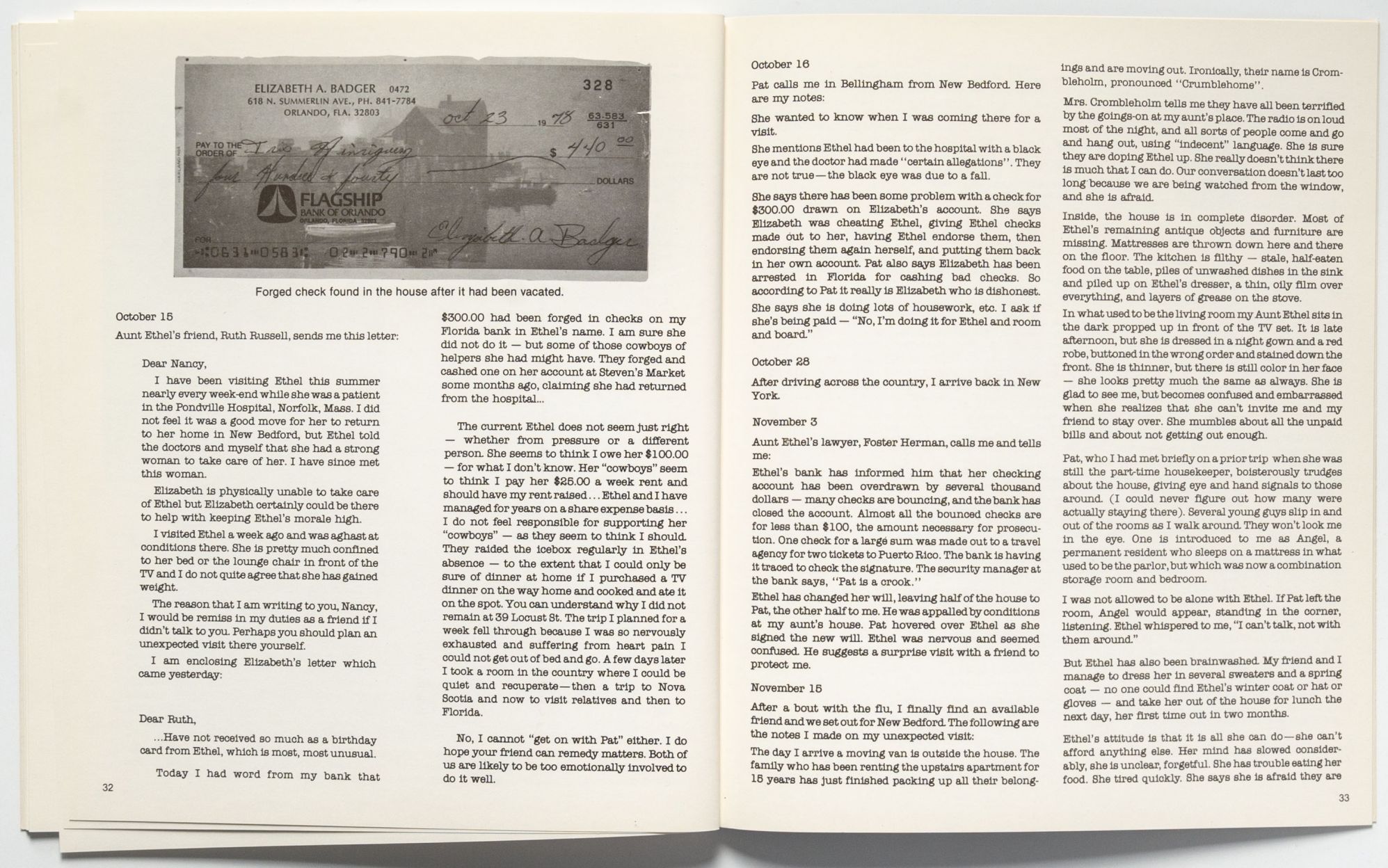

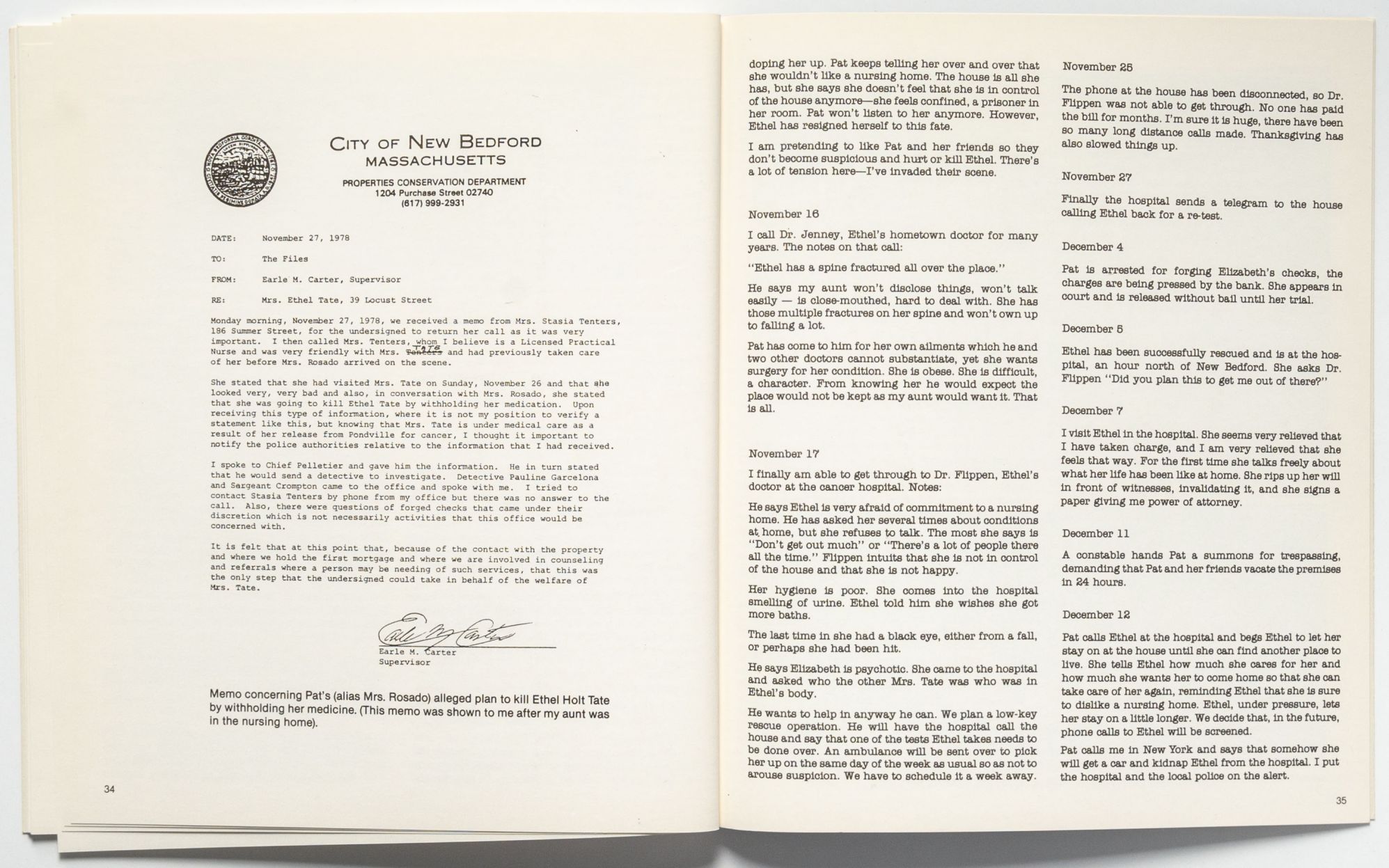

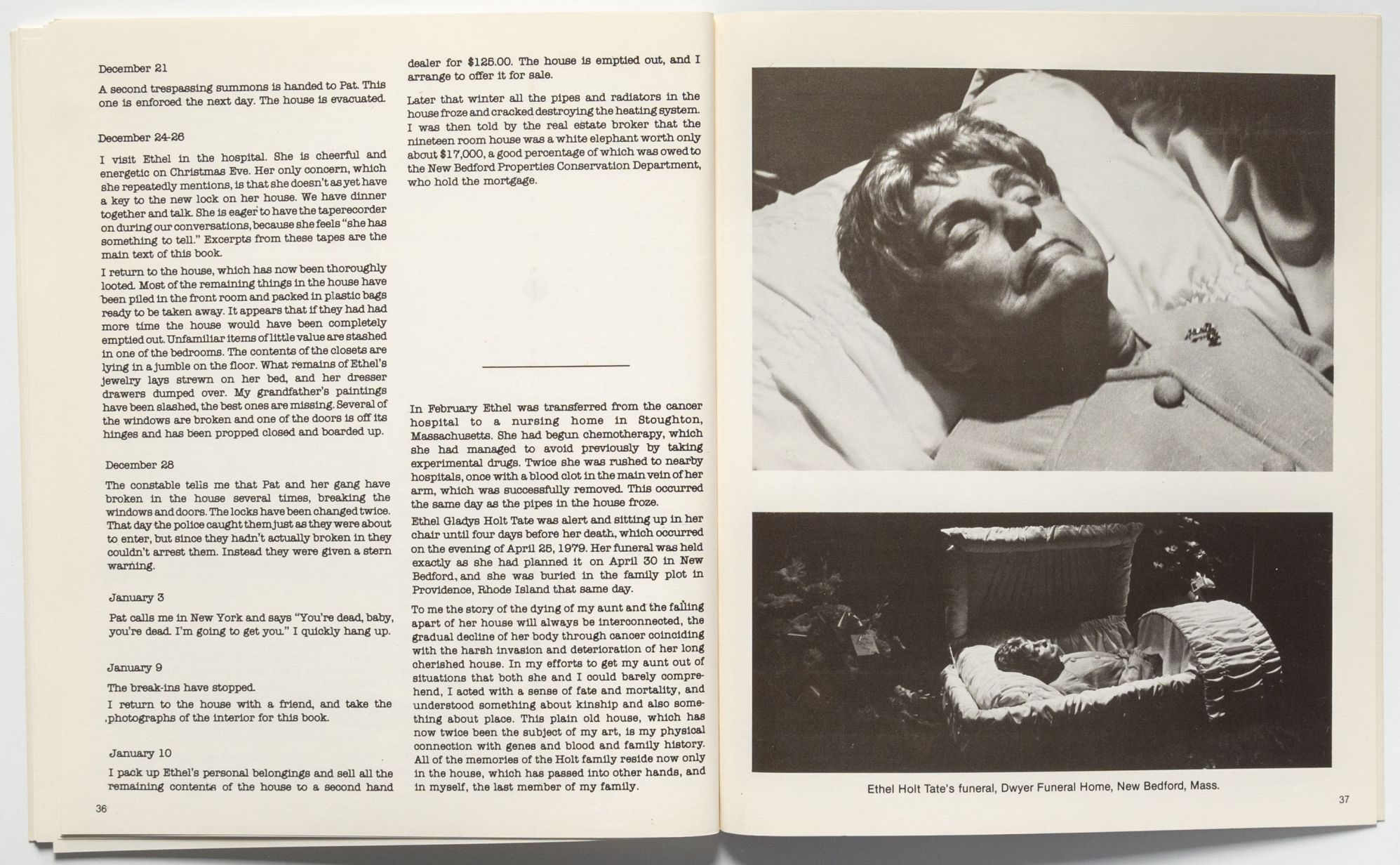

I’m also fascinated by the book’s two distinct approaches of combining photographs with text. The first half brings together Nancy Holt’s forensic-like photographs with brief and brutal quotes by her Aunt Ethel. In the second half we read Holt’s lengthy record of events alongside family photographs and other documents from Ethel’s life. Taken together, this slender paperback is a devastating record of a life broken and otherwise forgotten.

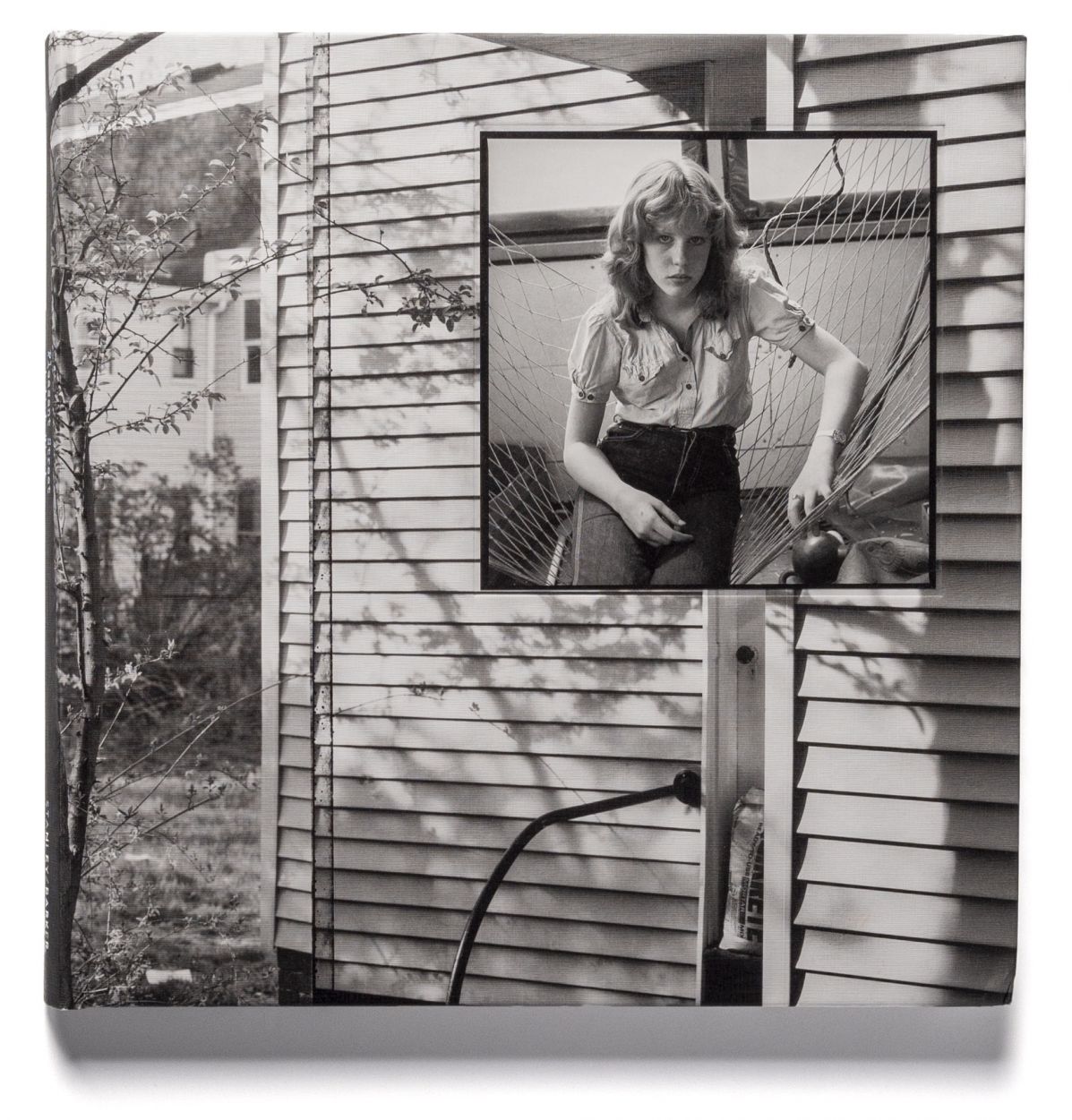

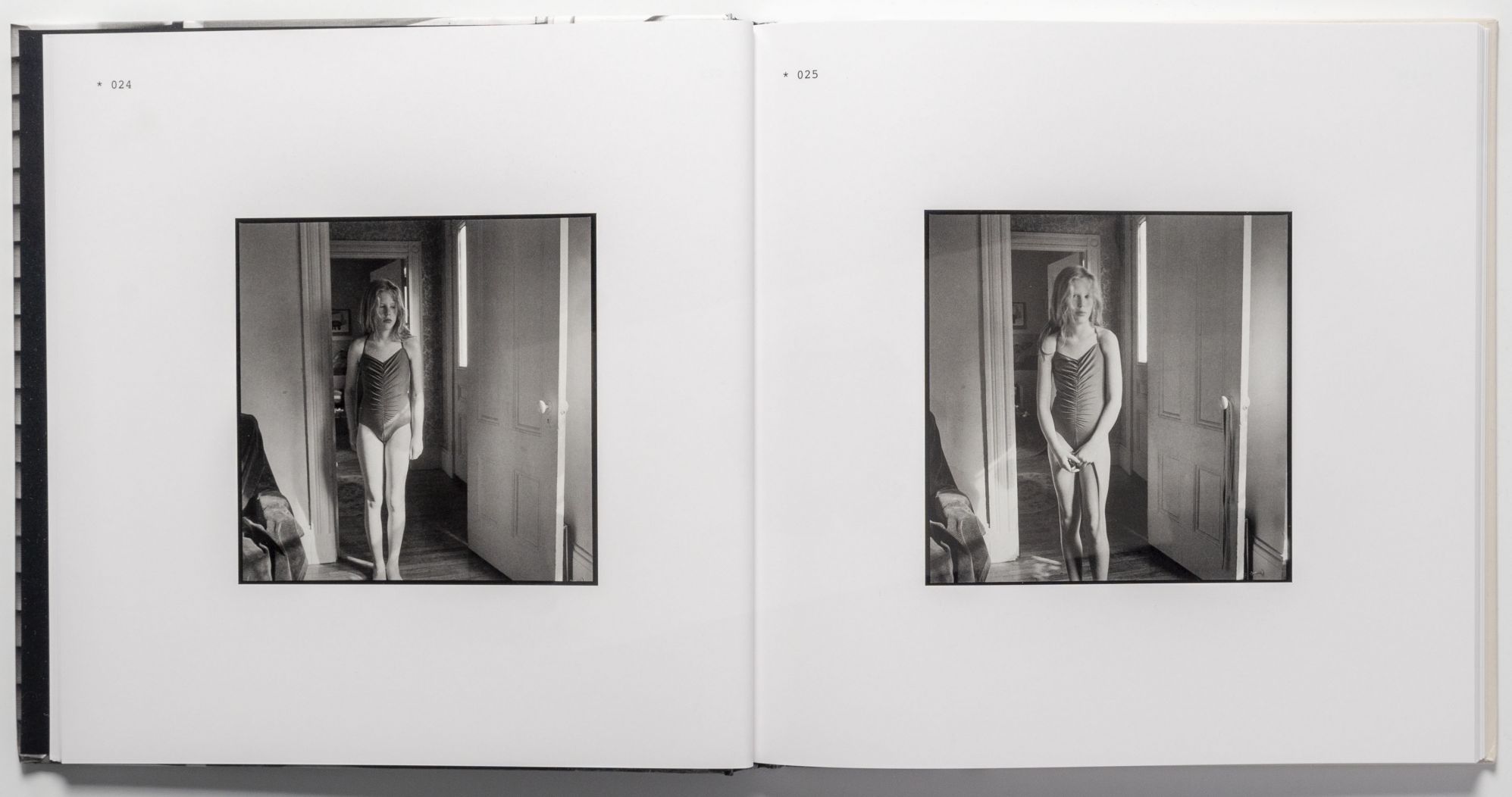

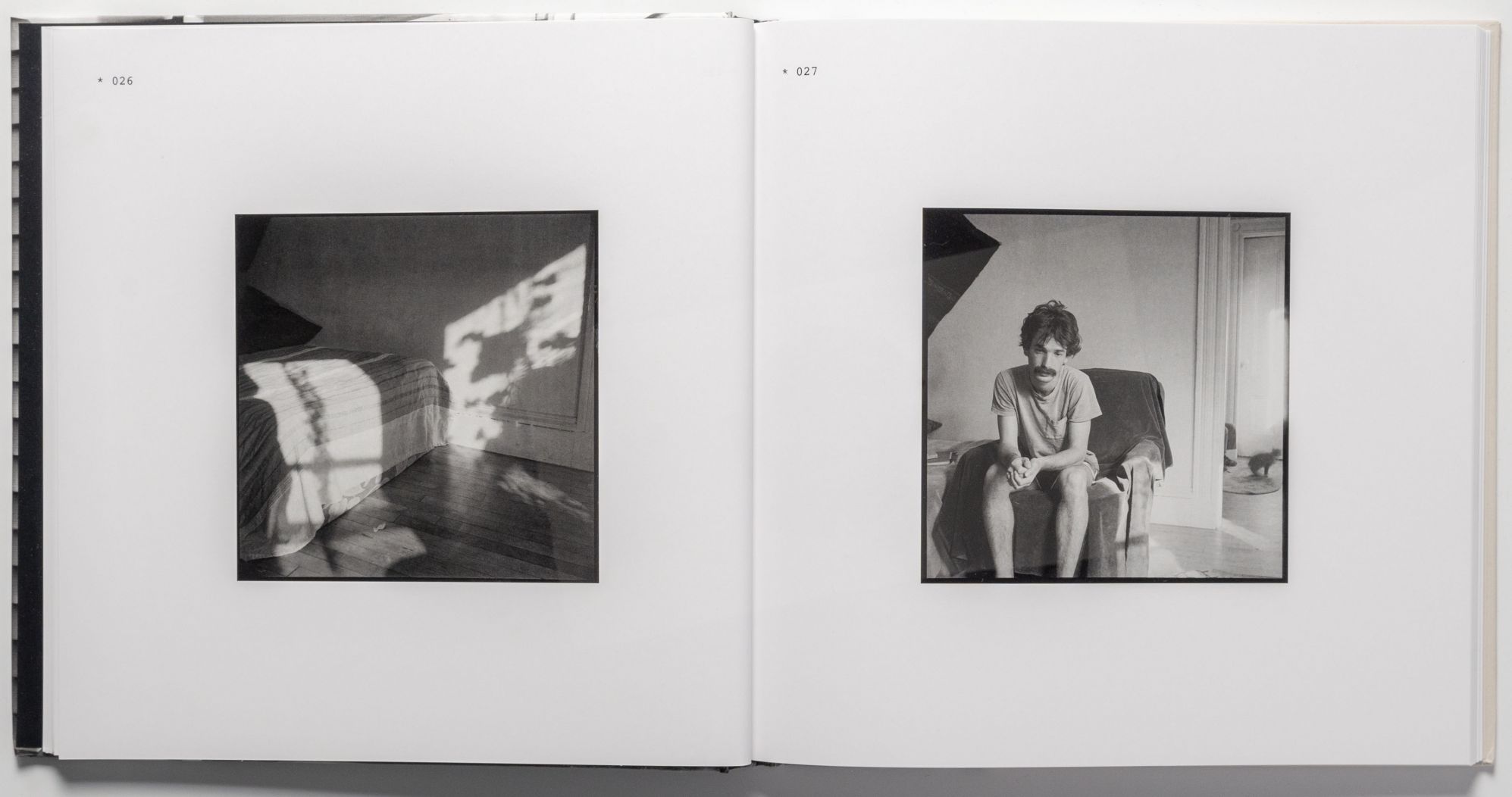

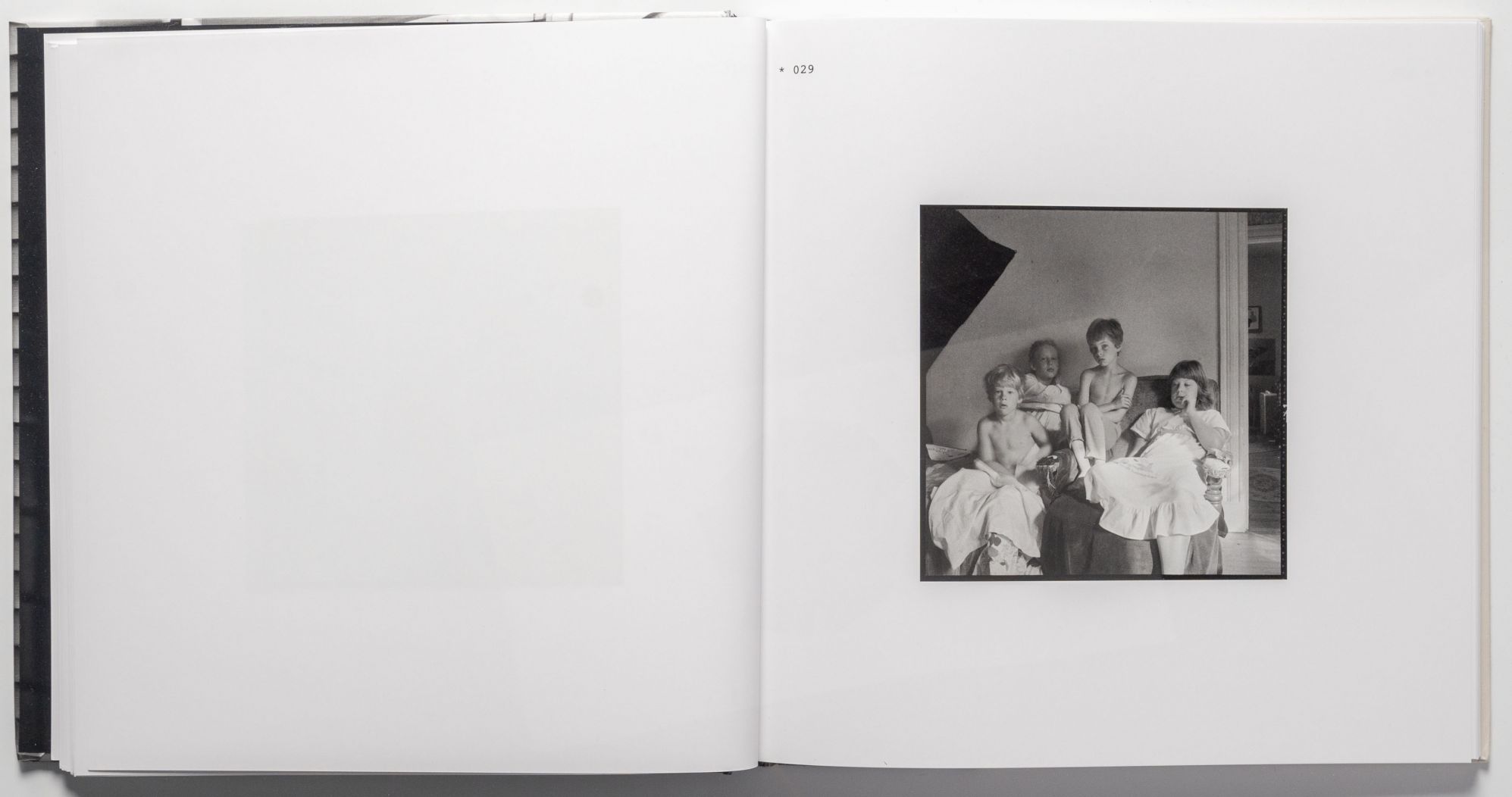

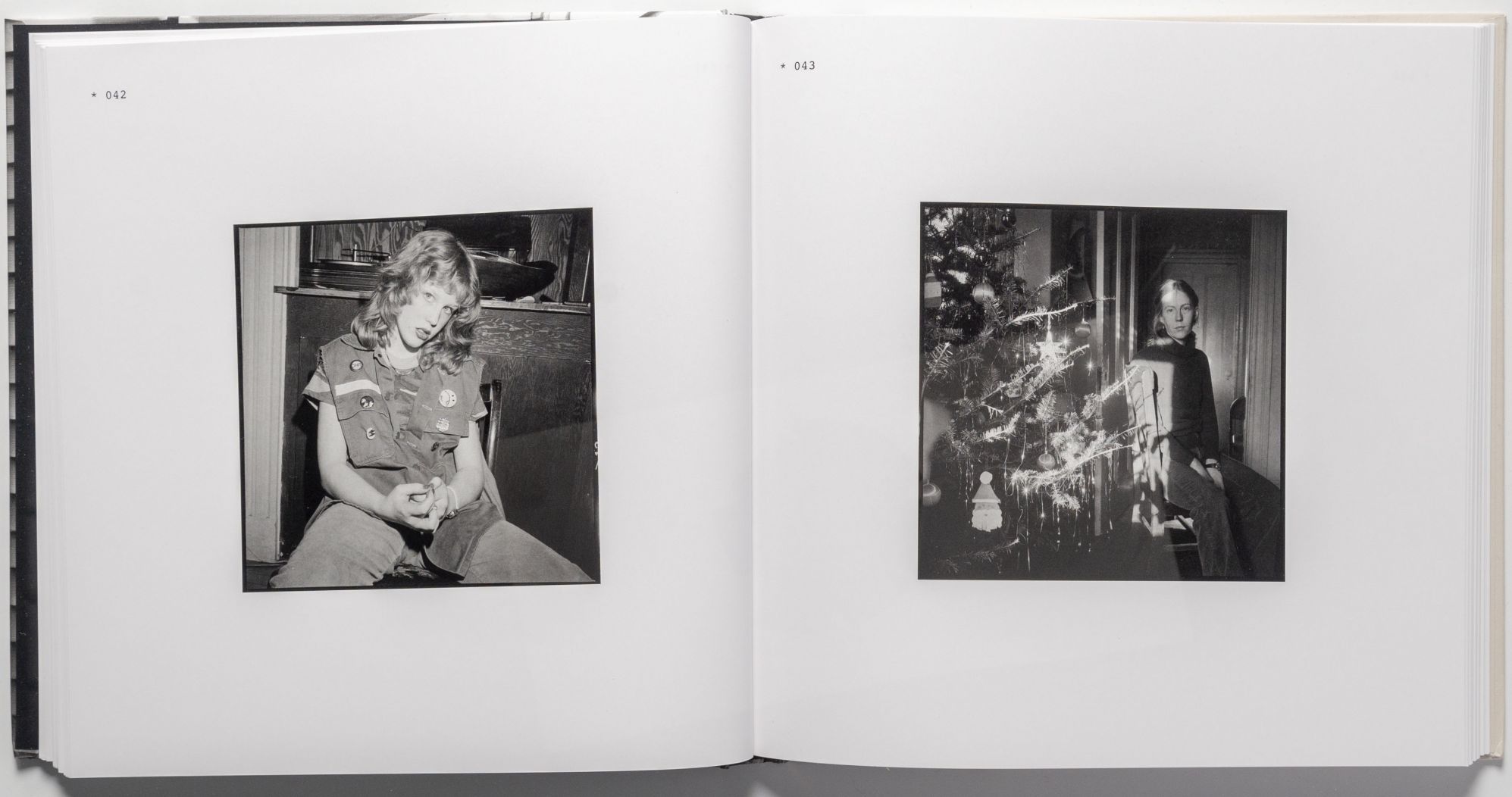

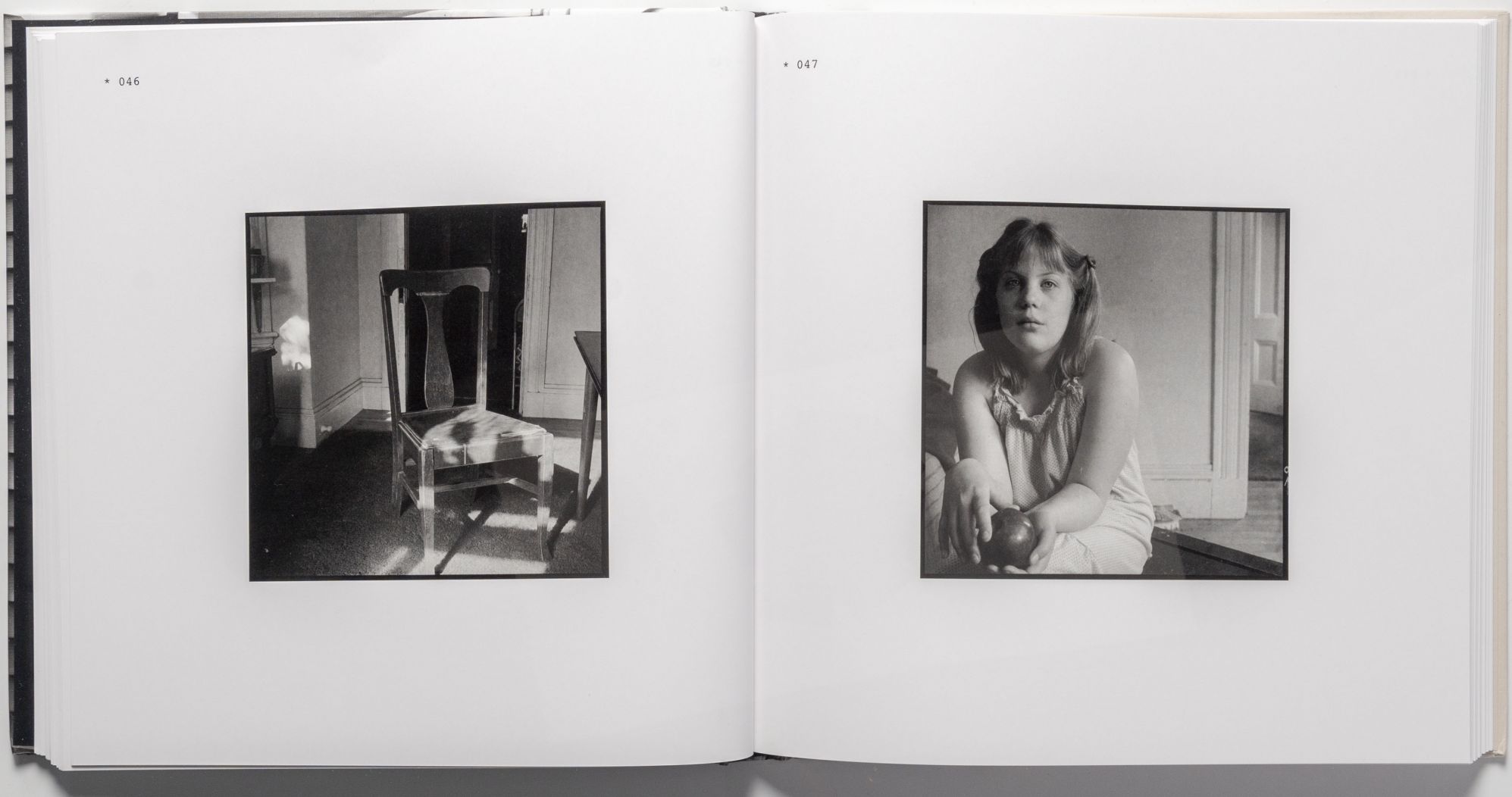

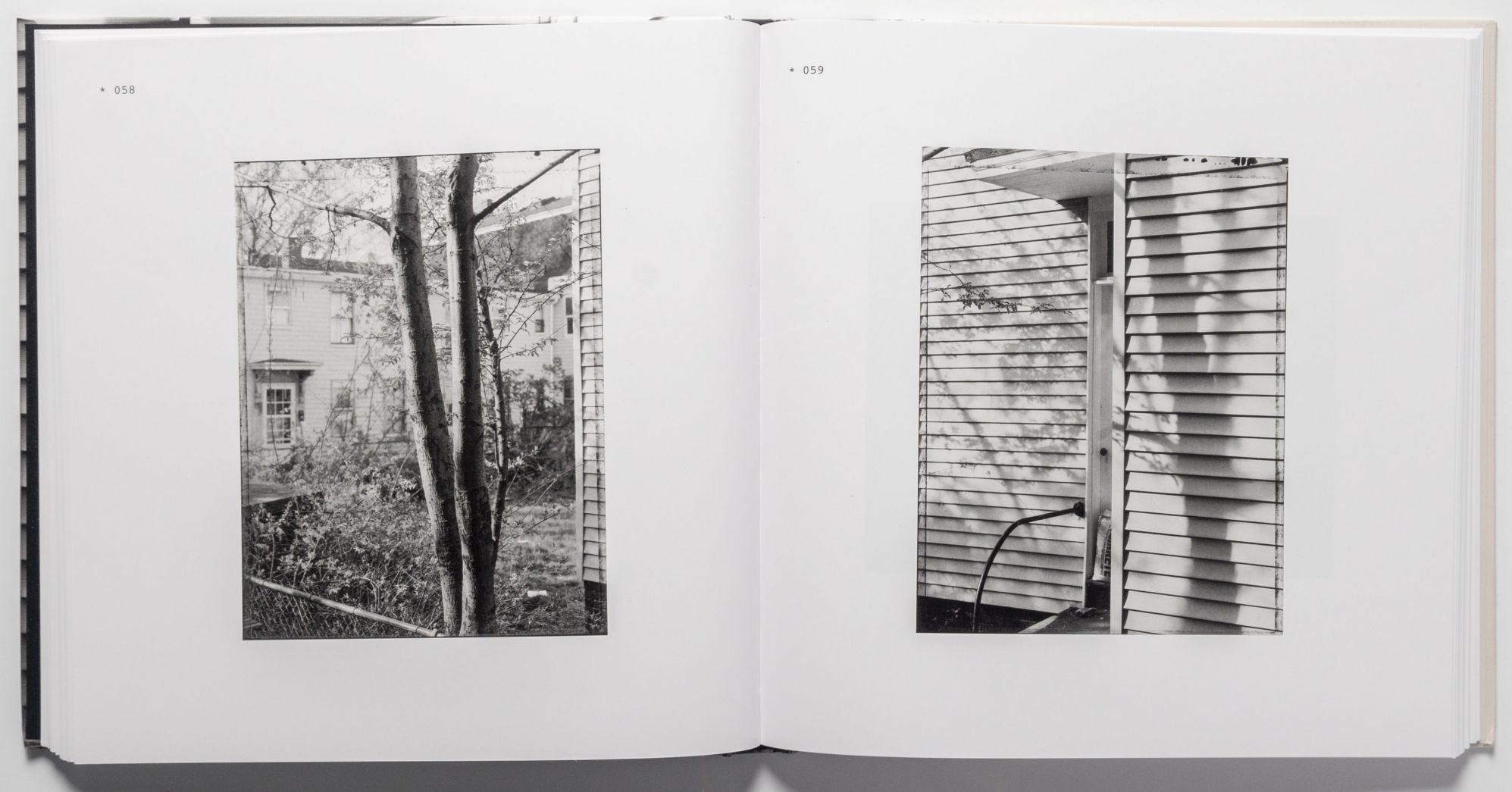

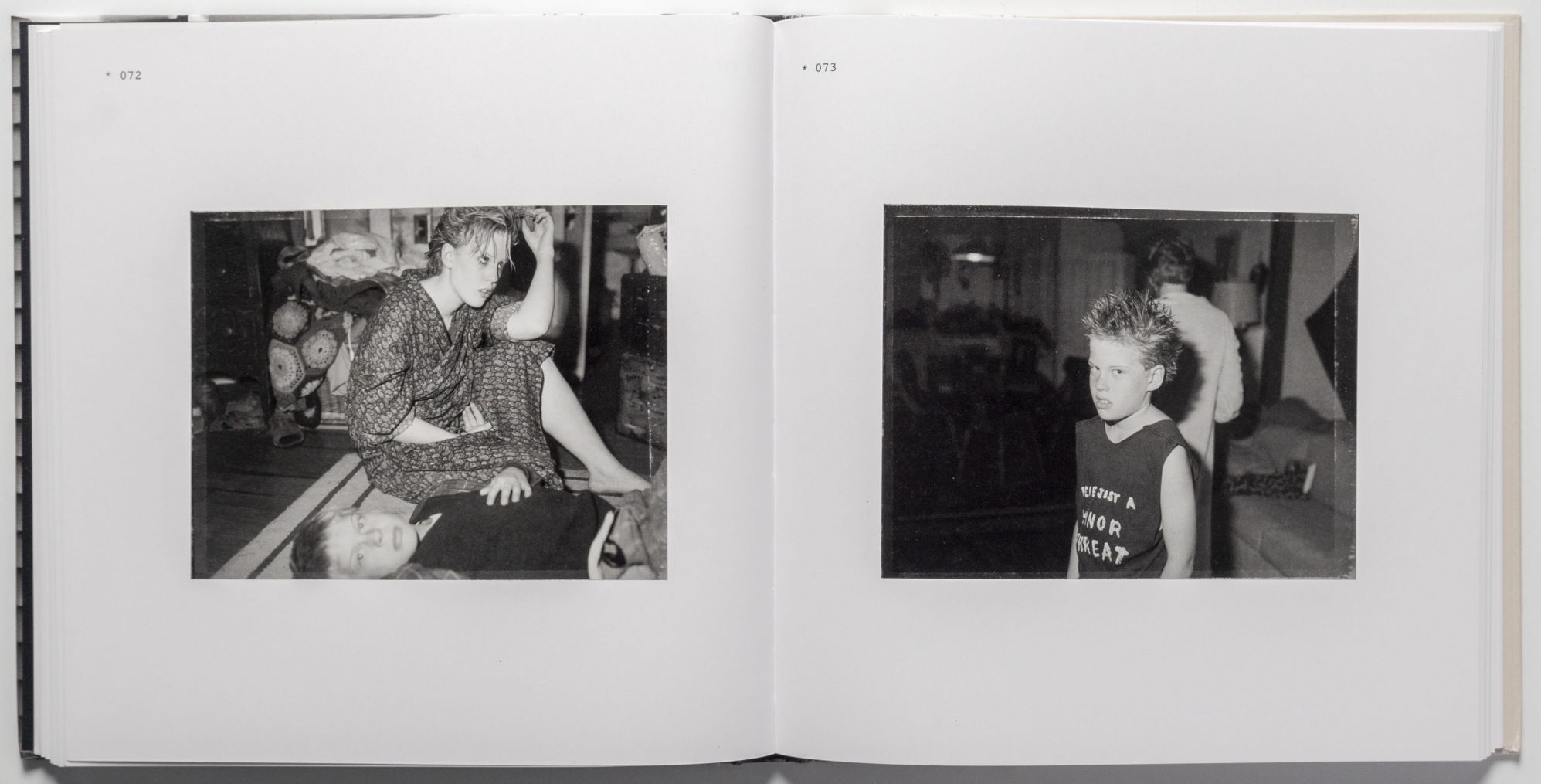

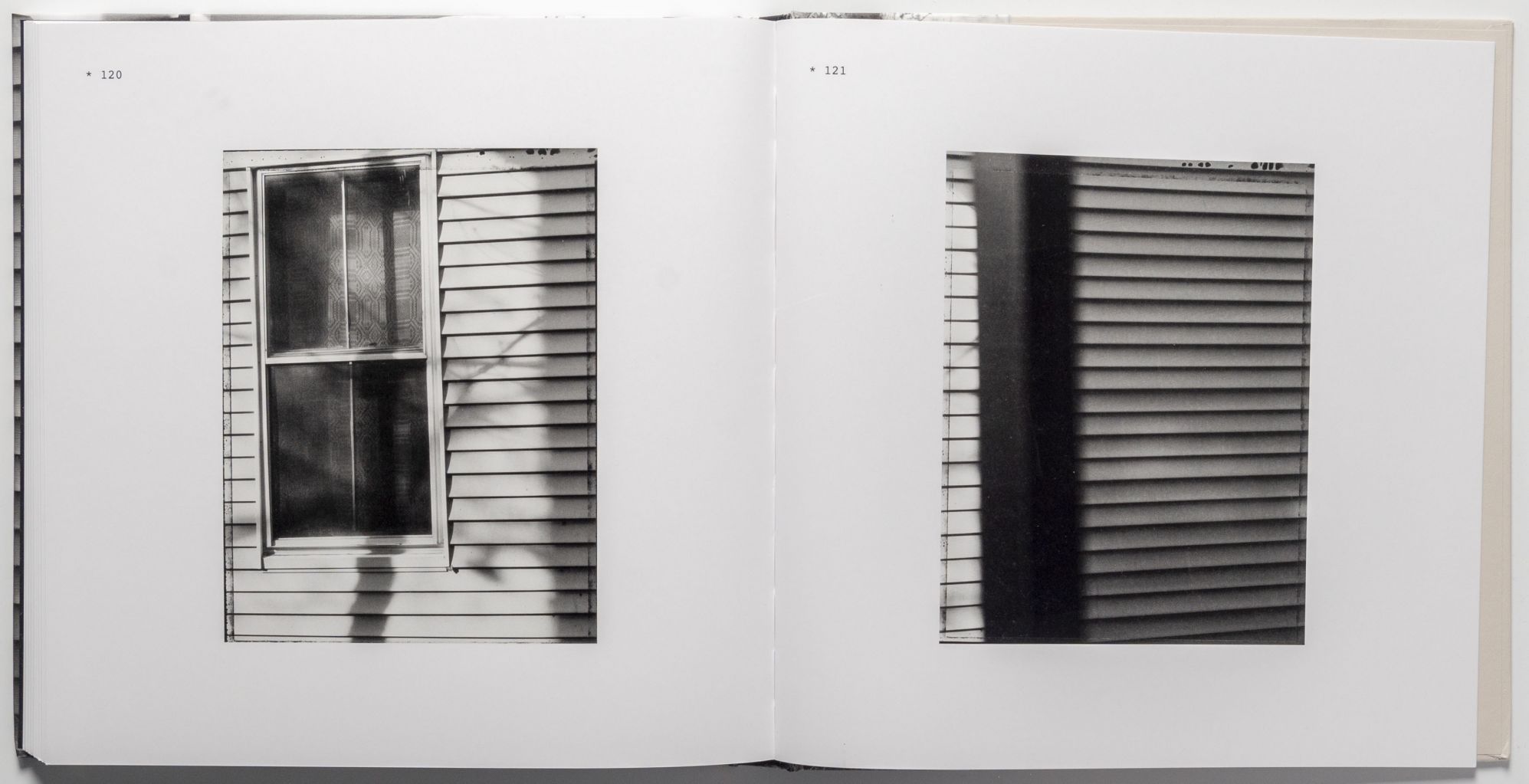

Recently Received: Pleasant Street by Judith Black

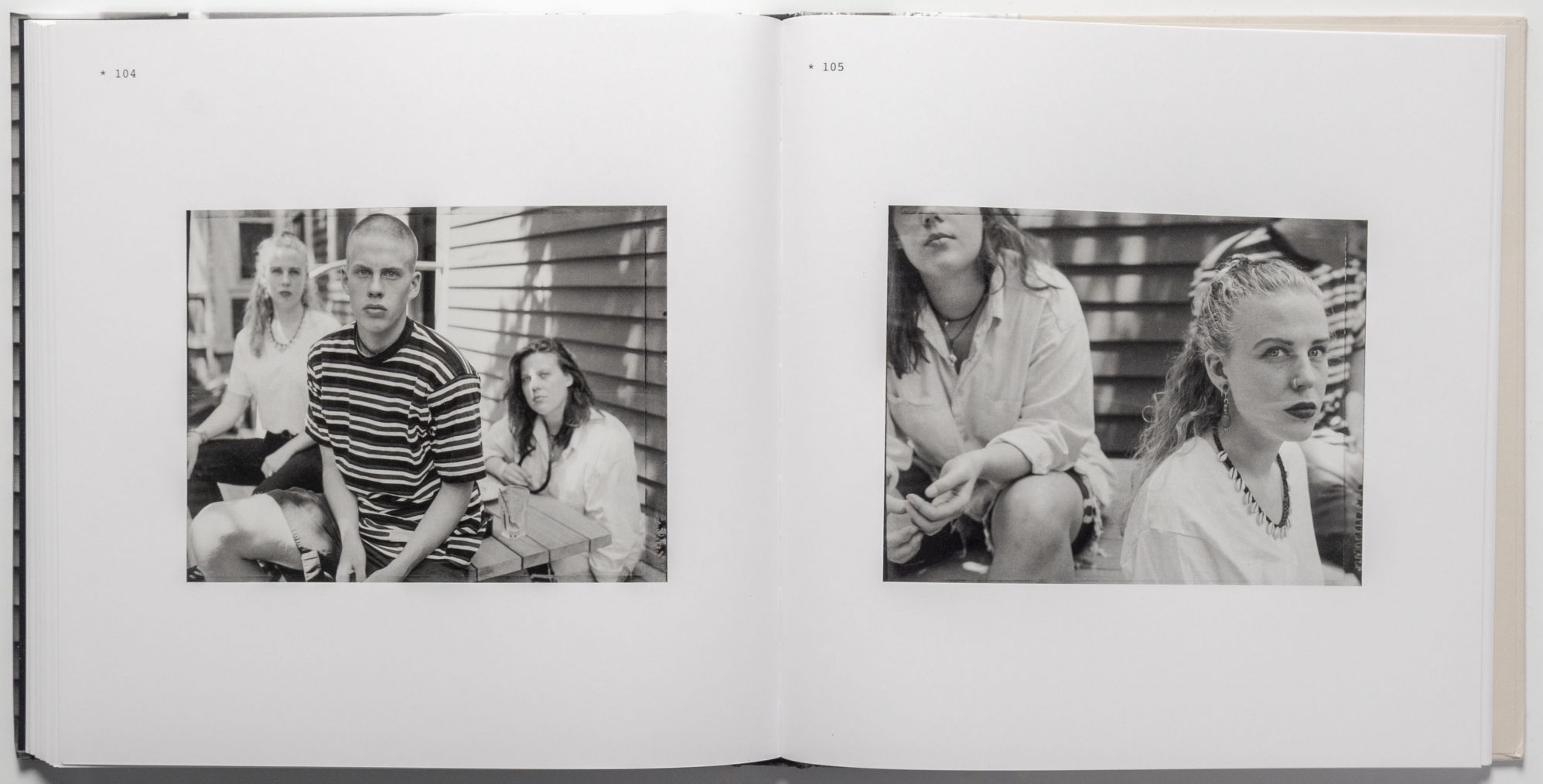

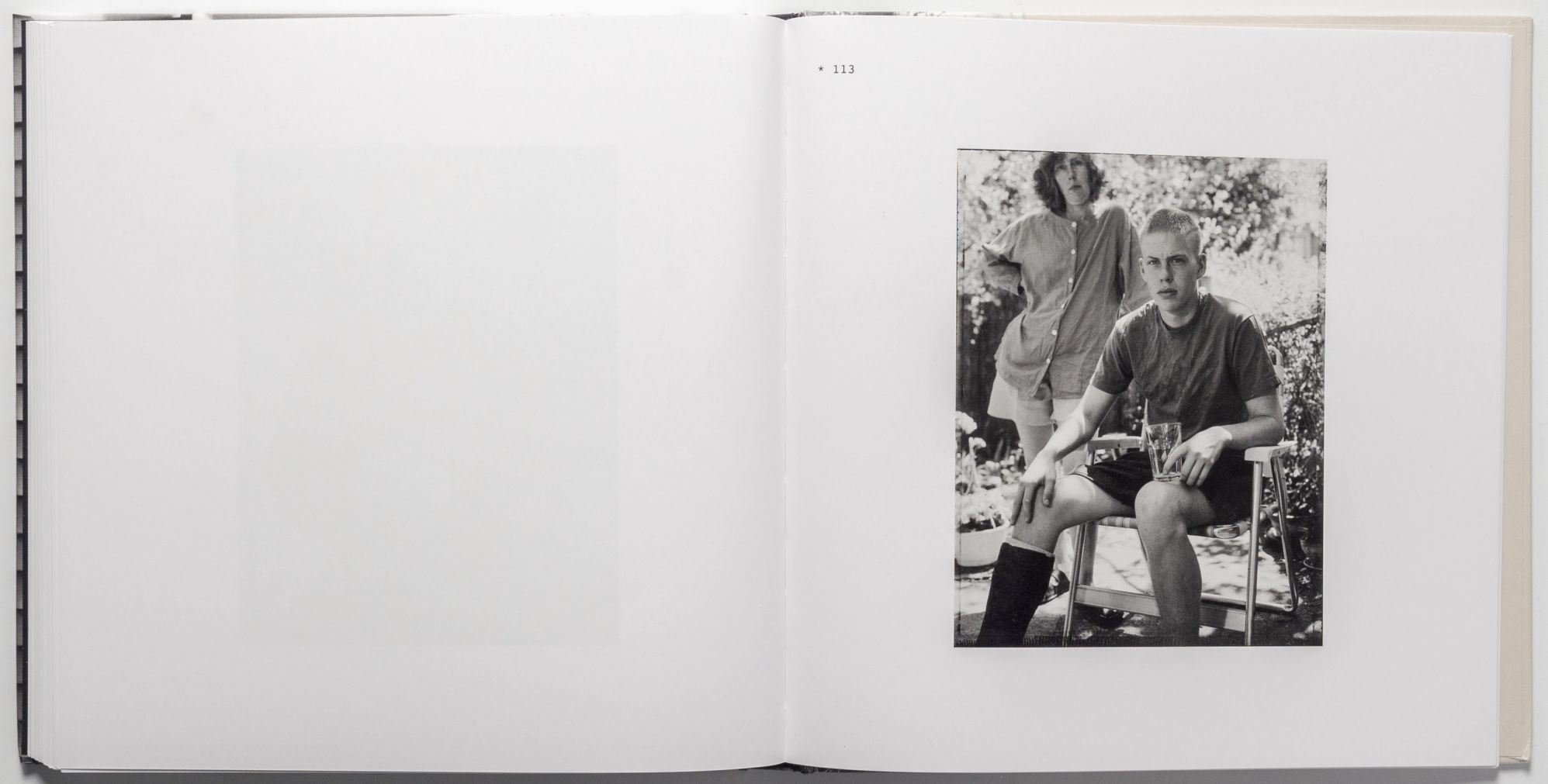

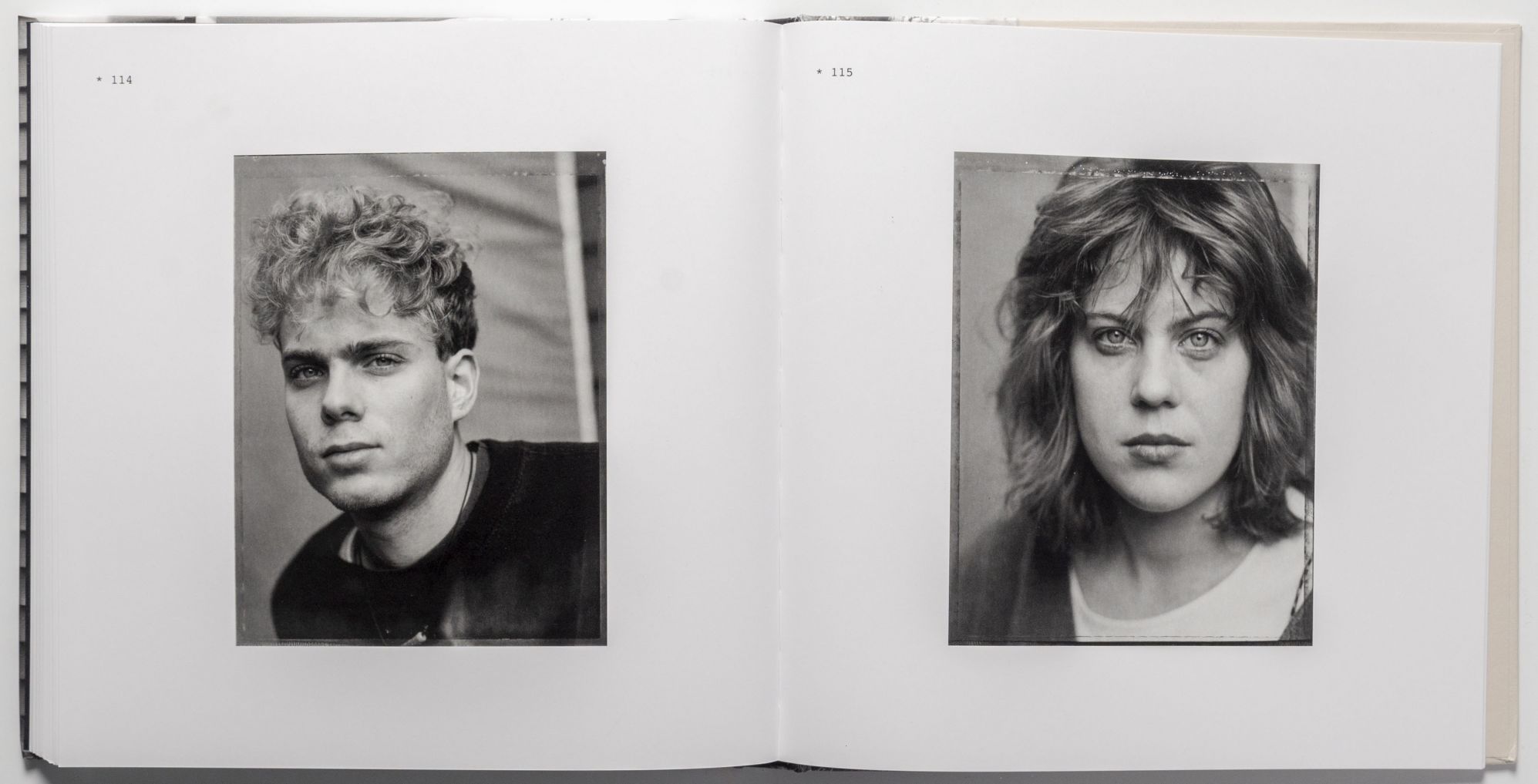

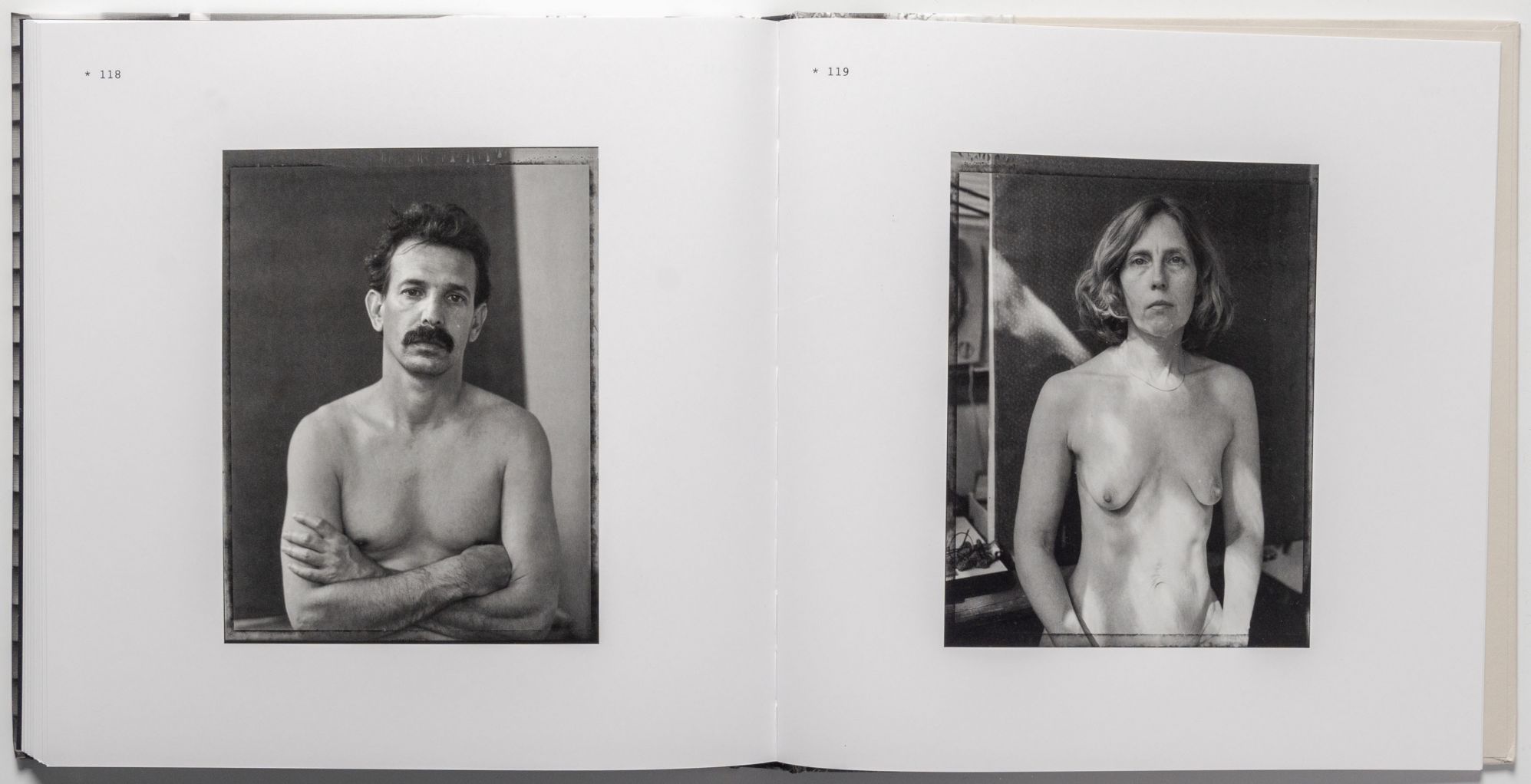

The most personally meaningful group photography exhibition I ever attended was “Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort” at MoMA. Part of this was timing – I was just beginning to discover photography when the show opened in 1991. But just as important was the subject. As a Midwesterner who felt not at all home in midtown Manhattan, it was comforting to see depictions of domestic life from across America.

“Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort” was Peter Galassi’s first curatorial outing after taking over the reigns of MoMA’s photography department from John Szarkowski. I assumed he would also follow in his footsteps as kingmaker. There were some examples – Philip-Lorca diCorcia was on the catalog’s cover and went on to become a superstar. But many of the artists in the exhibition fell away from the spotlight. This was particularly true for many of the twenty-eight female artists in the show.

Nearly thirty years after this exhibition, a number of these women are finally getting the attention they deserve. Excellent monographs of older work have been recently published by Mary Frey, Sheron Rupp, Sage Sohier and Jo Ann Walters. 2020 adds Judith Black to this list of under-recognized artists.

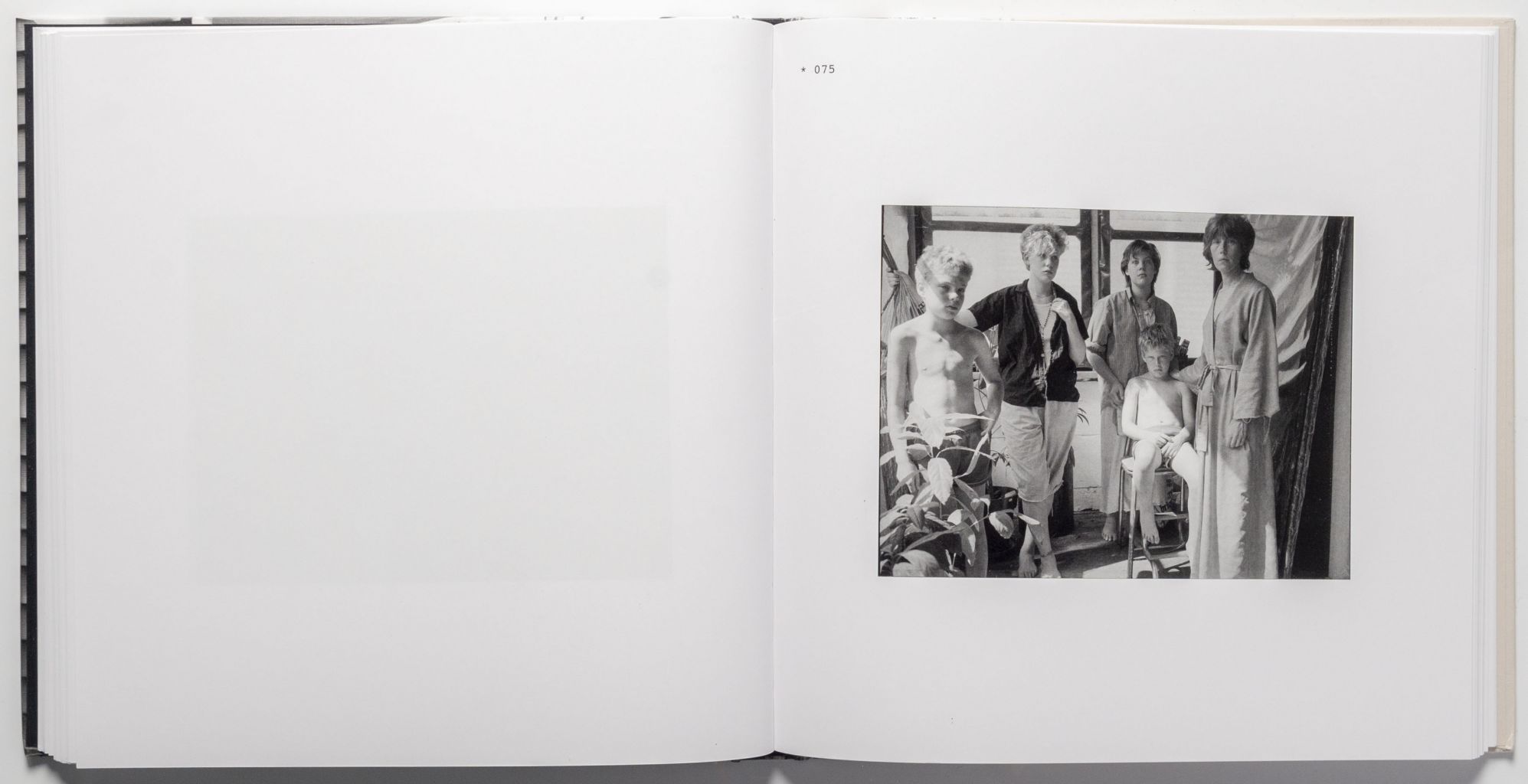

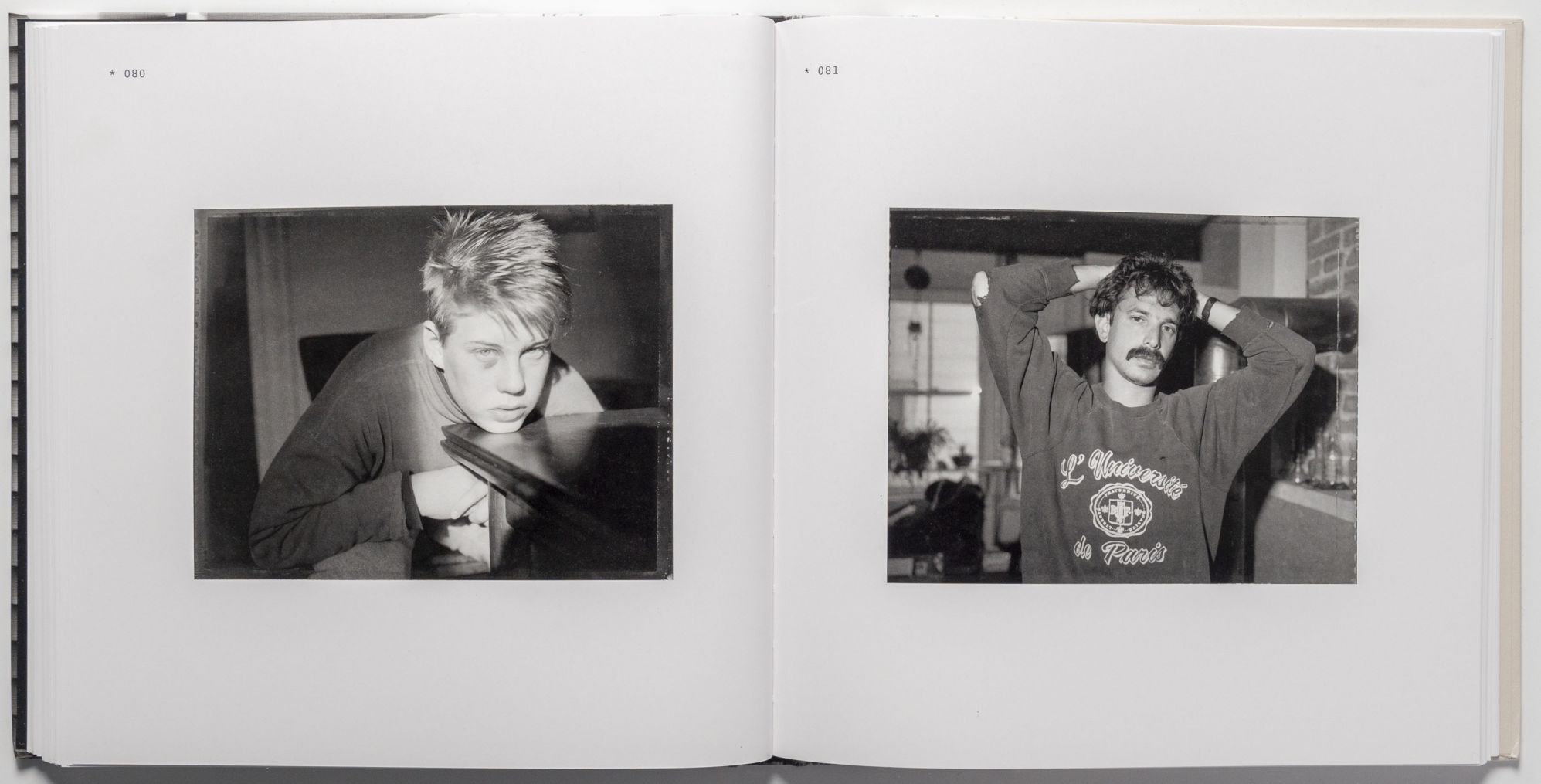

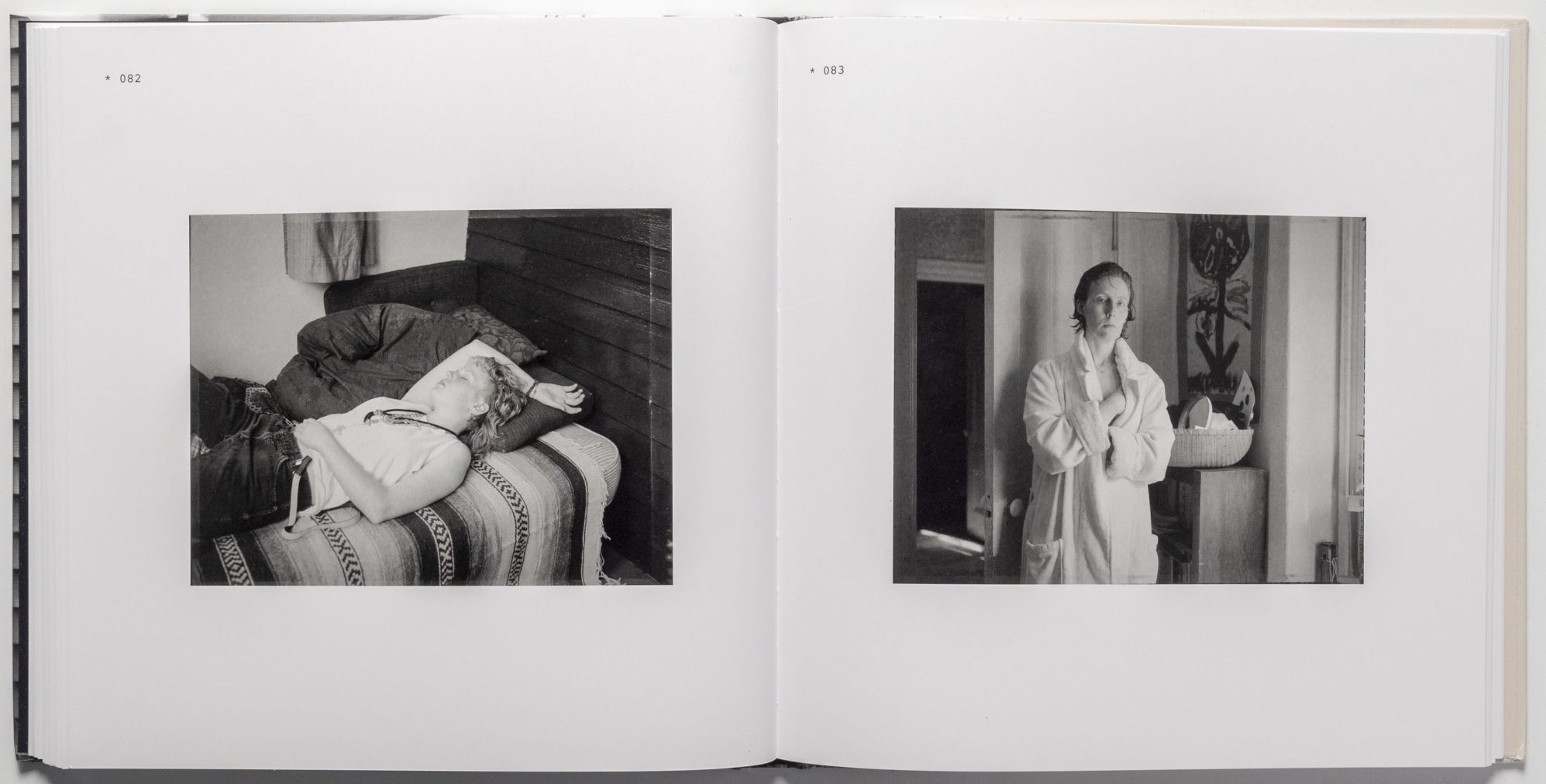

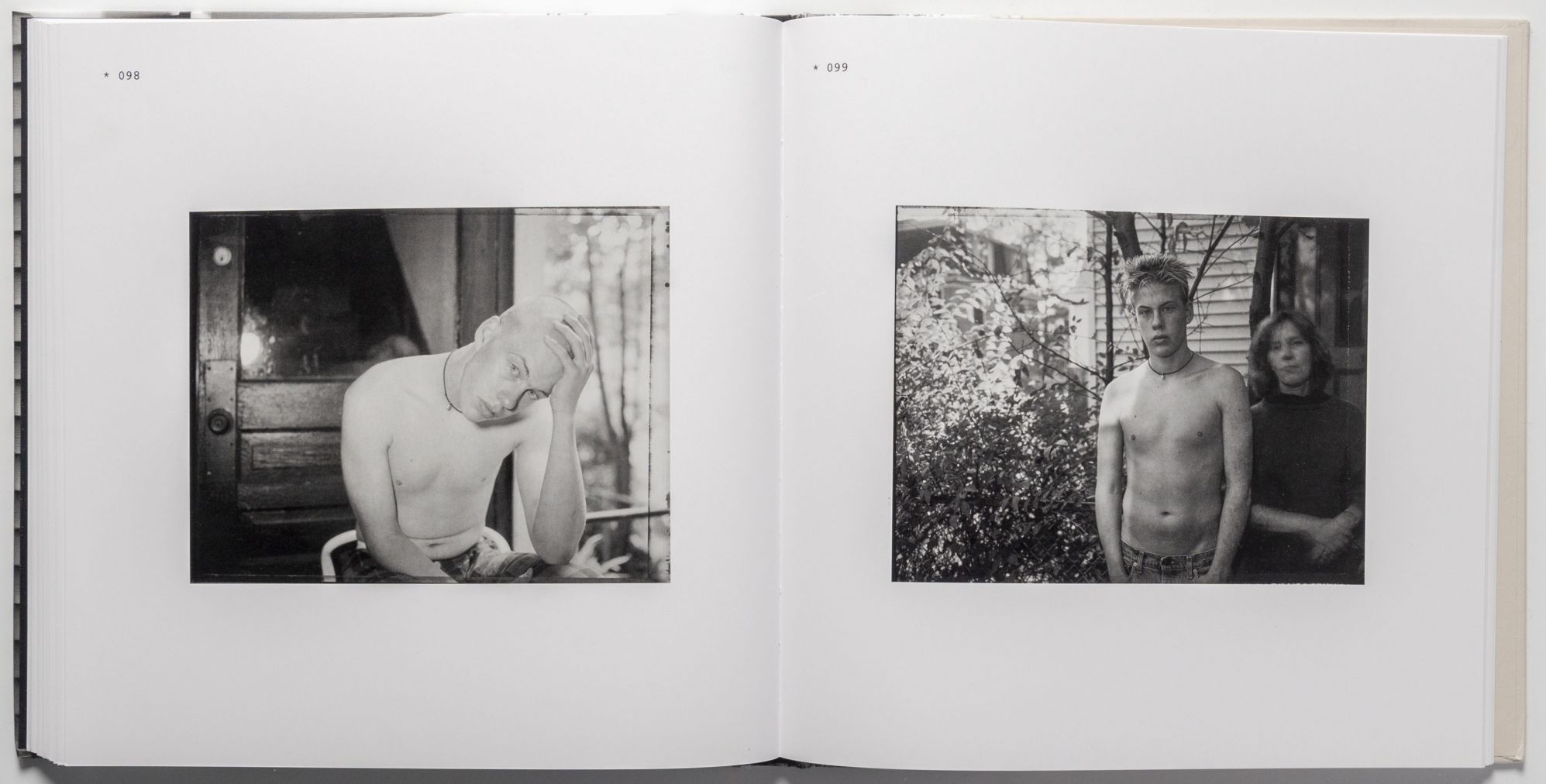

In the late 1970’s, Judith Black was a single mother of four children. In need of a way to earn a living, she moved to Cambridge to get an MFA in photography. “I quickly realized that I was not going to be able to roam the streets to make photographs,” she writes in the book’s introduction, “I had limited time between working at MIT as an assistant, attending classes, and being a mother. Our apartment was dark, but it became my studio.”

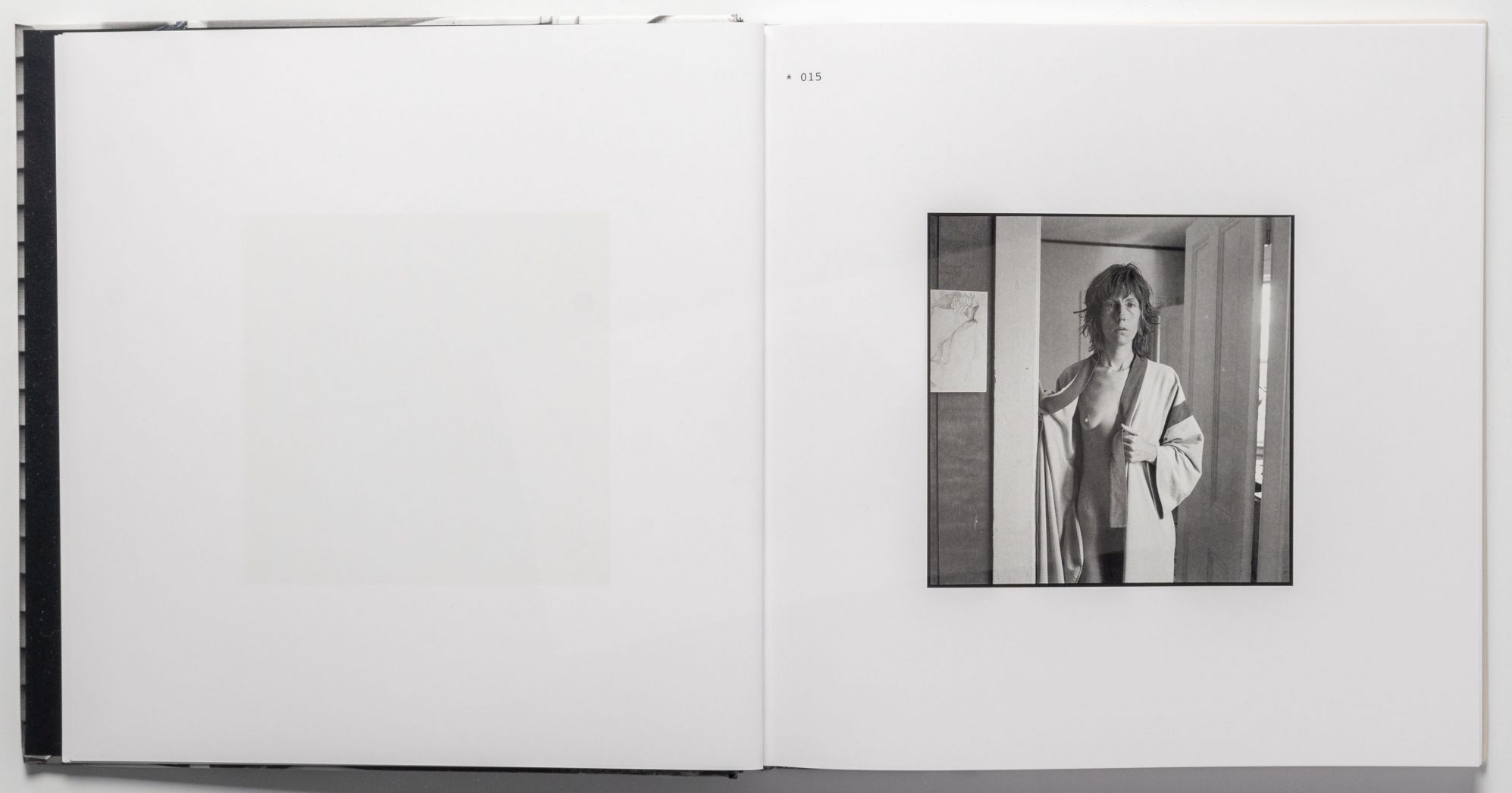

The photographs Black made in her home studio are understated and direct. We see four children, their step-father, a lived-in house and Judith Black herself. The power of the work comes from watching these elements slowly change over time. The first picture is of Black pregnant with her daughter Laura in 1968. The last image is of Laura pregnant in 2000.

While it shouldn’t have taken decades to see this work, it’s worth the wait. I feel the same rush of enthusiasm I felt when I first encountered Black’s work when I was twenty-one. Her photographs make the ordinary world around me feel more alive and worthy of attention.

The (virtual) Lunch Table

Ethan: The most intriguing thing I’ve watched lately is Portrait of a Lady on Fire. 8/10

Peter: I recently watched the 7-part documentary, Tiger King. I cannot recall a time when I felt more captivated and ashamed all at once. 9.5/10

Molly: These days as I continue to return to Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1986), I am reminded each time that life is different, then, now, and forever. I think it always is, but now it feels more tangible. 10/10

Ky: This week I hopped on the bandwagon and watched the entirety of Tiger King on Netflix, and wow, not what I was expecting! It definitely made me forget about our current situation for a bit. I think the best word to sum it up is bizarre, but totally worth the watch in my opinion. 8/10

Alec: The new Waxahatchee album, Saint Cloud, has been my Americana comfort food. 8/10