“Is not impermanence the very fragrance of our days?” -Rainer Maria Rilke

“Is not impermanence the very fragrance of our days?” -Rainer Maria Rilke

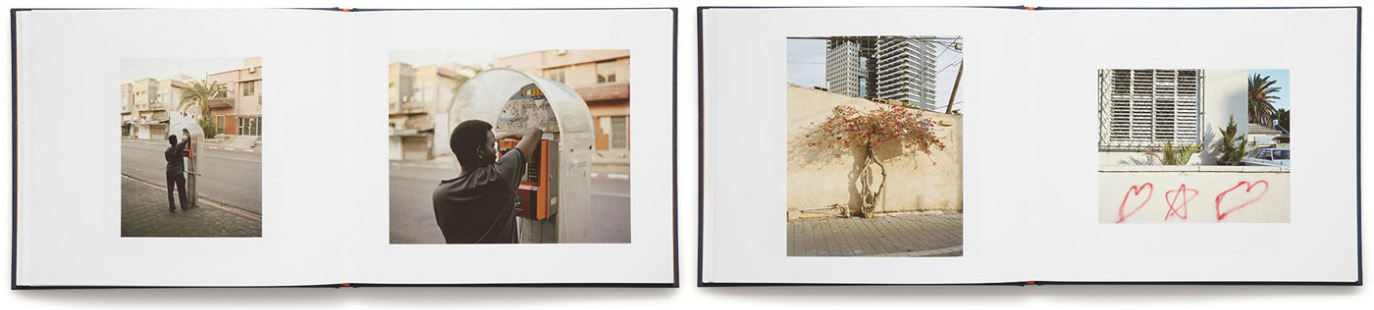

There are two stories in J. Carrier’s Elementary Calculus (MACK), actually a story within a story. Commencing after the title page, the first story begins with a photograph of an ancient stone wall on which a pigeon is perched, and ends with the last photograph of what seems to be that same pigeon in that same wall a few seconds later. Evoking all the associations of massive stone barriers, the story of the walls opens onto the historical: its inescapable presence, brute force, implacable logic, and incontrovertible permanence. Comprising the remainder of the book, the second story begins with the second photograph—an empty phone booth—and continues to the second-to-the-last photograph of another empty phone booth with the handset upside down. In comparison to the larger historical bracket, the second story is about a humble human activity, a simple phone call that almost inexplicably expands into a visual stream-of-consciousness, a day in the life as lived between walls.

The setting of both stories is the intractable historical terrain of Tel Aviv and East/West Jerusalem, a complex and disputed landscape defined on a daily basis by the visual conventions of mass media. But forget the Kalishnikovs and demonstrations; J. Carrier is after something else entirely. Using his own experiences as a migrant to guide his perceptions, Carrier maps the notion of migrancy across streets and alongside sunsets and especially in the public/private implosion of the Africans, Asians, and Palestinians he photographs at phone booths. It’s a revelation, a place in which the intransigent narrative of opposing sides has given way to the subterranean currents of global labor and its stateless wanderers. That said, Elementary Calculus isn’t a social documentary in the strictest sense: Carrier doesn’t depict the living conditions of migrant workers in graphic detail. Instead, he asks his viewers to do something more subtle and risky: to walk a mile in his migrant shoes, to see the world as a migrant sees it, to understand the world as migrants understand it.

In Carrier’s rendering, it’s a world that moves between beauty and anxiety, between bushes exploding into bloom and cats warily looking for shelter. It’s also a world in which migrants know other migrants, notice what other migrants notice, walk the same streets, use the same phones. The sequences pile up through recurring visual cues: African with shadow on sidewalk becomes cart with shadow on sidewalk containing fruit which become the markings in a graffiti die which become the popping buds on a tree branch which become the pock marks of an African’s face which become the roses in bloom on a bush. The historical appears as a checkpoint or a gate with a star of David motif, but it feels subsumed by the ongoing rush of visual associations. More than a simple formal arrangement, the sequential structure of Carrier’s story-within-the-story frustrates the explanations of historical knowledge in favor of the unexpected connections provided by the visual and experiential.

Using this open-ended process of association, Carrier constructs a bittersweet meditation on the nature of the transitory: from birds to fruit to the ever-present phone-callers. What is common to these images is exactly what is elemental to calculus: change, constant yet variable, is the underlying order of all experience. There are undeniable visual pleasures in this view of the world. But even the startling beauty of a lemon tree is tempered by the tragic realization that every moment is fleeting, every social space unstable, every phone call home a phone call about to end. If we believe Carrier, migrancy is nothing less than the inescapable and continuous experience of impermanence.

By nestling his experience of migrancy within the walls of the historical, Carrier has created a complex space of being in which the systematic knowledge of history and the associative empathy of everyday experience become a single visual field. Within this field, Elementary Calculus transforms a rambling depiction of the “the fragrance of impermanence” into an elusive call to justice. It’s not a simple story and the end is nowhere in sight for those condemned to use public phones and who, unlike Carrier, can’t go home. But by pleading for what is crucial to the lives of individuals against what is expedient for the powers that be, J. Carrier has dared us to look beyond the seductions of borders, of history, of walls and to imagine what it might mean to pledge allegiance to each other.

– Vince Leo

Next week I’m headed to Paris Photo where I’ll attend the 2012 Photobook Awards. Not only do I think Elementary Calculus should be shortlisted for the First Photobook prize, I think it is worthy of being named one of the best of 2012. It will certainly make my top 10 list of the year.

Speaking of which, the season of lists is right around the corner. I like these lists because they give some sort of order to the overwhelming quantity of material being published these days. But I’m also hungry for more depth. This is the reason I’ve invited the fantastic writer and photographer Vince Leo to review books on the LBM blog. Many thanks to Vince for his 2nd eloquent review.

– Alec

Hi, a beautiful essay that makes me want to explore this work for sure. A beautiful quote from poet very dear to my heart, not only because we carry the same name. The spelling mistake happens to me all the time and I tend to accept it most of the times, but for Rilke it has to me corrected: Rainer. Thank you and much respect

Rainer Hosch