My go-to coping mechanism for anxiety & depression is sleep. I know, I know, I should go for a brisk walk, but at least I’m not shooting heroin, okay? Plus there’s a creative upside. Many of my best ideas occur to me during that liminal space between wakefulness and sleep. My first book Sleeping by the Mississippi is the result of a lot of hypnagogic brainstorming.

A couple of years ago I woke up in the middle of the night with the idea for a new LBM project. I wanted to create a podcast about creativity that was meant to be listened to while falling asleep. My idea was to record in complete darkness while having an ASMR-like whispered conversation with another artist. I finished a few of these episodes, but never released them. My favorite was the first episode with Matt Olson. If you are curious, I’m posting it for the first time: THE LITTLE BROWN MUSHROOM PODCAST.

In this newsletter:

- Picture & Poem: Setting the Table by Matthea Harvey

- Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: The Sleeping Prophet

- Dear Lester: Crushed Greystone? & An Assignment

- Ex-Libris: “The Sleepers” from True Stories by Sophie Calle

- Recently Received: EVOKATIV by Libuše Jarcovjáková

- The Lunch Table

Picture & Poem:

This newsletter originated from a lunch table conversation, not sleep, but with each issue I hope to make some dream-like connections. The best way for me to get this ball bouncing is by looking at my collection of anonymous photographs and reading poetry. I started by going back to one of my all-time favorite poems, The Sleepers, by Walt Whitman. This led me to Allen Ginsberg’s horny homage, “Love Poem on Theme by Whitman” and Robert Bly’s humanist take, “After Reading ‘The Sleepers.’” Perhaps I should take some comfort from these lines:

I go with my friend to the old country, we knock on the door of the house.

The old man comes to the door carrying a book of poems.

That night we sleep; we have so much forgiveness of all those who sleep:

The corporate criminal sleeps in his cell,

Our dim-witted president, out of touch with reality, sleeps,…

The defeated candidate sleeps, his wife is relieved.

Bly’s poem is clearly written by someone fully awake, perhaps while watching CNN before bed. It’s not the surreal medicine I need. After poking around I finally found a poem that walks the liminal fishing line where I find inspiration:

Setting the Table

by Matthea Harvey

To cut through night you’ll need your sharpest scissors. Cut around the birch, the bump of the bird nest on its lowest limb. Then with your nail scissors, trim around the baby beaks waiting for worms to fall from the sky. Snip around the lip of the mailbox and the pervert’s shoe peeking out from behind the Chevy. Before dawn, rip the silhouette from the sky and drag it inside. Frame the long black stripe and hang it in the dining room. Sleep. When you wake, redo the scene as day in doily. Now you have a lacy fence, a huge cherry blossom of a holly bush, a birch sugared with snow. Frame the white version and hang it opposite the black. Get your dinner and eat it between the two scenes. Your food will taste just right.

Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: The Sleeping Prophet

Over the course of his lifetime, from 1877 to 1945, Edgar Cayce aka the Sleeping Prophet, delivered more than 14,000 psychic readings in a self-induced trance. In the middle of the winter when I first showed up in Virginia Beach, stories of its famous former resident drifted two miles down the water to me—or perhaps I drifted north to them.

*

In Virginia Beach the waterside avenues are named for oceans and seas—Arctic, Baltic, Pacific, Mediterranean and on 67th Street, just off Atlantic, is a former hospital dating to the 1920s, green shingles and a wall of sunrise-reflecting windows—Magic Mountain by the ocean. A city bus stops outside the main visitors’ center, which looks very much of its own era, 1975. Both are collectively the headquarters and legacy of Edgar Cayce’s A.R.E. (Association for Research and Enlightenment) a few blocks from the ocean. The A.R.E. has been carrying on long after Cayce’s death in 1945; today it is a site of spa treatments and holistic seminars and trainings and study groups. Psychics give readings out of a little room attached to the bookstore, presumably all while awake. Upstairs, I’d heard, is Cayce’s original couch, ordered out of the 1909 Sears Roebuck catalog.

I have to admit, I was less interested in what Cayce said in his readings than I was in his process: psychic reading as creative output. Jealously, I wish it were possible to sleep-write, though I fool people on the regular. If I answer the phone when I’m working, nine times out of ten the caller will apologize, so sorry, did I wake you? It feels both embarrassing and pretentious to answer, honestly, no, I was just writing.

Every time I had passed by the A.R.E., it looked like things were really hopping. Lots of cars, people getting on and off the bus. After-hours skateboarders ollieing the stairs, women friends in matching outfits, boy-girl couples in matching black lipstick, lone dads, former Marines, retiree vacationers. I wondered which of Cayce’s big subjects—medicine, holistic healing, dreams, reincarnation, Egypt, Atlantis, and so on—drew them there. The Beat writers Neal and Carolyn Cassady were big Cayce people. When I was working on a story about the 1975 disappearance of the musician Jim Sullivan, also a reader of Cayce, Jim’s son told me that, years later, his mother had traveled from California to the A.R.E. for a reading; it helped her come to terms with the mystery of his vanishing. One day I noticed an eighteen-wheeler among the cars in the parking lot. Perhaps its driver was making an inquiry of their own.

Inside, I didn’t see any clairvoyant long-haulers or psychic-seeking truckers, but to my left was a painting of three white pyramids plunged on a bright green island (Atlantis?), and along a back wall, the details of Cayce’s early life unspooled on a timeline. A birthday the day before my own—Cayce was a Pisces, duh. Bookstore jobs. Predictions since childhood. Memorized whole books by sleeping on them. Was considered “strange.” Became…a photographer.

At the front desk a volunteer starting her shift swapped out the nameplate of the previous greeter, replaced it with one that read Cat Lady, and directed me upstairs, to the library.

*

Most of the accounts of Cayce’s life are related through dictated memoirs by his friends, and a biography written in the close-third person, which freely wanders in and outside of the sleeping prophet’s mind. Wesley H. Ketchum, who would enlist Cayce to help cure his patients through the more than 14,000 readings he gave while sleeping, dates their first encounters in that town to around 1907 or 1908: “He was there when Halley’s Comet was over, and that was 1910,” Ketchum recalled. Cayce had photographed the comet. Ketchum again: “He brought it down and showed me. It was Halley’s Comet, all right!” (Christian County, Kentucky, where Edgar Cayce was born 140 years ago, holds a festival every year commemorating an alleged UFO sighting; the tiny town of Hopkinsville, where Cayce is buried, was the site of the greatest point of the 2017 total solar eclipse.)

In his early twenties, Cayce fell sick and lost his voice. For at least nine months he remained unable to speak above a whisper. If nothing else this saved him from the life of a salesman; previously, he was peddling stationery products and also helping his father sell insurance for the Woodmen of the World company. A local photography studio took him on as an apprentice—the perpetually laryngitic Cayce made portraits of babies and families and brides and grooms; he photographed parades and store openings. Once a woman asked him to make a picture of the room in which her son had died.

Cayce would go on to have several photography studios of his own, in Kentucky and later in Alabama. One afternoon at A.R.E., Jessica Newell, archivist at the Edgar Cayce Foundation, loaned me a pair of gloves and allowed me to look through several boxes of Cayce’s photographs— of his wife Gertrude, with her fantastically upswept hair, of their children, especially the perpetually ecstatic baby Hugh Lynn; of Cayce himself, horsing around with a friend, once in drag. At least two of Cayce’s studios burned, so regrettably many of his pictures are long gone. I would have liked to have known him better as a photographer—to see if he read people through a lens as well as he did with his eyes closed.

When months had gone by and his voice had not returned, Cayce went to see a traveling hypnotist who was a recurring visitor to Holland’s Opera House in Hopkinsville. Everyone in town turned out to see Hart the Laugh King. There was wicked fun in watching the Laugh King lure your neighbors onstage, lull them into a somnambulist, unwitting state, and make them do turn-of-the-century pranks: climb imaginary ladders, play hopscotch, imitate fish. Backstage—for a fee—the Laugh King agreed to hypnotize Cayce out of his extreme hoarseness but his powers of speech disappeared when he woke up. Eventually Cayce cured himself: In March 1901, he lay down on the family couch, a horsehair sofa inherited from his grandparents, fell asleep, and sleeptalked himself through his own cure; when he woke, his voice had returned.

Unlike Hart the Laugh King, the sleeping prophet didn’t have to be a traveling showman, though he did move around the country a bit before a vision came to him of a permanent healing facility in a little town on the coast of Virginia. Embedded in his sleep readings was the advice that one should sleep facing east, and close to water, if possible. Construction on a hospital in Virginia Beach broke ground in the summer of 1928.

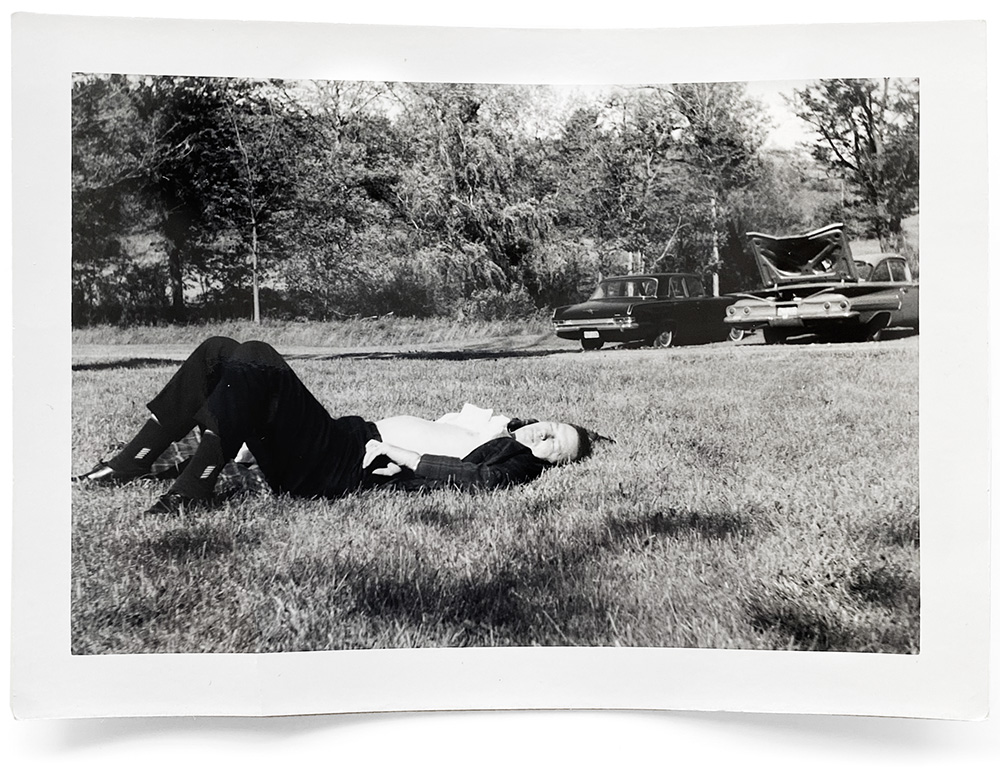

*

The blue Sears couch on which Edgar Cayce gave more than 14,000 readings is set against the north wall of the library, cordoned off by a dark velvet rope, reupholstered since the last time Cayce slept there, more than 75 years ago. A normal day meant a reading in mid-morning and one in mid-afternoon; for non-sleeping prophets, Edgar also advised twice-daily meditation, fifteen minutes at a stretch. Near the end of his life, when requests for readings flooded in, he upped this number considerably. The photograph above is of Edgar sleeping in his own bed.

Before giving a reading, Edgar would remove his coat and shoes, loosen his tie, and pray. He covered his eyes with his hands until he saw a little white light, and then he would seek the body of the person for whom he was reading, a tour guide Cheyenne tells us. When he had “found” them, he moved his hands to his solar plexus, and, from somewhere within his slumber, the reading would begin.

What is the true sound of the sleeping prophet? Added over some early footage of the A.R.E., an obvious voiceover transforms the Kentucky-born Cayce into a television Southerner but in a rare publicly available audio clip from a reading, a sleepy-sounding Edgar intones a cryptic recipe involving castor oil and cervical application—”just what the body will absorb, see?”

Almost always Gertrude, his wife, and Gladys Davis Turner, his resident stenographer, were present. Gertrude conducted the readings, prodding Edgar with questions from the seeker, and Gladys scribbled it all down in her steno notebooks. When Edgar woke, he claimed not to remember what he had spoken, or even, sometimes, to know the meanings of the medical terms he gave. Afterward, Gladys typed up her notes into lengthy and detailed readings, one copy for the seeker, and one for the archives. Her sleep-talk translations, her notes and summaries and transcripts of the readings are cross-categorized—bound brown notebooks like law depositions, in typed notes stored in card catalogs, “like libraries in the eighties,” Cheyenne says. More copies are shelved in notebooks by subject (Sin, Sleep, Smiles), and stashed in drawers divided between Spiritual and Medical topics—Edgar would point his body north for the latter, south for the former.

*

On January 3, 1945, the prophet died in his sleep. For years after, people continued to write to Gladys, usually to ask her for copies of their readings. Stored in one of the notebooks is a blurry copy of a postcard of the Great Sphinx and a handwritten message on the back, dated 1980, presumably a past-lives inside joke: Am still trying straighten out all that trouble you caused here just by coming into the world : )

All is going nicely but slowly as is natural here.

Just as she had documented the sleeping prophet’s words, Gladys duly recorded the succinct response she mailed back: I know it Honey and I’m trying to help you.

*

Gladys and Gertrude who were often the only witnesses of the readings, and, looking at Edgar’s blue Sears couch and their absent chairs, it was the two of them I thought about most, the invisible two-thirds of this little band, this strange collaborative trio: the prophet, the conductor, the writer. There is room only for one on the narrow sofa but Gladys’ scratched-up and weathered wooden desk rests closest to the pillow, the better to listen.

Dear Lester: Crushed Greystone? & An Assignment

Dear Lester: In one of my most memorable dreams I found myself on a bright orange beach – a few other identityless others were there, but I was not interacting with them – it felt as if we were there together, each individually exploring the environment. I crouched down, scooped up some of the bright orange sand in my left hand and then watched it pour out from between my fingers. I said to myself, out loud in the dream, “crushed greystone – I dont get it”, and then I woke up. What does this mean? Quandrously yours, B.

Dear B: Greystone was the psychiatric hospital where Woody Guthrie was hospitalized from 1956 to 1961 (his Huntington’s disease was misdiagnosed as schizophrenia.) His second wife Marjorie would visit him on Sundays with their children: Arlo, Joady and Nora. Their first child, Cathy, died in fire in 1947. In Ramblin’ Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie, Ed Cray writes about Guthrie’s response to her death:

There would be no funeral. Marjorie and Woody had the body cremated with the intention of scattering Cathy’s ashes along the Coney Island beach she loved. A day or two after Cathy’s death, Cisco Houston and Jim Longhi silently walked along that dark beach with Guthrie, bonded in grief. Guthrie suddenly threw himself on the sand, his arms and legs in the air, raging into the dark sky. “He screamed for thirty seconds,” Longhi recalled. “And then he got up. And it was over.”

To answer your question, crushed greystone is incomprehensible grief and illness. To process these feelings I recommended listening to this song by Billy Bragg with lyrics by Woody Guthrie.

*

Dear Lester: I have struggled from severe depression for about two years now. I’m on my way back out of it now and am trying to rebuild my life. I am having trouble finding something to photograph or the urge (spark) to do anything more than maintain. I’m in therapy, I take medication, I’ve tried this and that. I’ve notice that I’m better at working on something when I have someone (something) to be responsible to. This gets me to my question, will you give me an assignment? It could be a life assignment or a photography assignment, whichever you prefer. Thank you, Rylan

Dear Rylan: Assignments are a great way to get out of a rut (hence this column). I looked you up and see that you live in Ohio. When Brad Zellar and Alec Soth worked there in 2012, they created a newspaper just so that they would have deadlines. In one of his Dispatch essays, Zellar wrote about a visit to a fraternal organization, Moose Lodge #393, in Clyde, Ohio. “I expected xenophobia and a desultory tableau of hard-bitten morning drinkers,” Zellar wrote, “What we encountered instead was a lively and welcoming group of characters who seemed genuinely pleased to have us there.”

My assignment for you is to find a club. It could be a fraternal organization like the Moose, or something different (Cuddle Party Columbus looks interesting.) You can think of this as a photo assignment if it gets you out the door, but it might end up being a life assignment. I believe Brad Zellar is still a member of Moose Lodge #393.

Do you need advice?

Creative or otherwise.

Email Lester: DearLester@LittleBrownMushroom.com

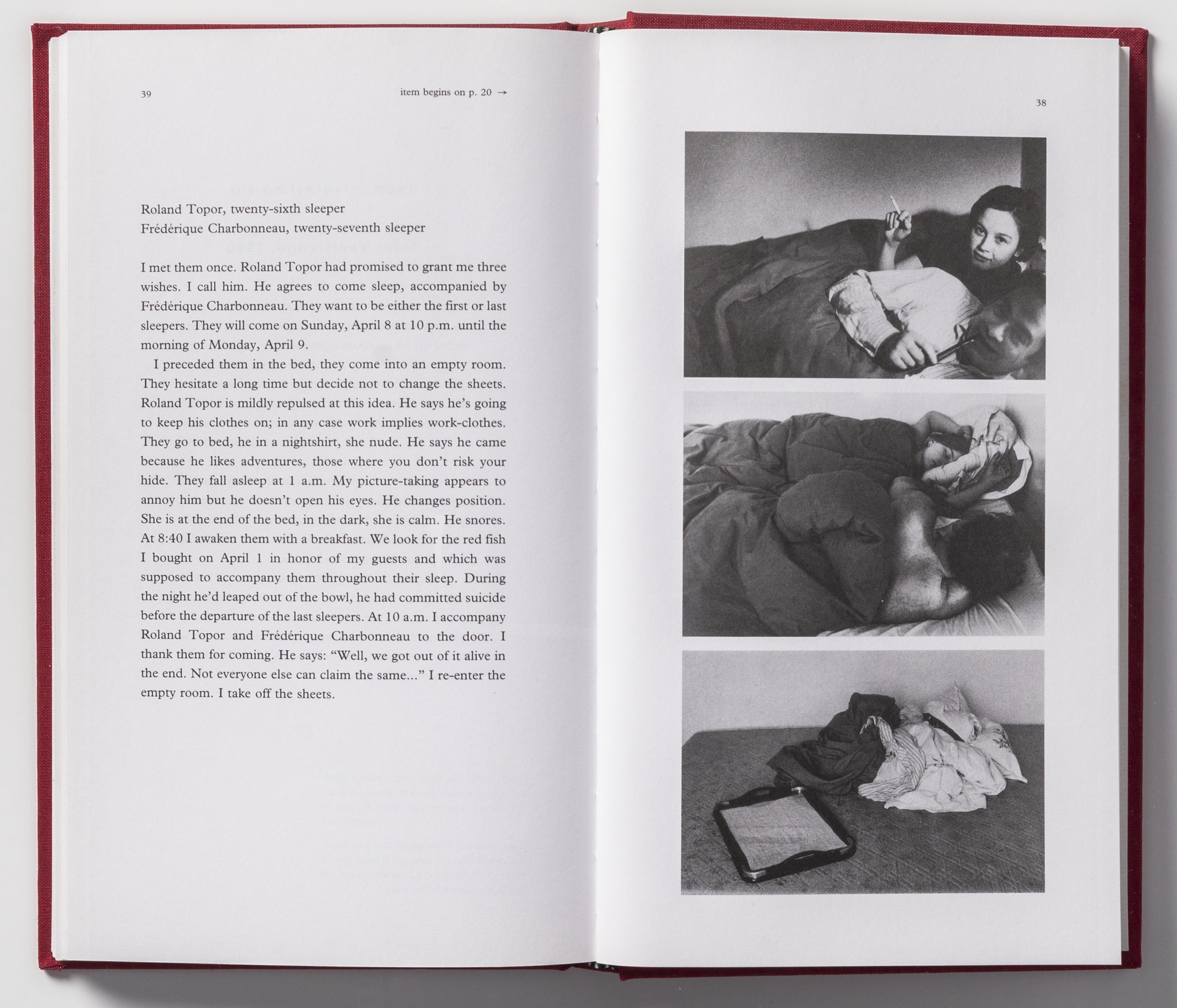

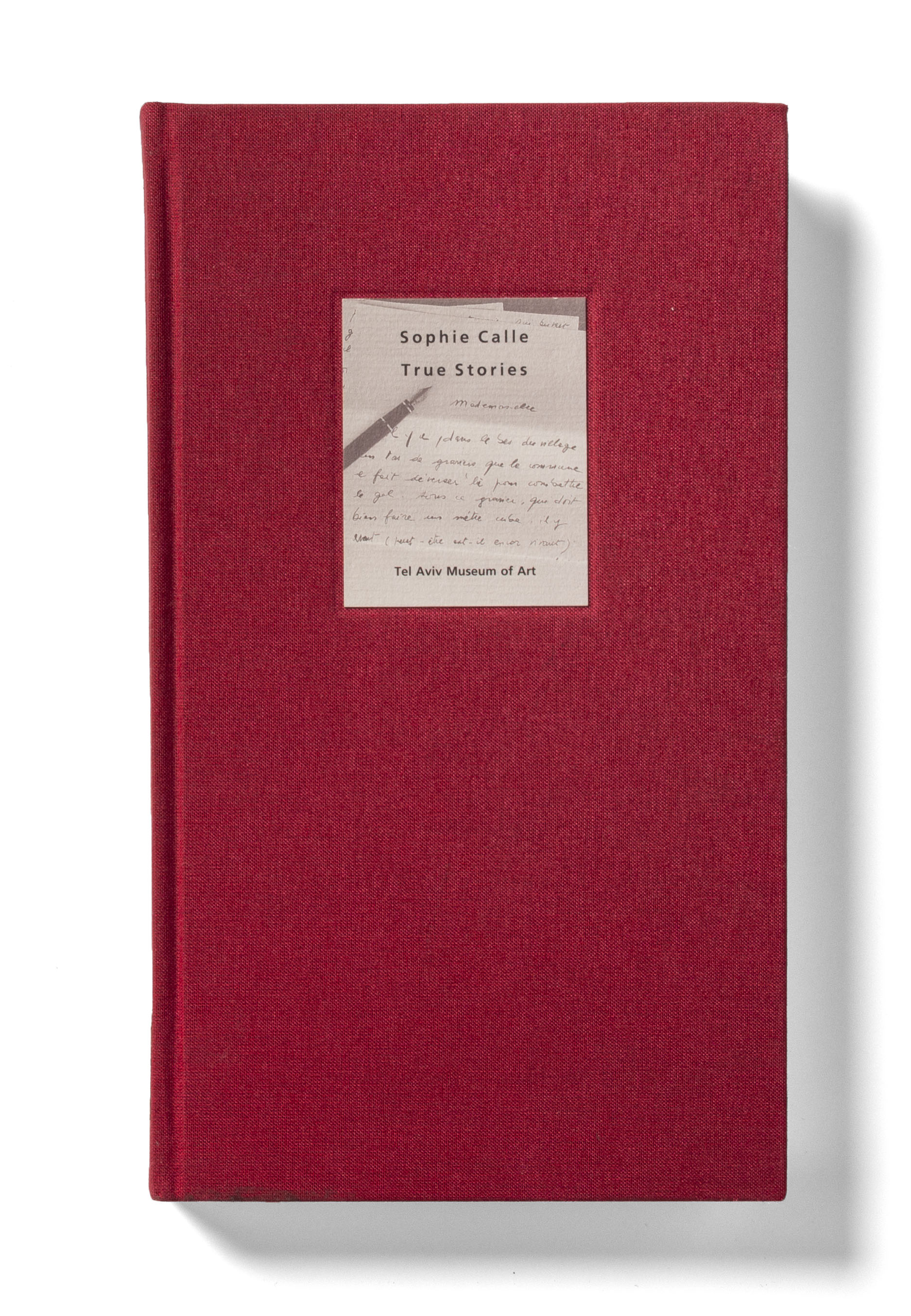

Ex-Libris: “The Sleepers” from True Stories by Sophie Calle

Sophie Calle doesn’t have a daily routine. Every day is different; except Sundays, which she spends in bed. I recently visited her on a Sunday in her hotel room in San Francisco with my daughter and a couple of friends. We sat around her bed while she told us about her beginnings as a photographer at the age of 25:

Whenever I traveled I played with what I would want to do. I was a waitress in New York. I worked on a farm in Mexico. And then, in Bolinas, I rented a room at the house of a photographer. I took photos in the graveyard. I printed the pictures and liked something in those photos. My father had always told me that the day I knew what I wanted to do he would help me. I called my father saying maybe I want to be a photographer. He said, “then I help you, come back to France.” I had to give something to my father for him to give me a roof. I had to pretend I was going to do something. And it worked. I started to take photos.

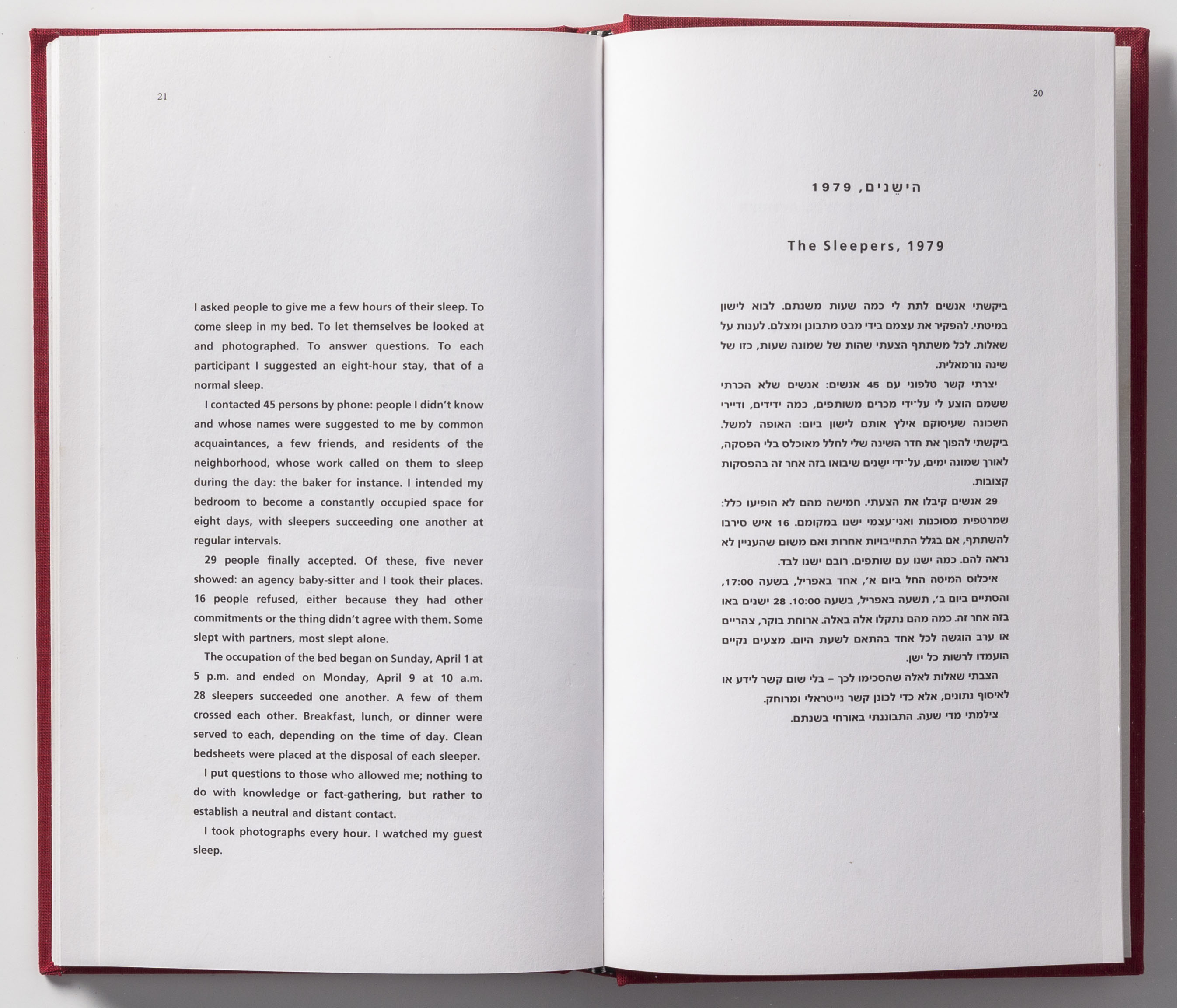

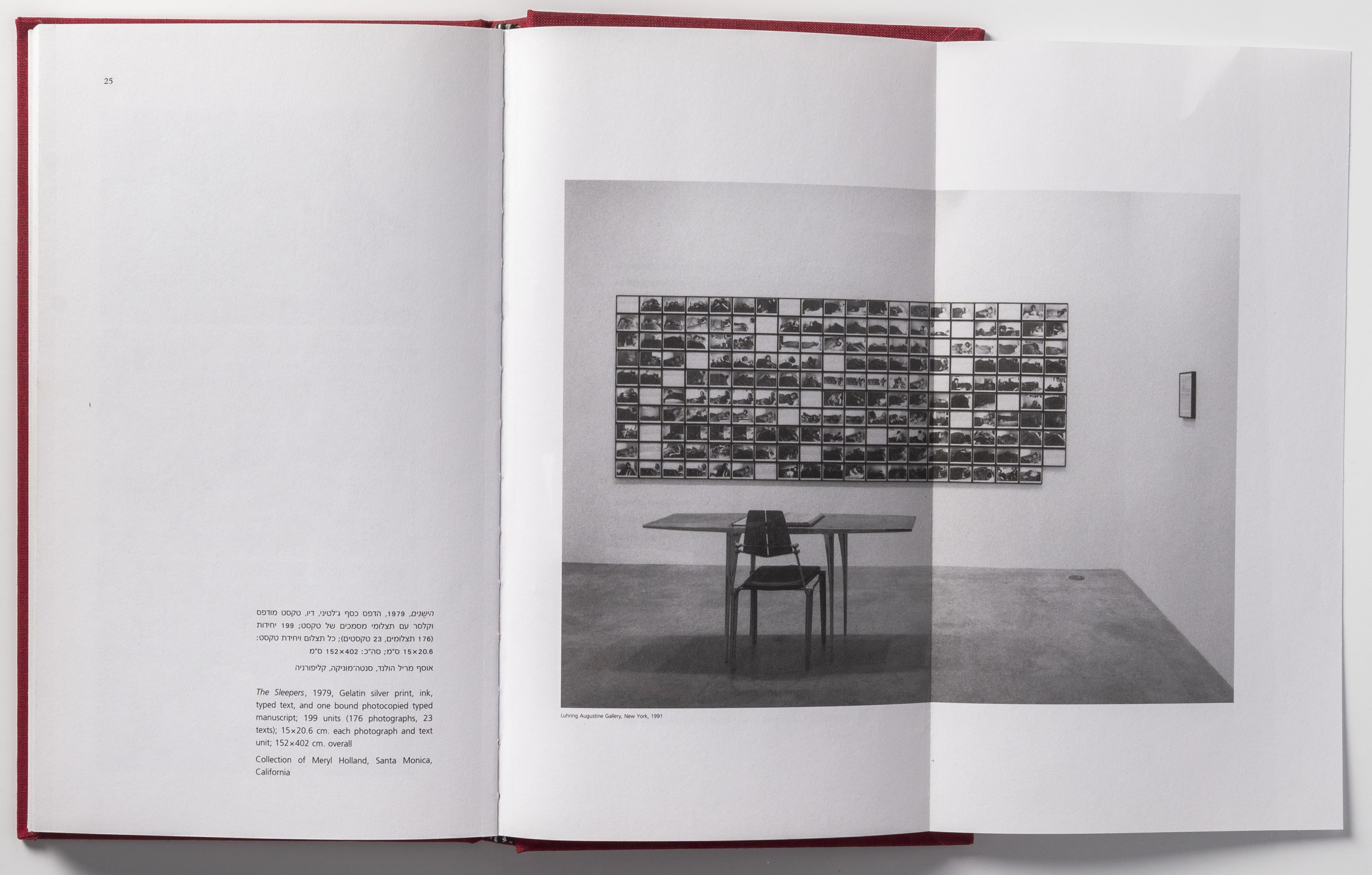

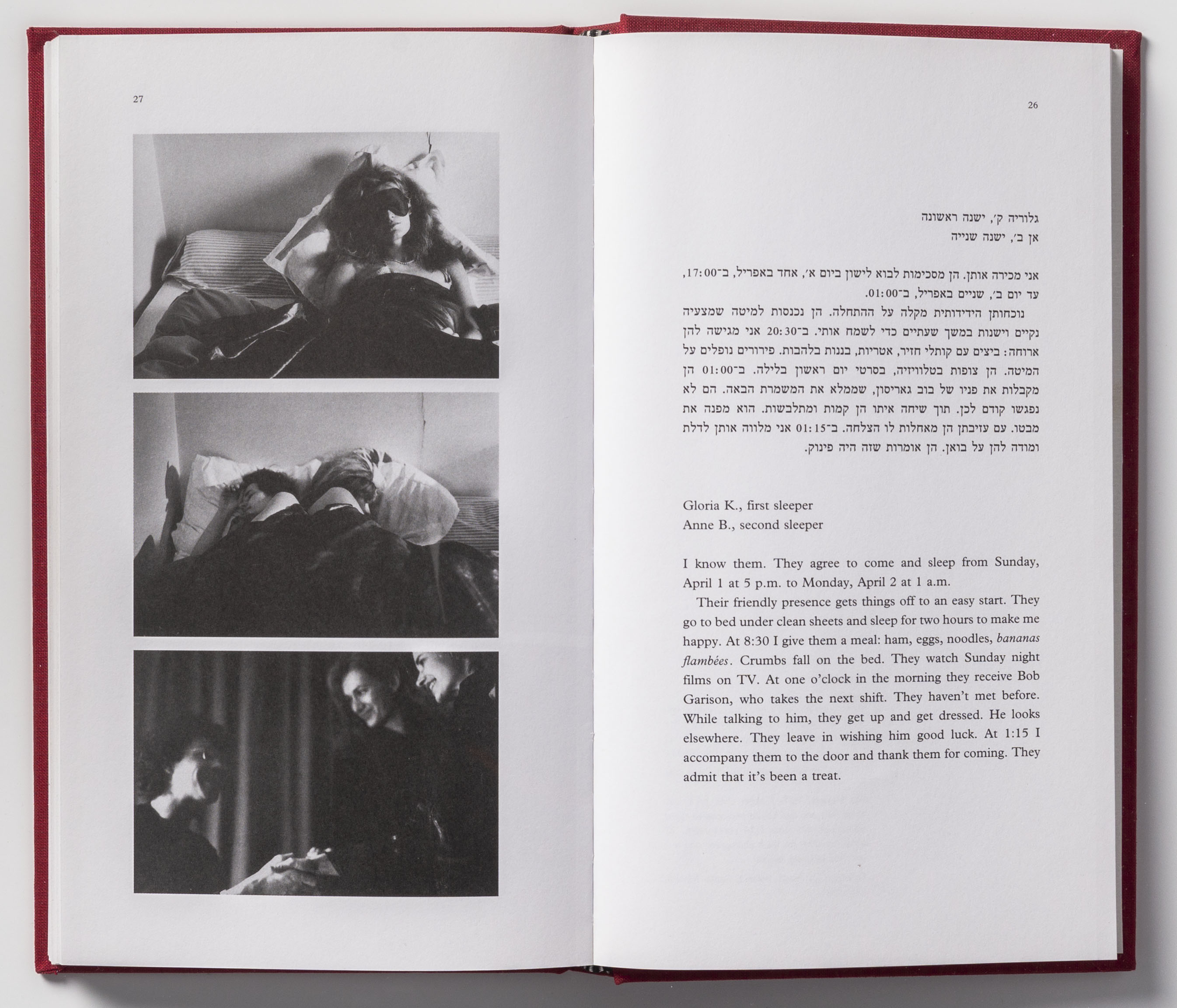

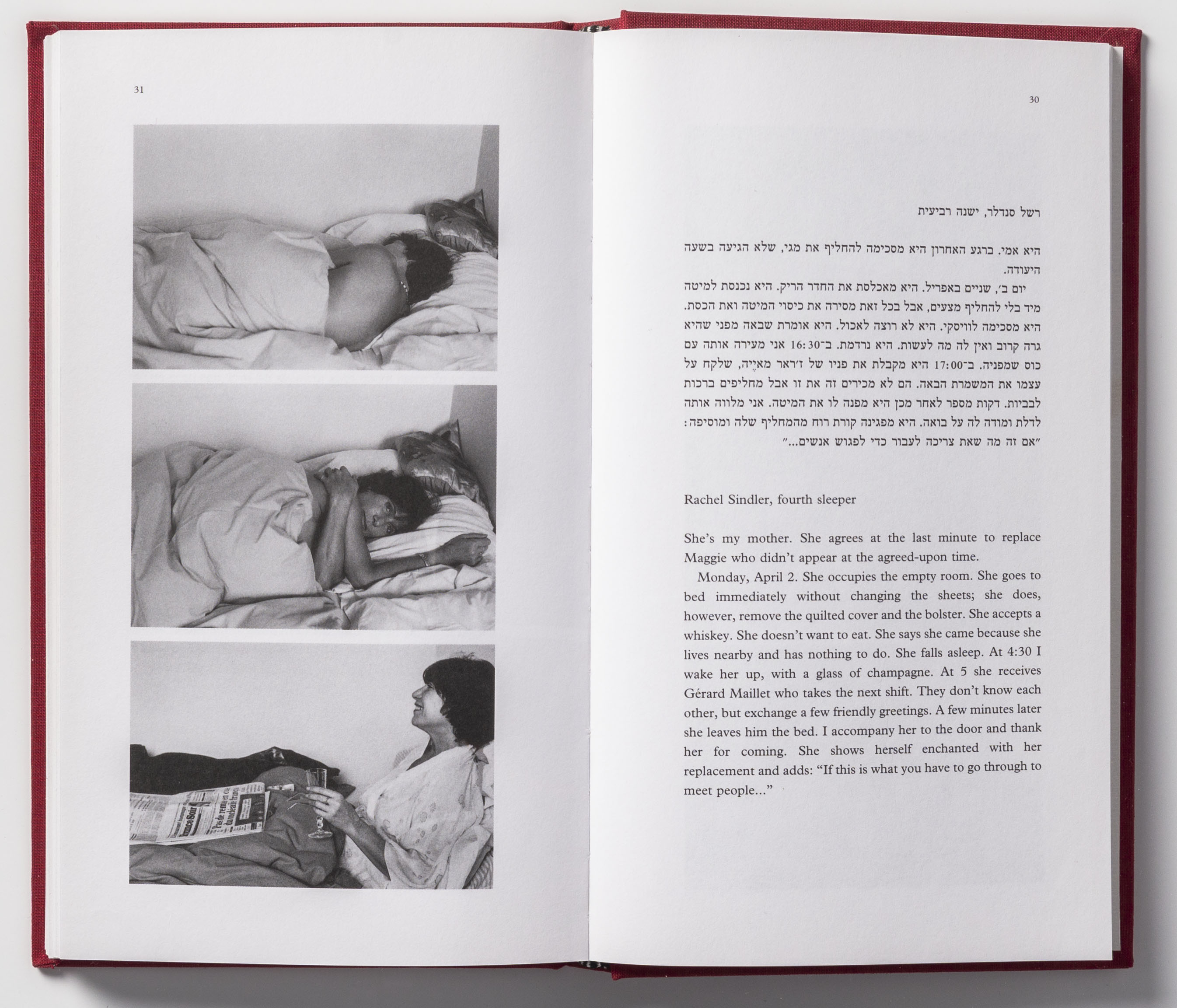

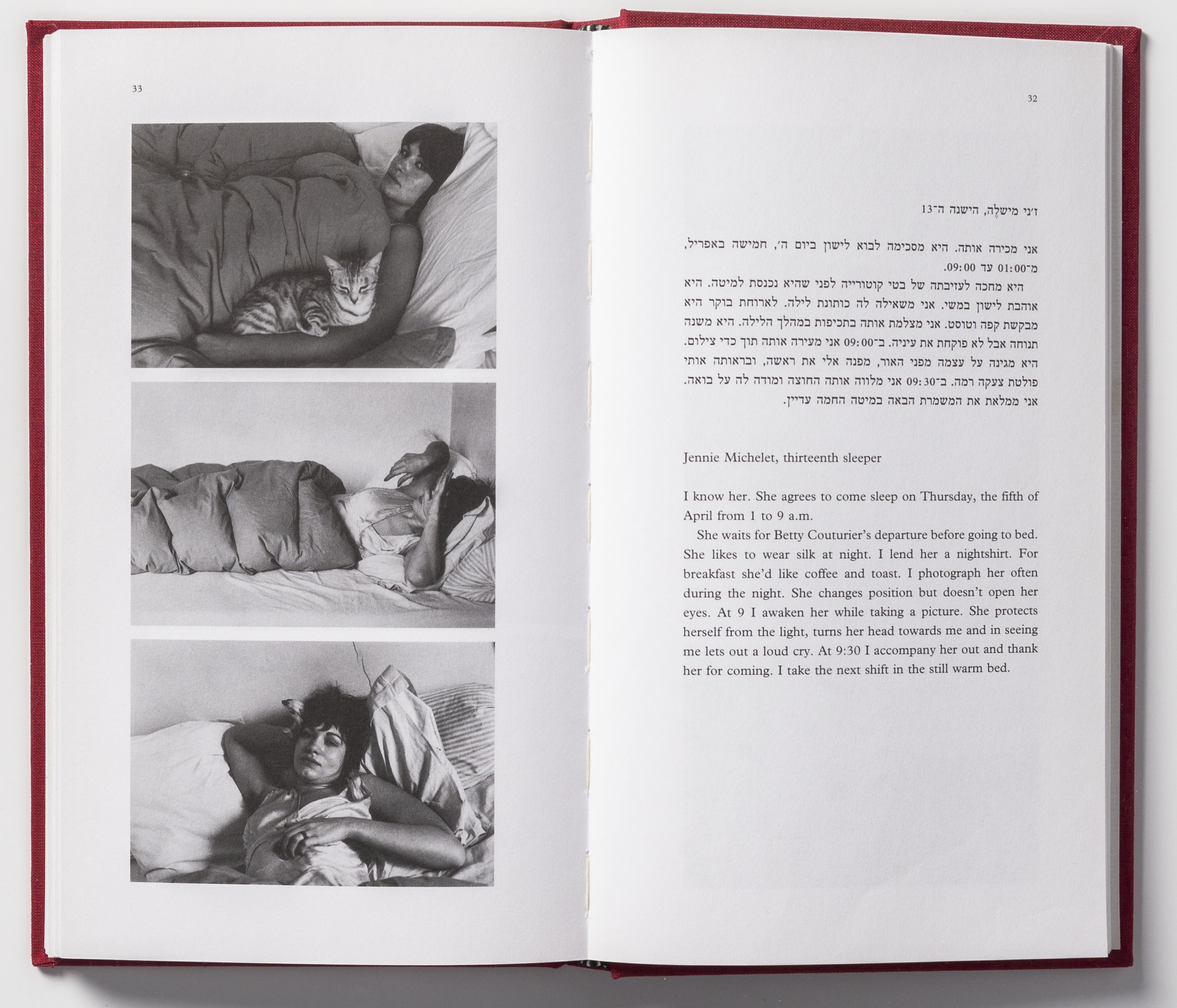

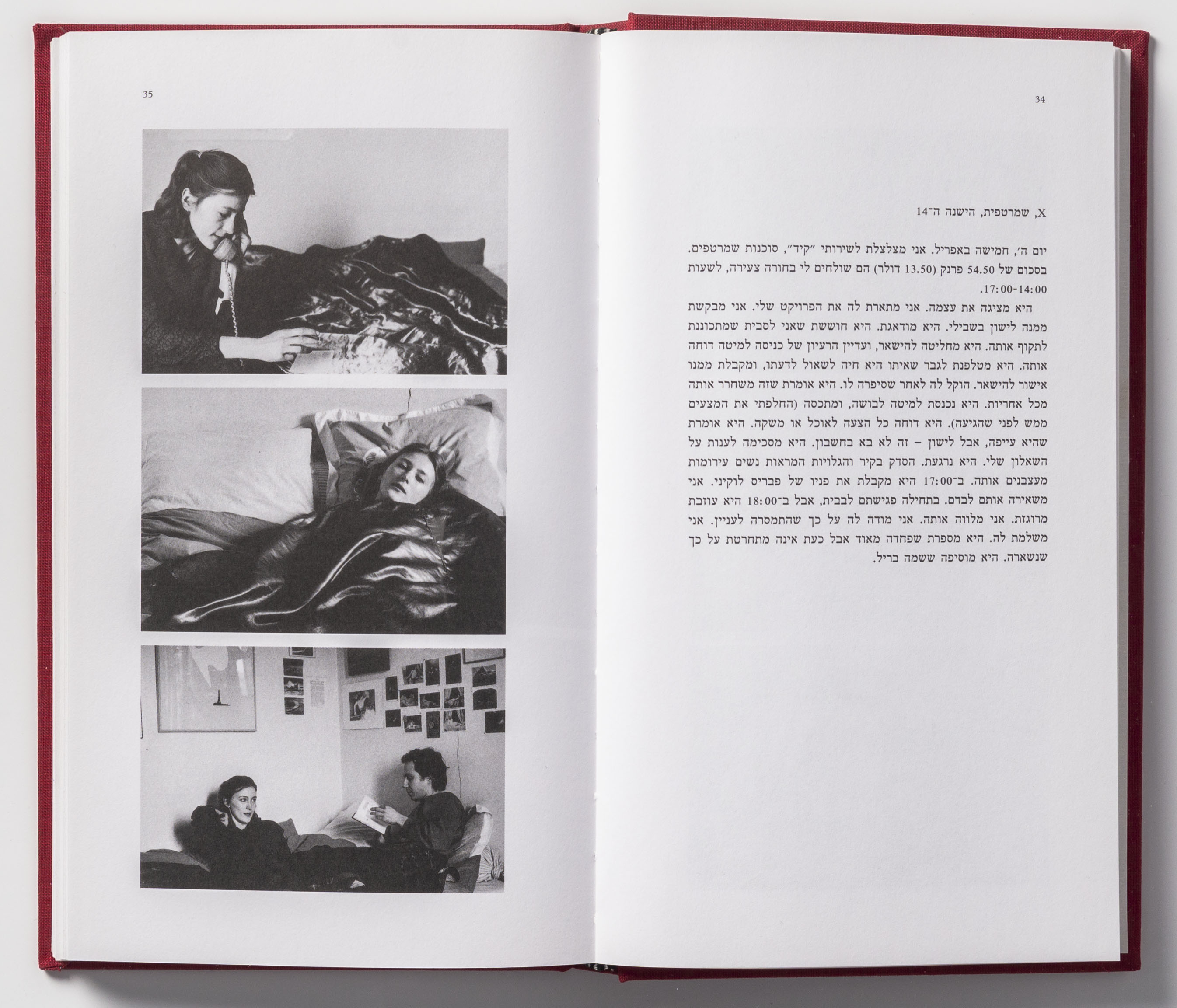

One year later, Calle completed her first project, The Sleepers, in which she invited friends and strangers to sleep in her bed. Calle photographed them every hour as they slept. My favorite of the 23 sleepers is Calle’s surprisingly young looking mother, Jennie Michelet. When she’s replaced at 5am by a male sleeper, her mother says, “If this is what you have to go through to meet people…”

I’ve only been able to find a stand-alone version of this work in French, Les Dormeurs, but it’s reproduced in a number of her English books. My favorite is in the catalog for True Stories at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.

See The SleepersHERE

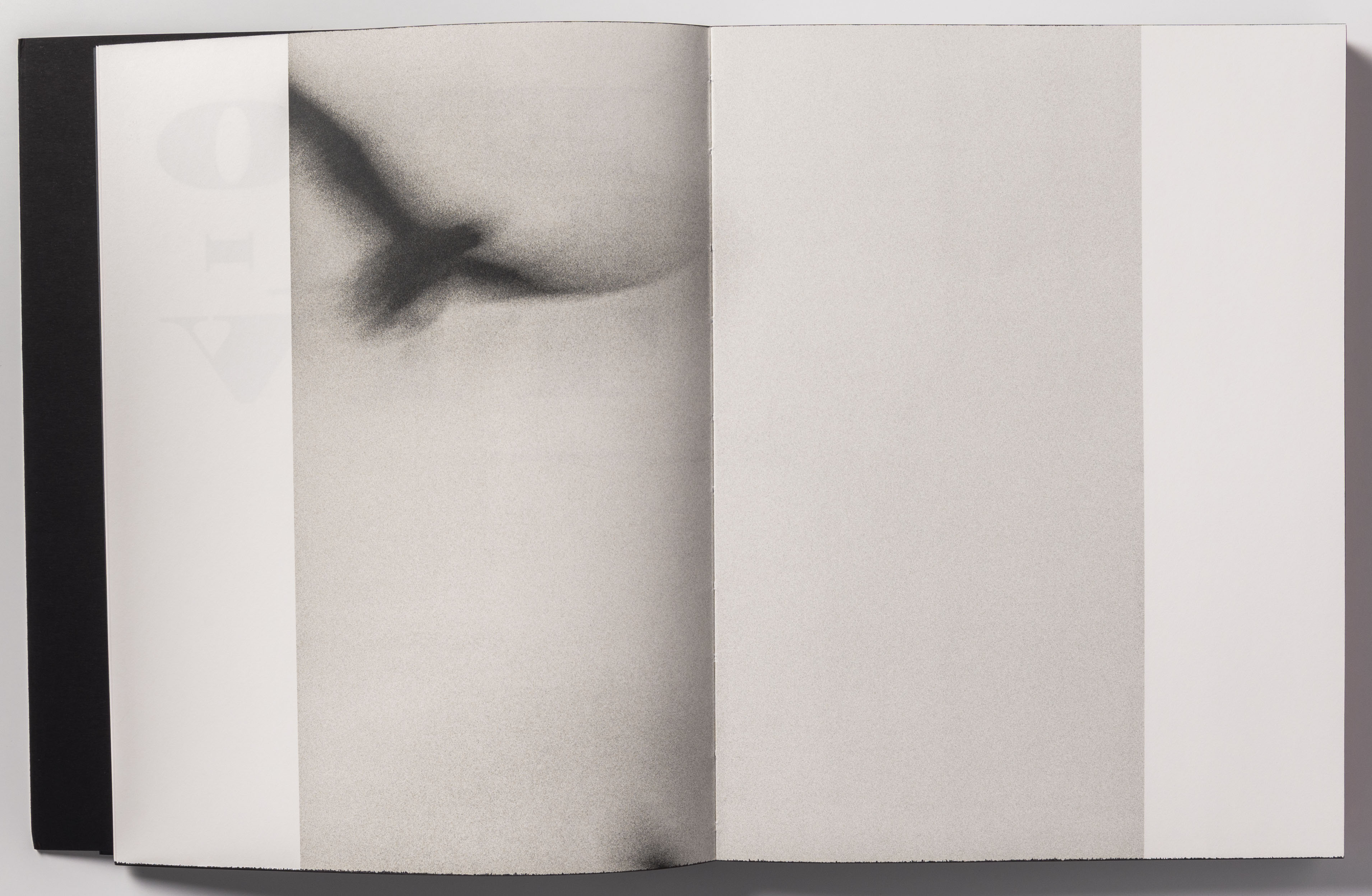

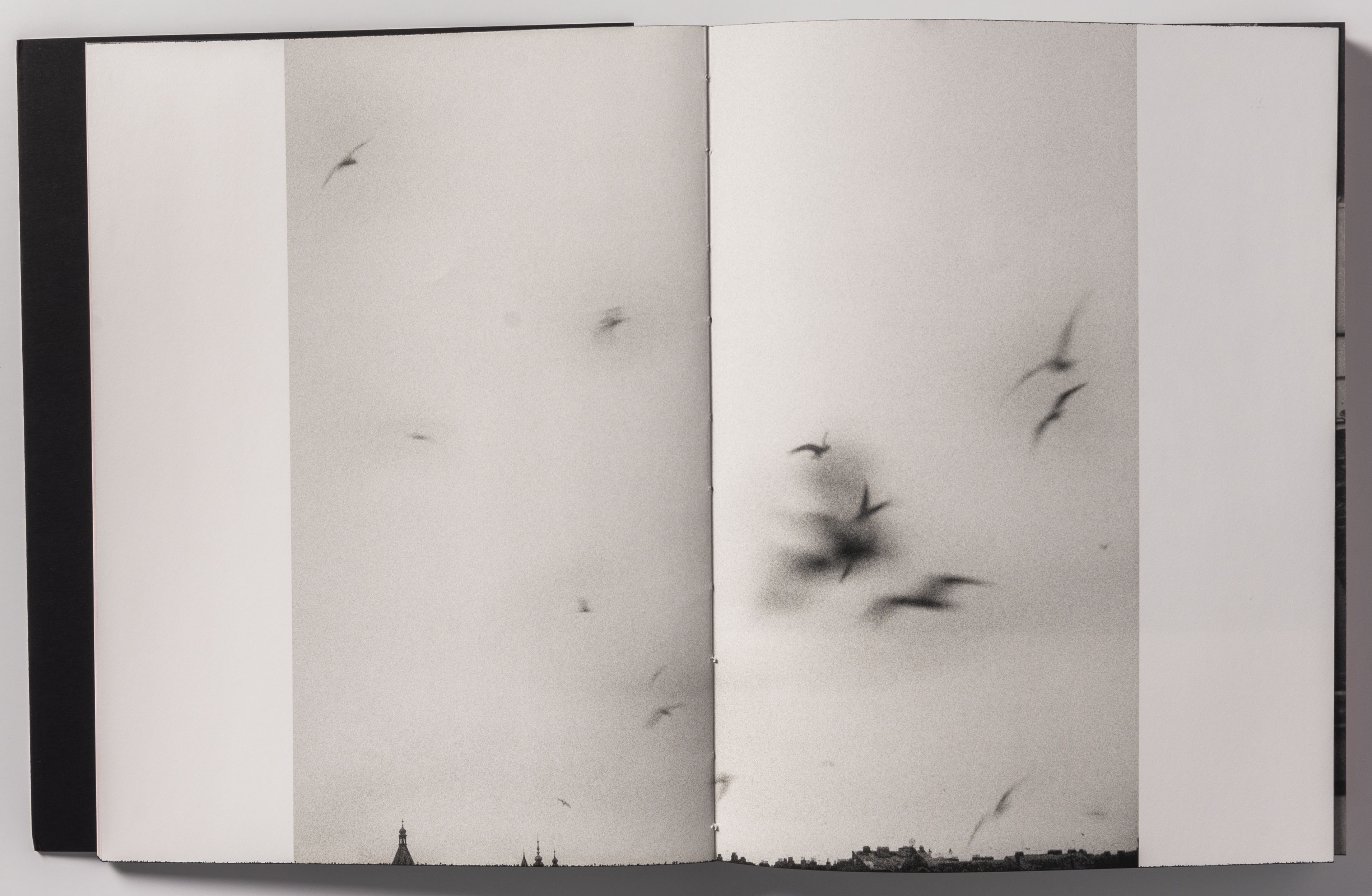

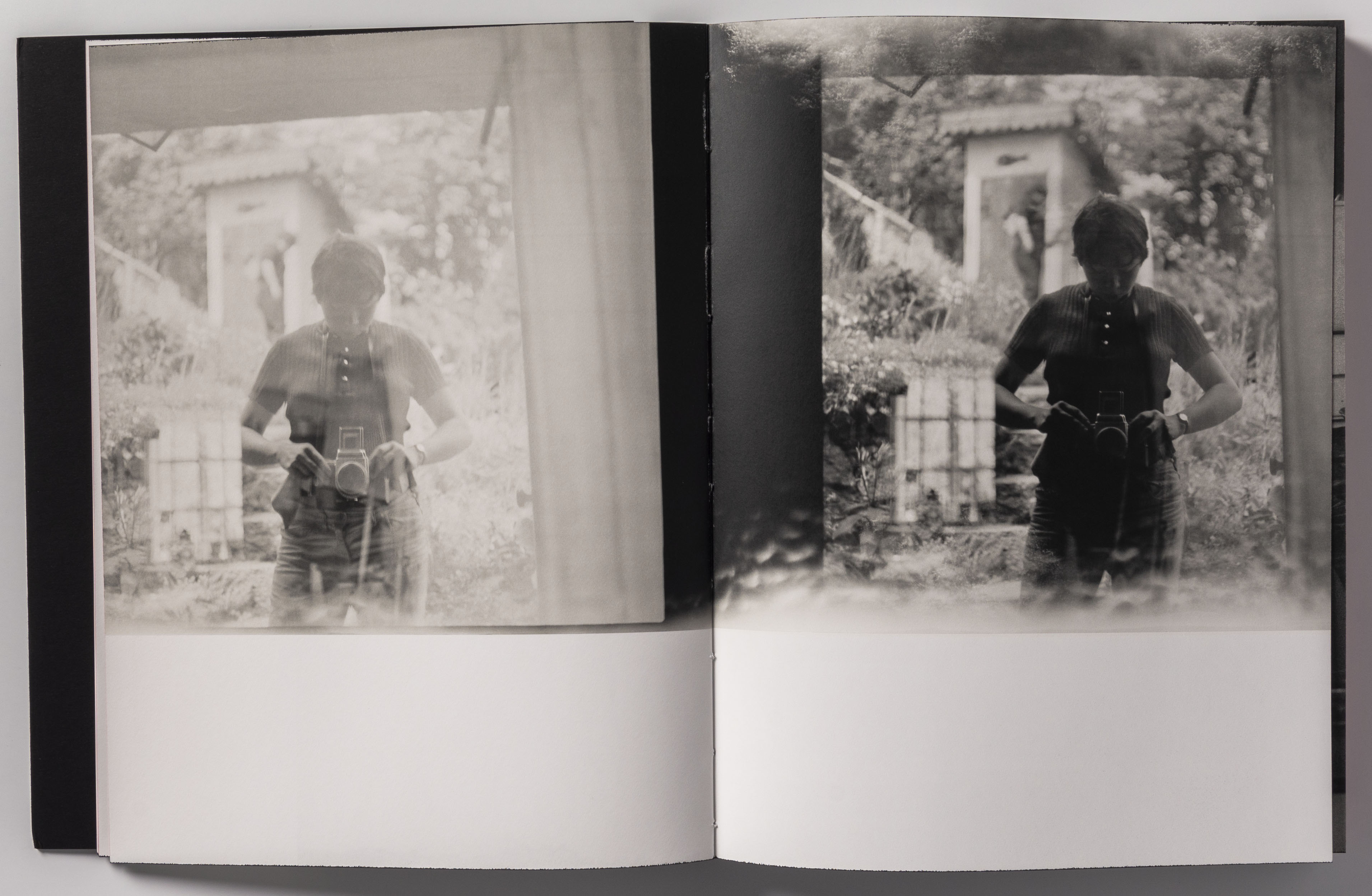

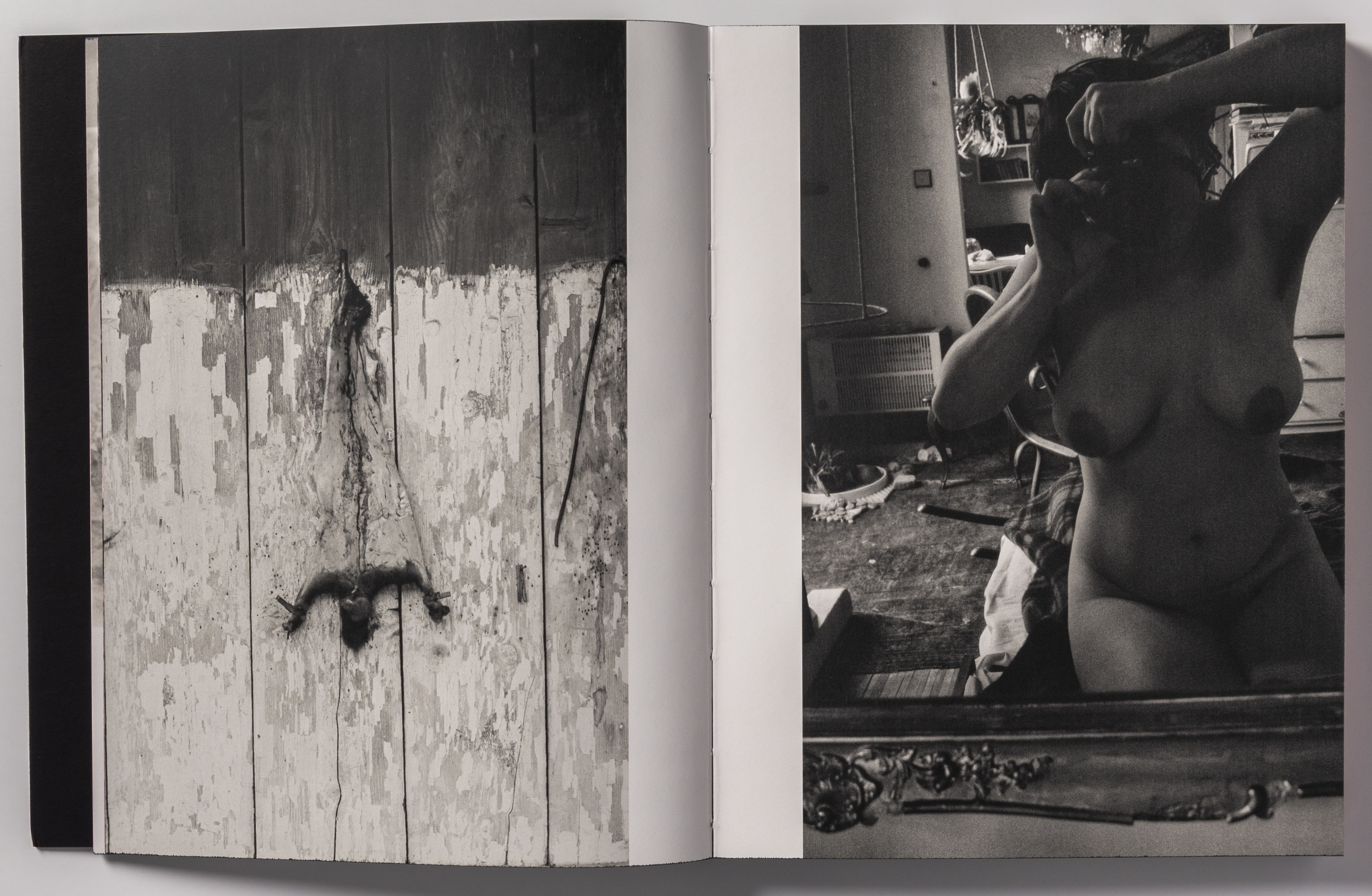

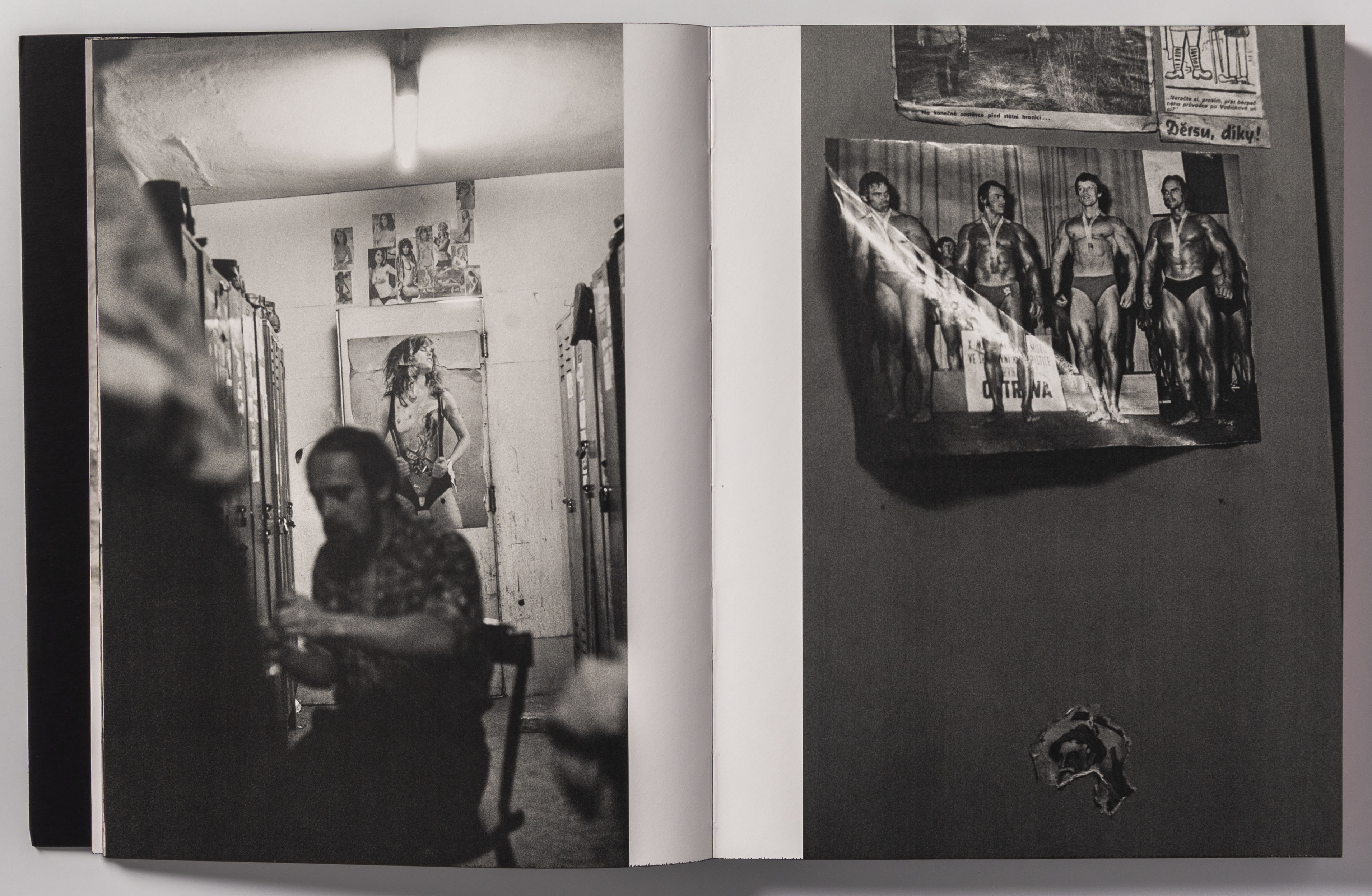

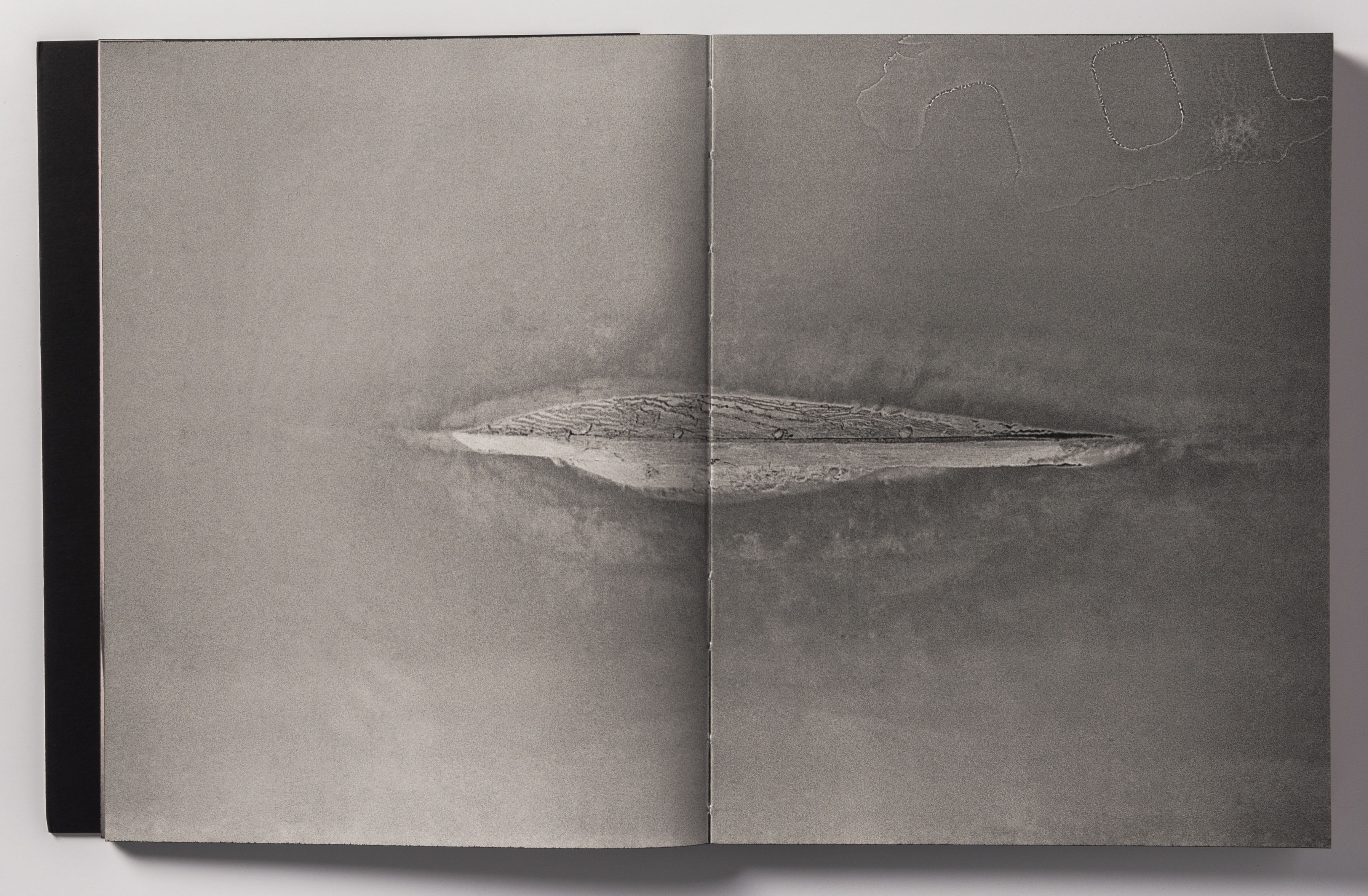

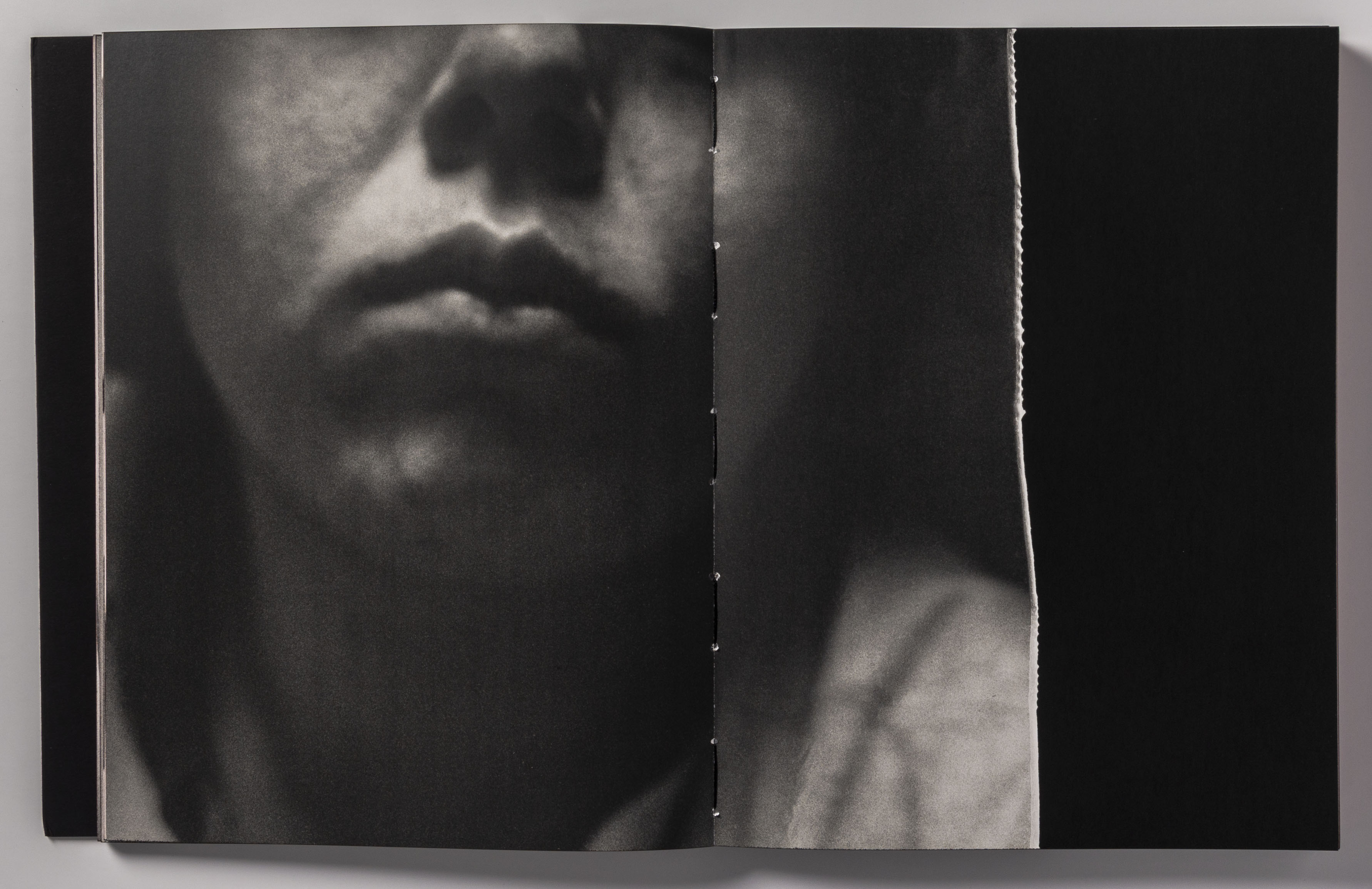

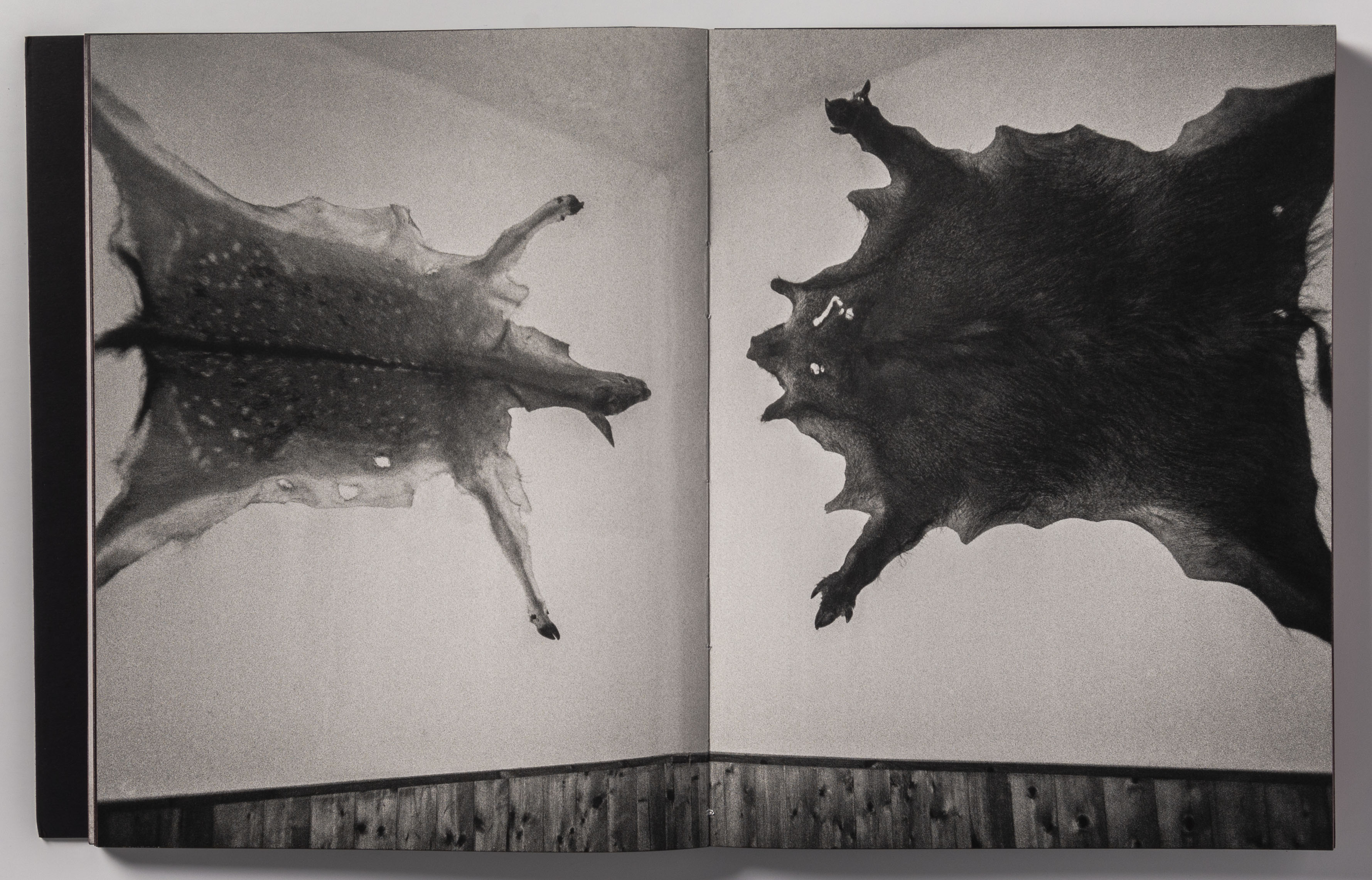

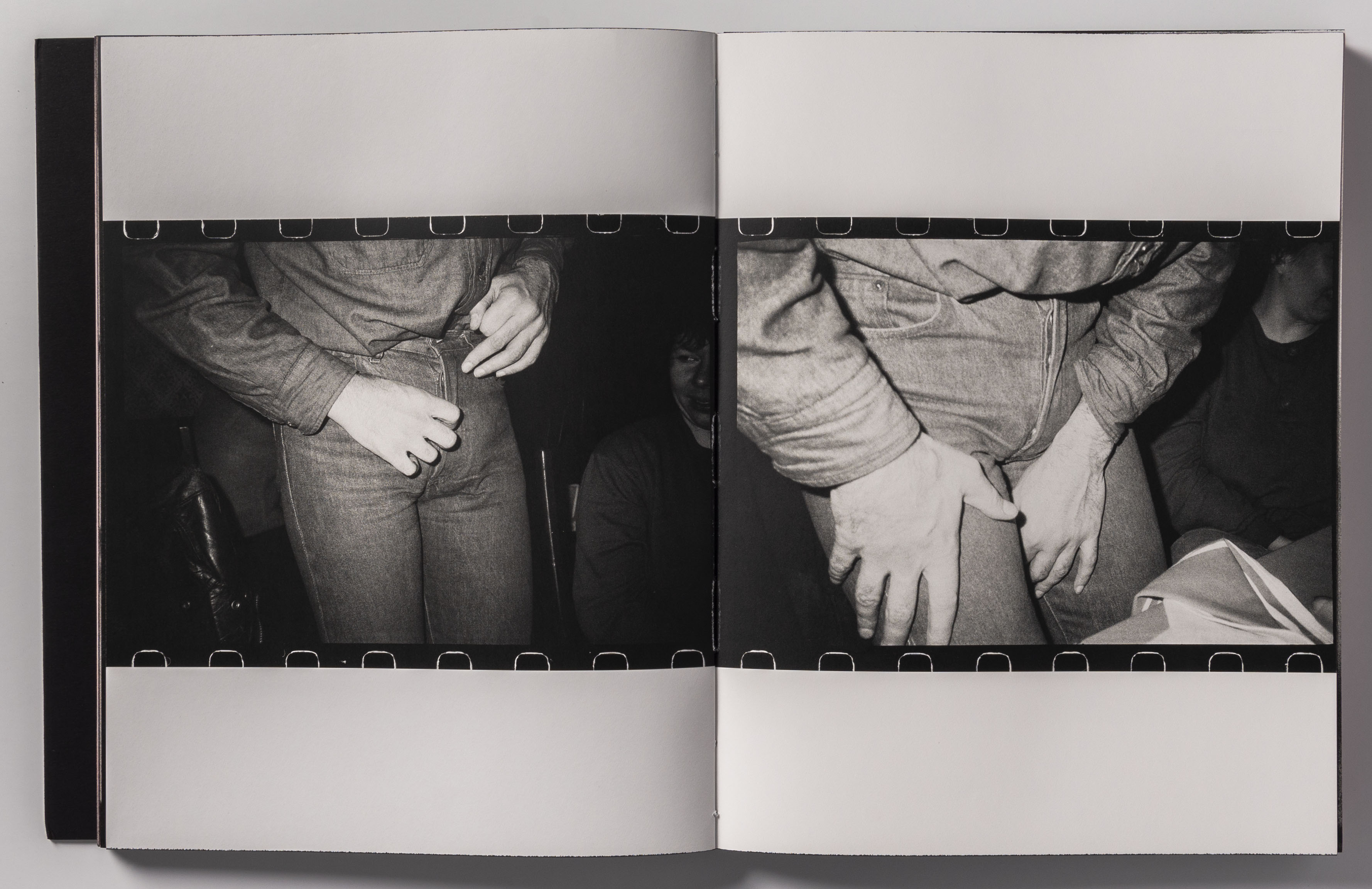

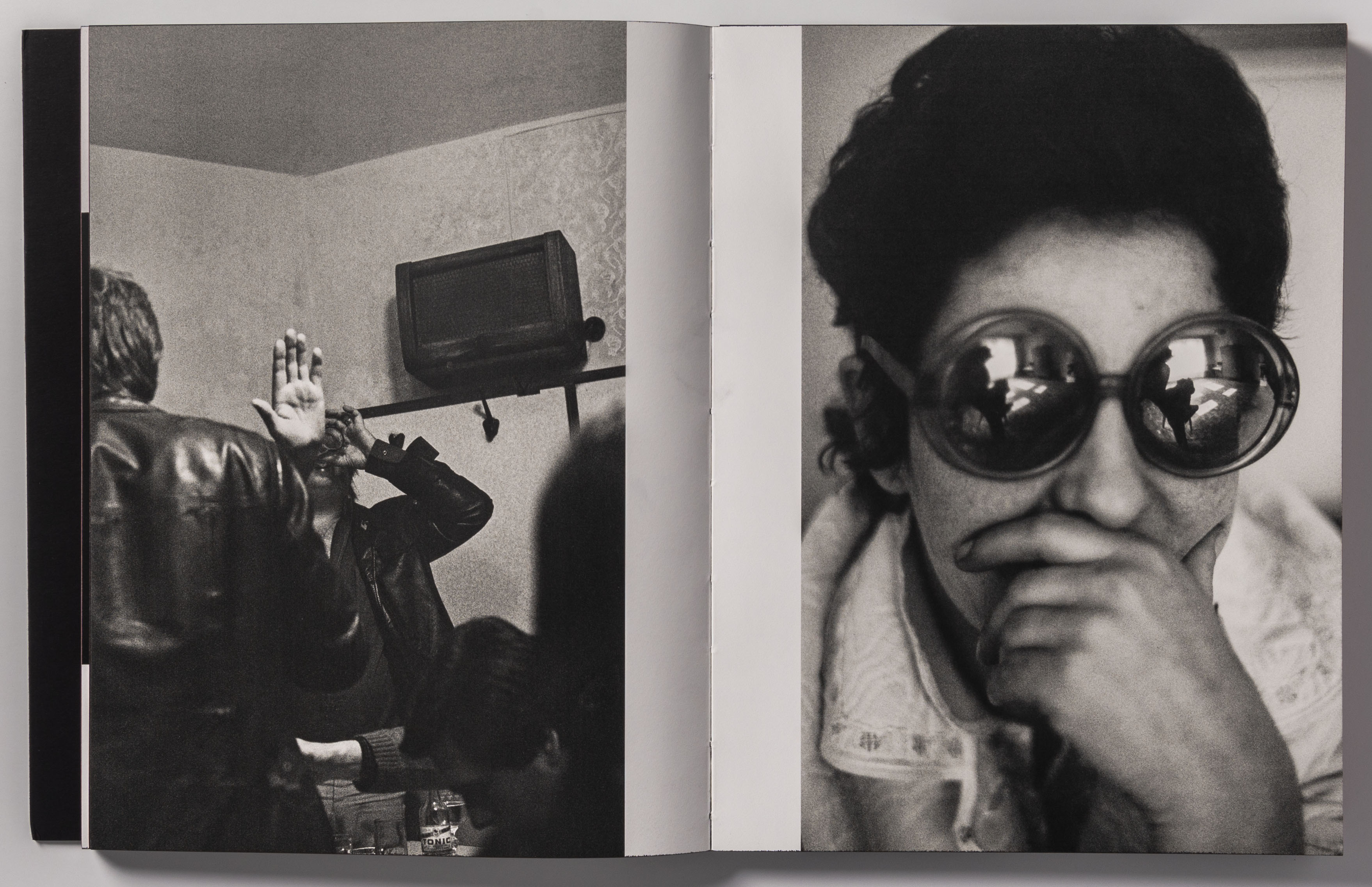

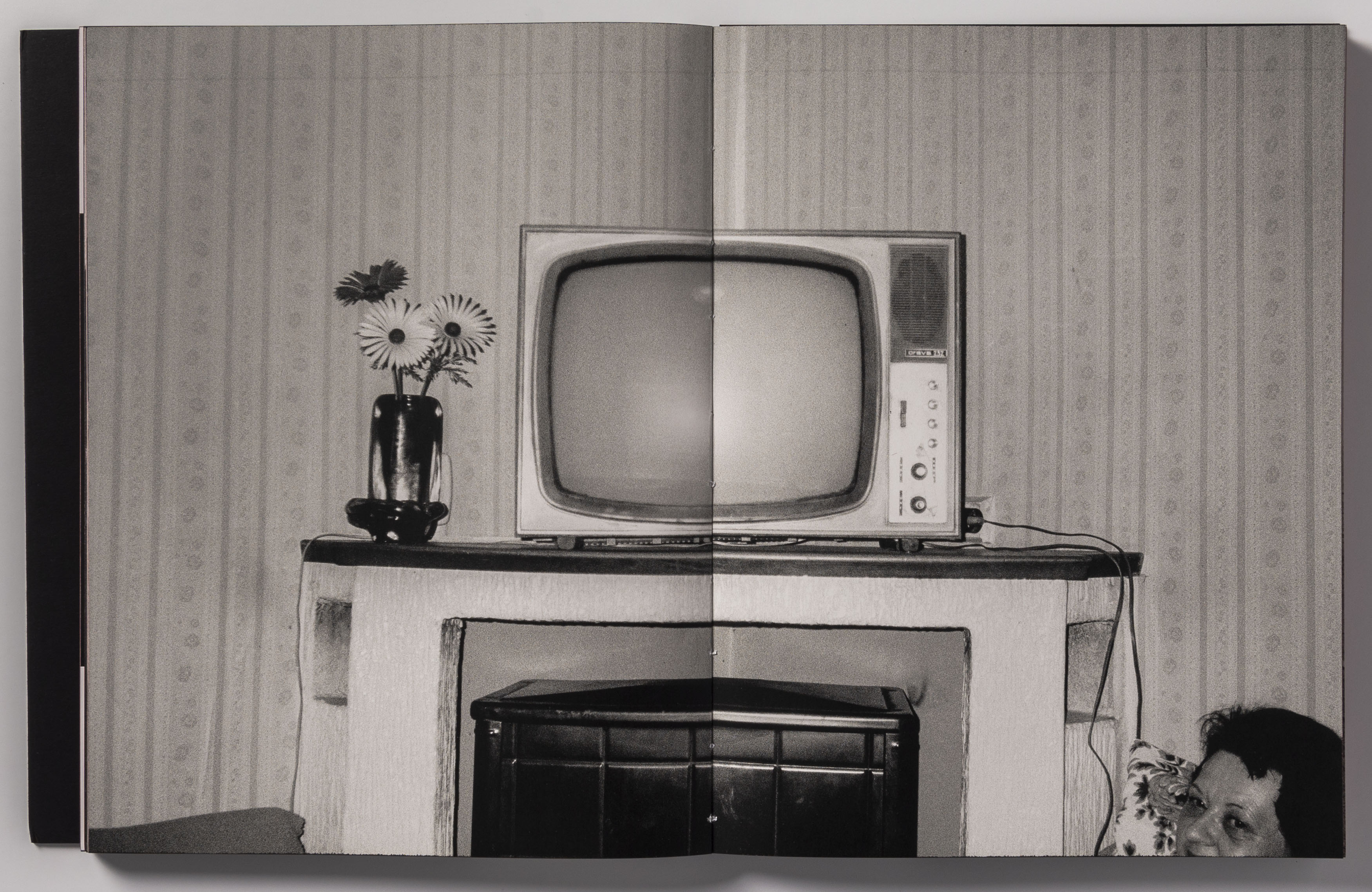

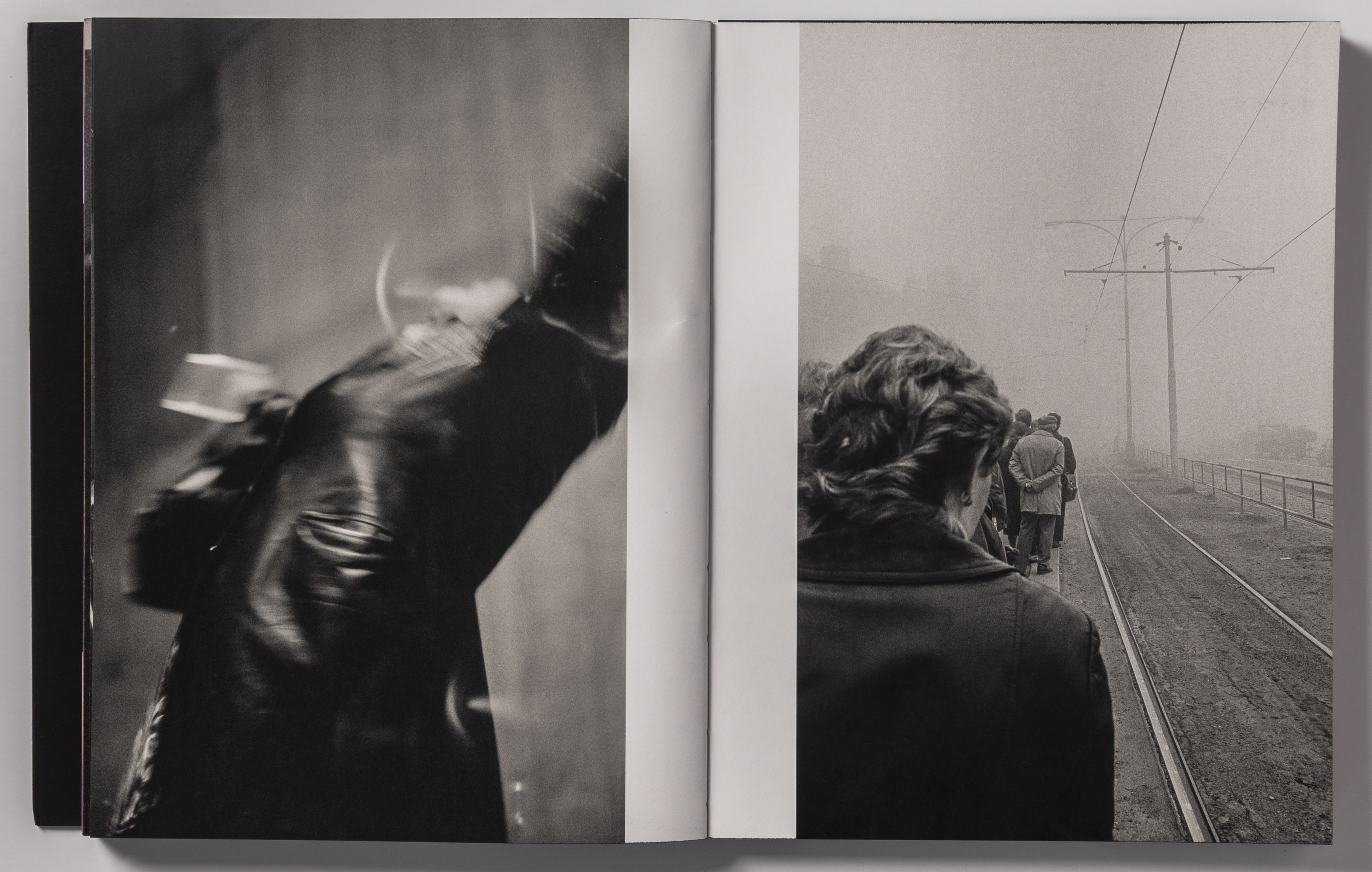

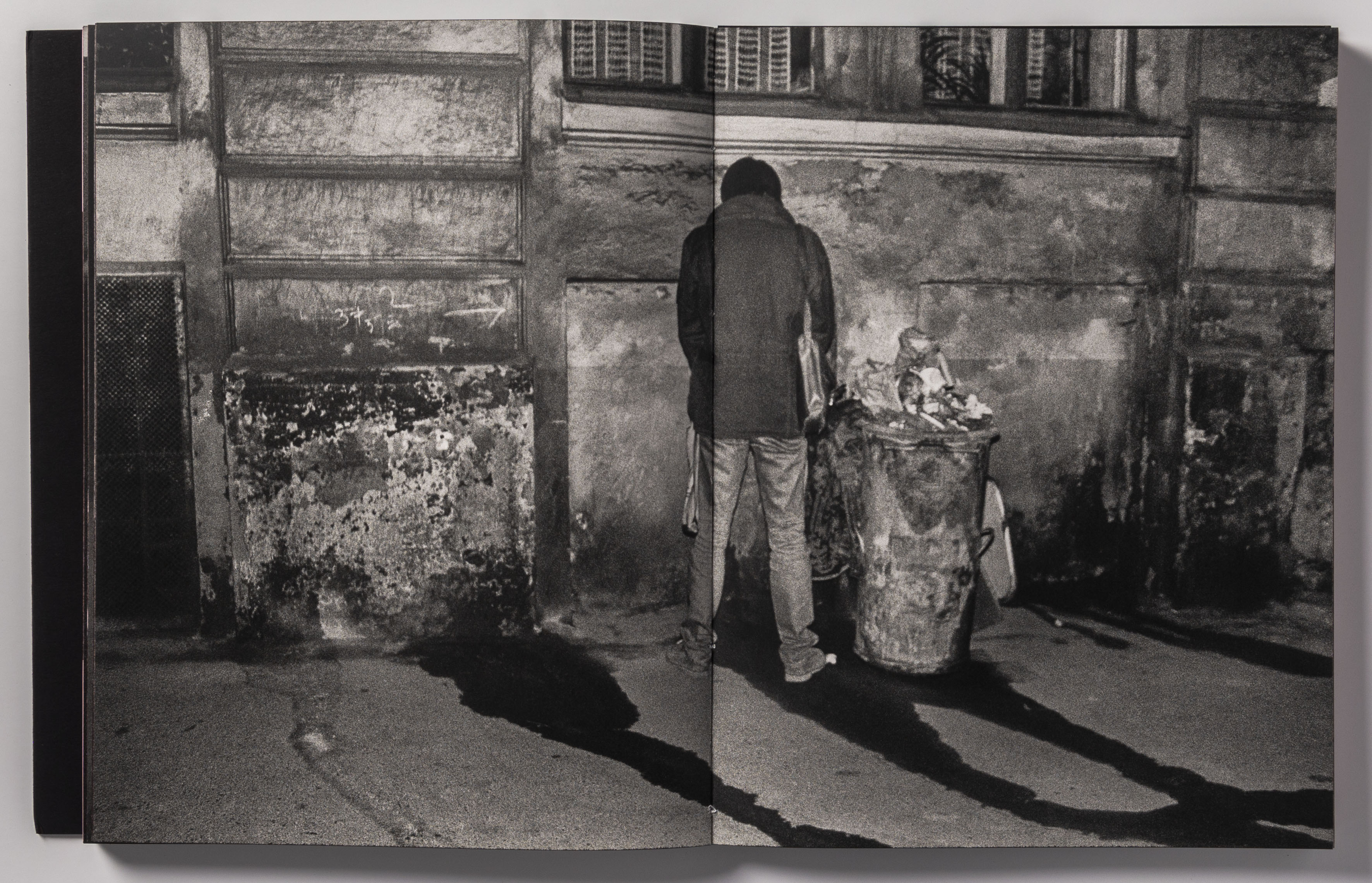

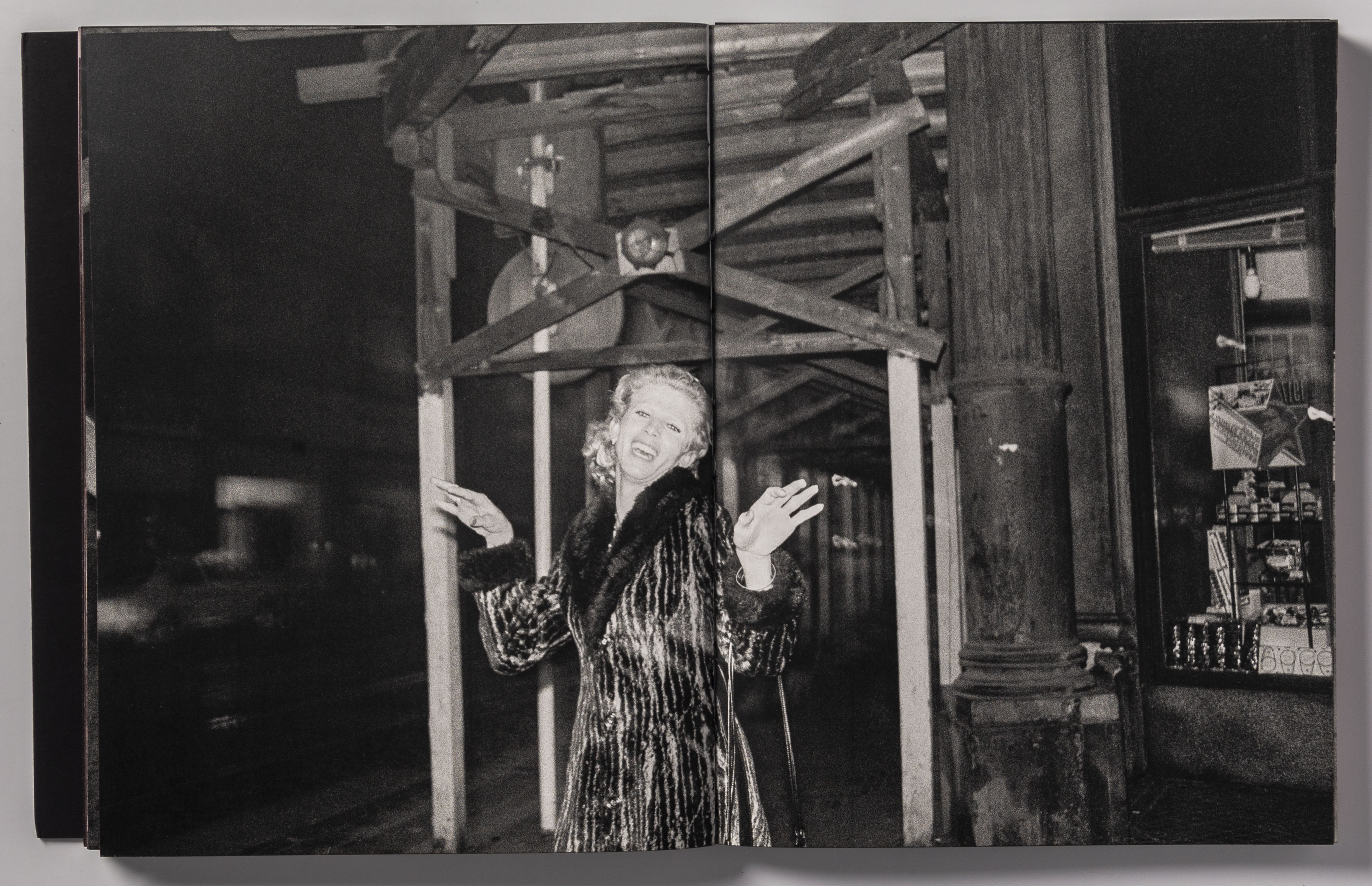

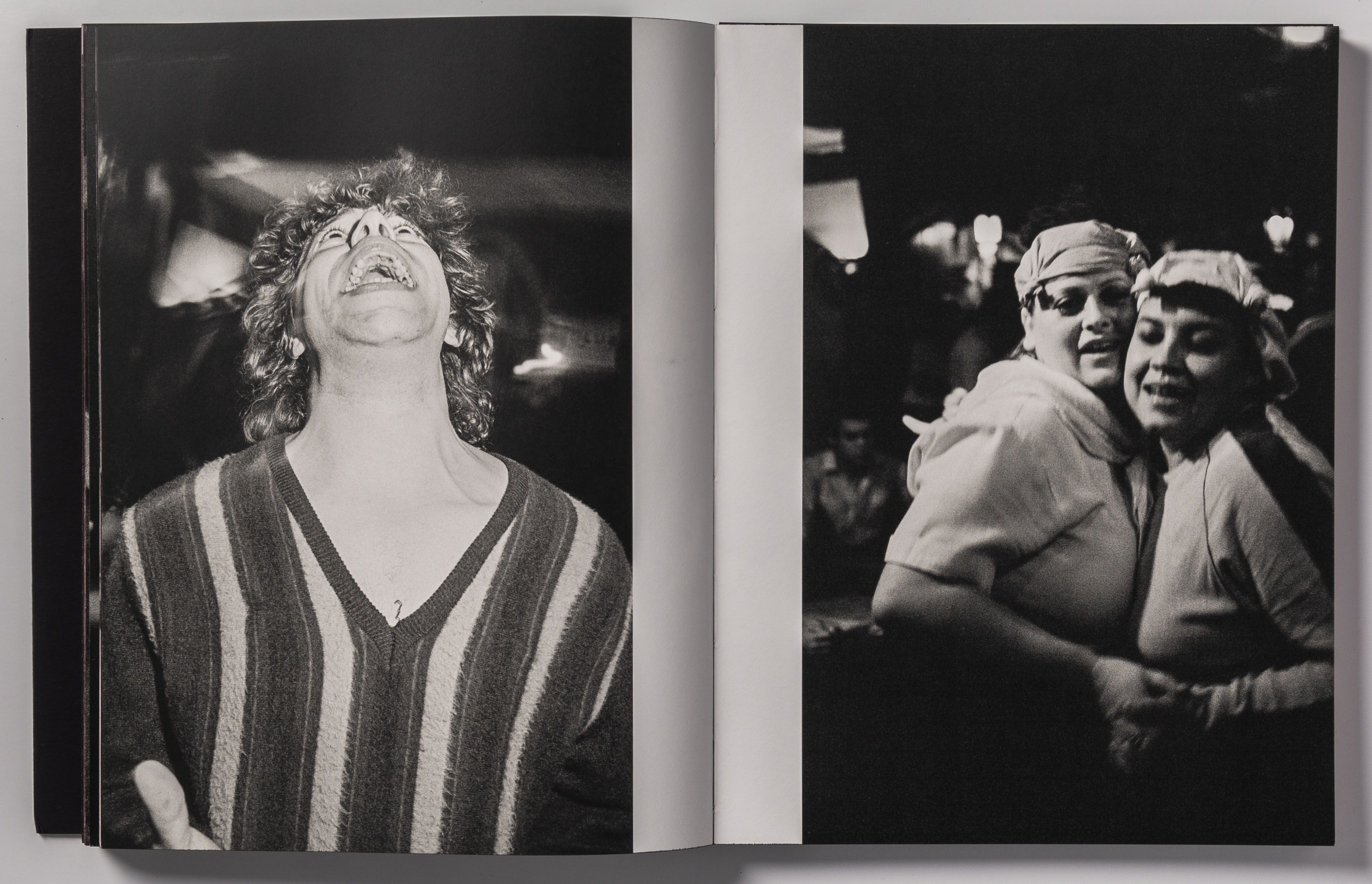

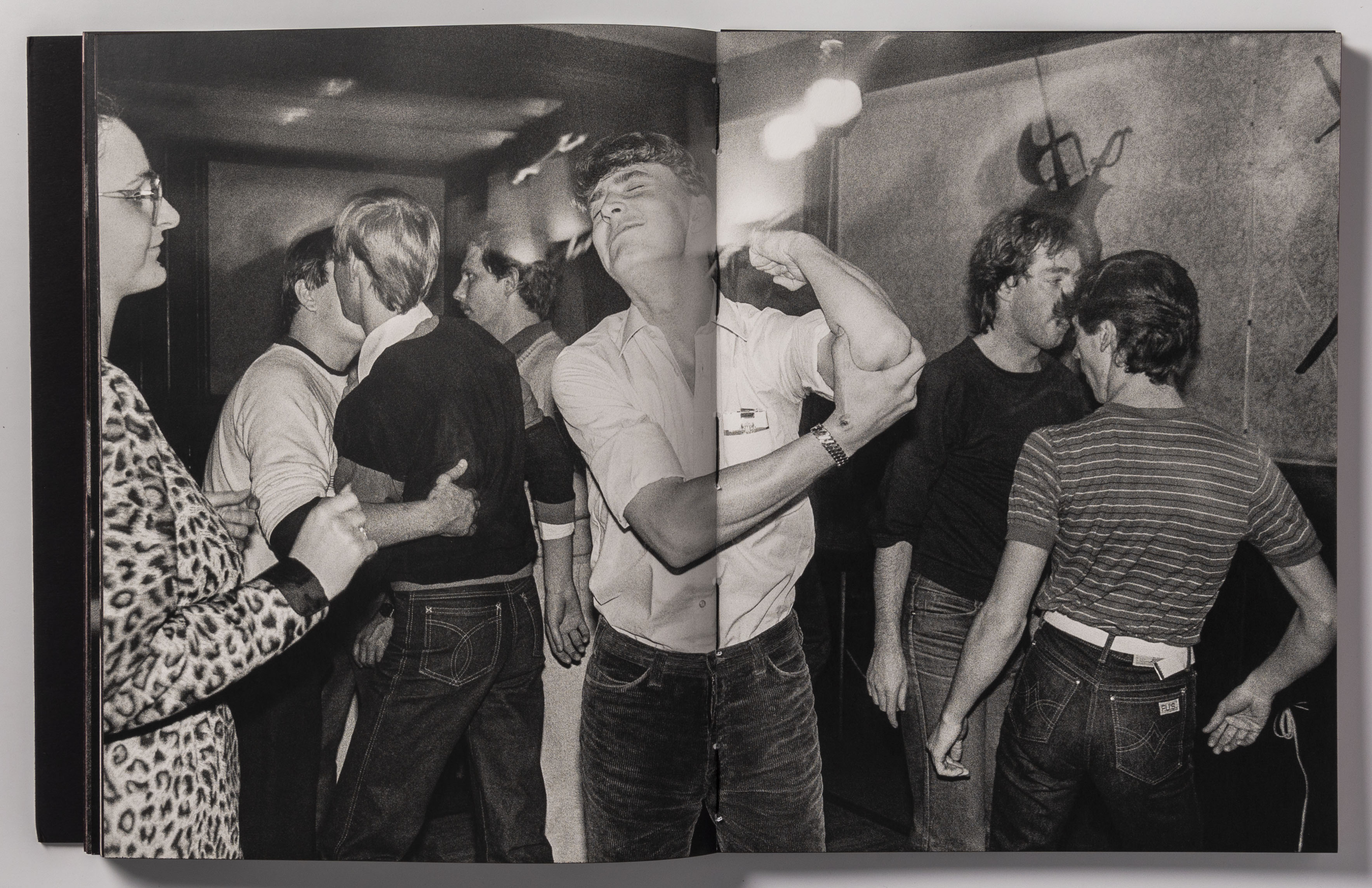

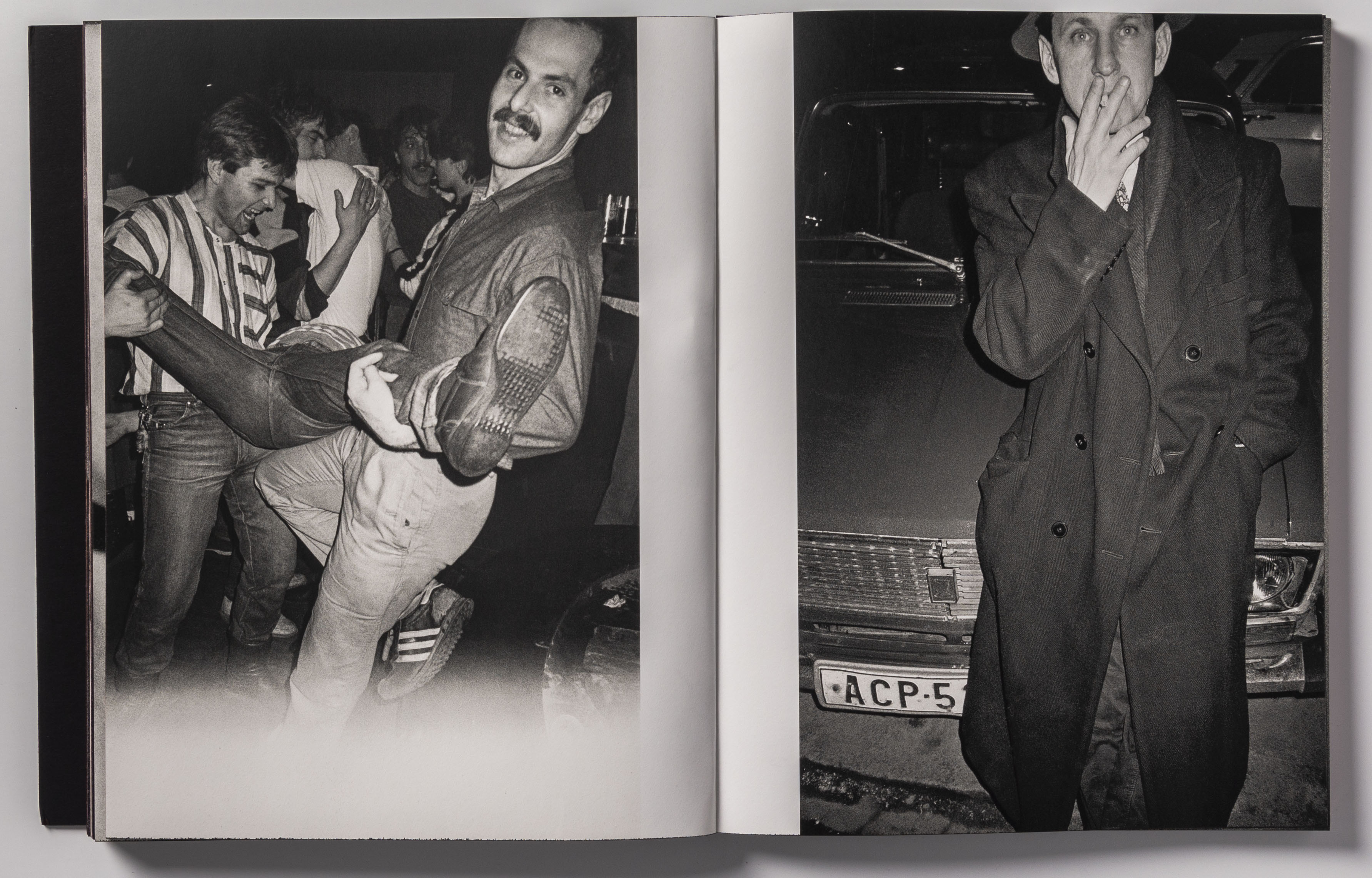

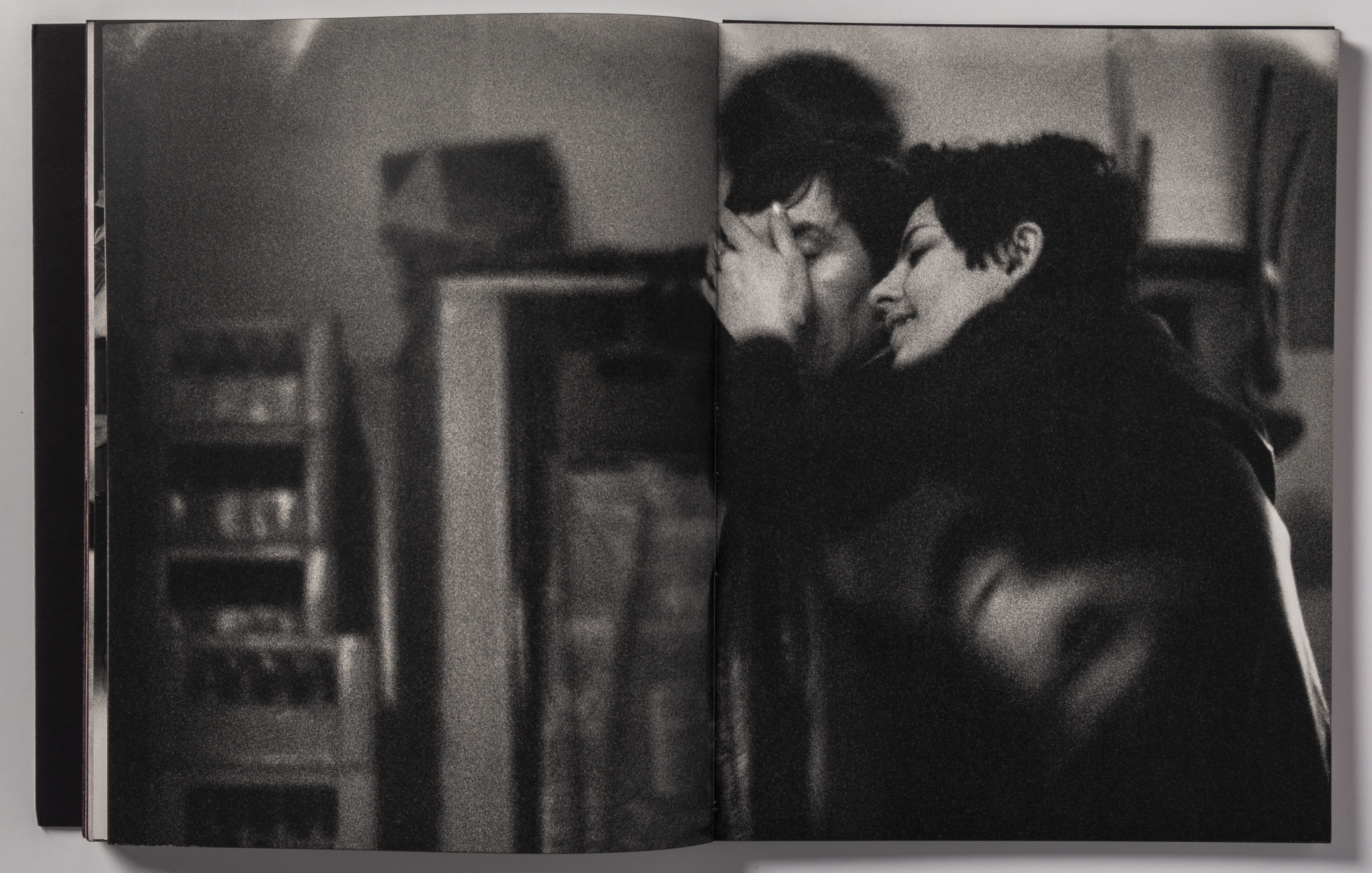

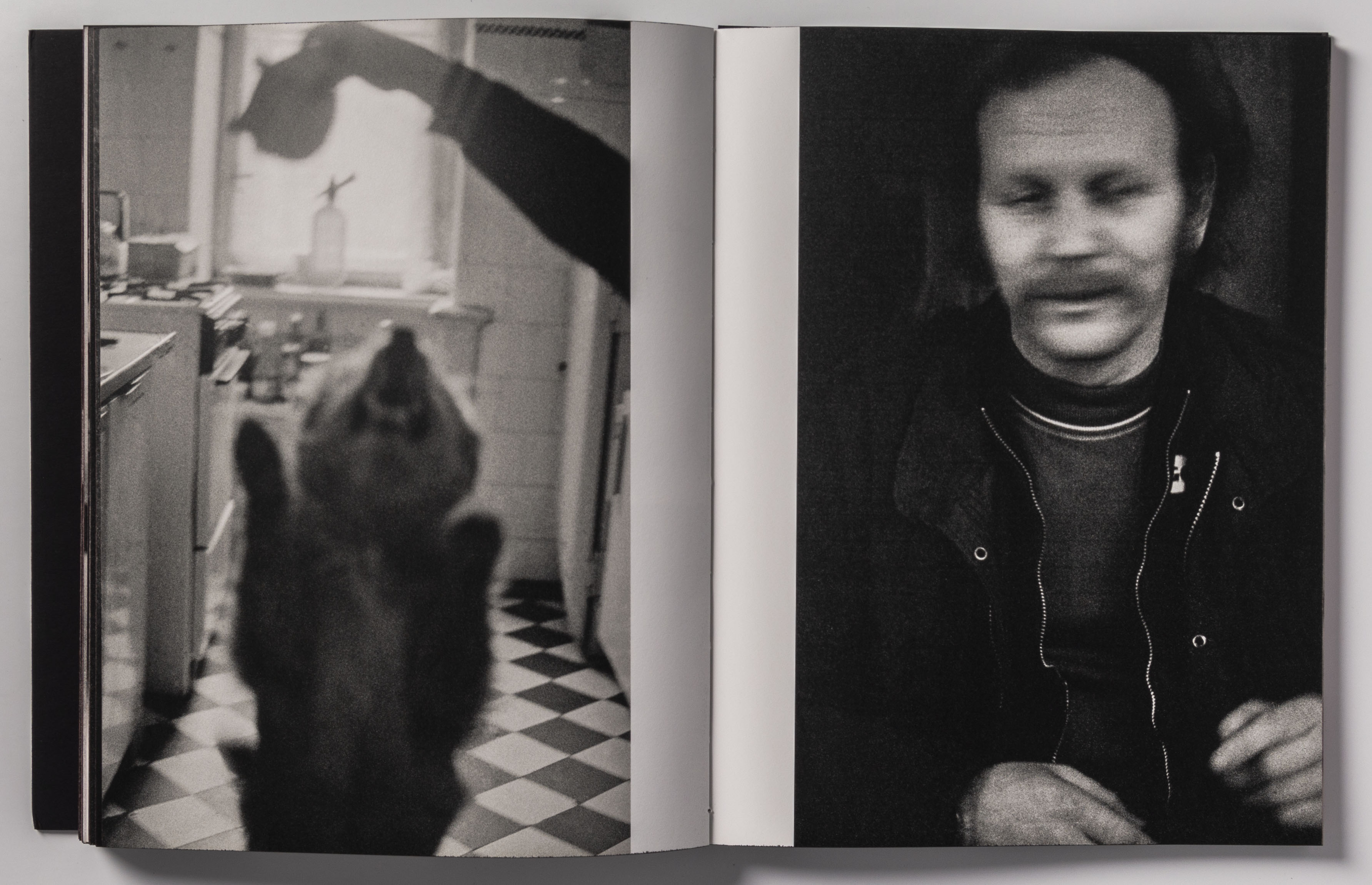

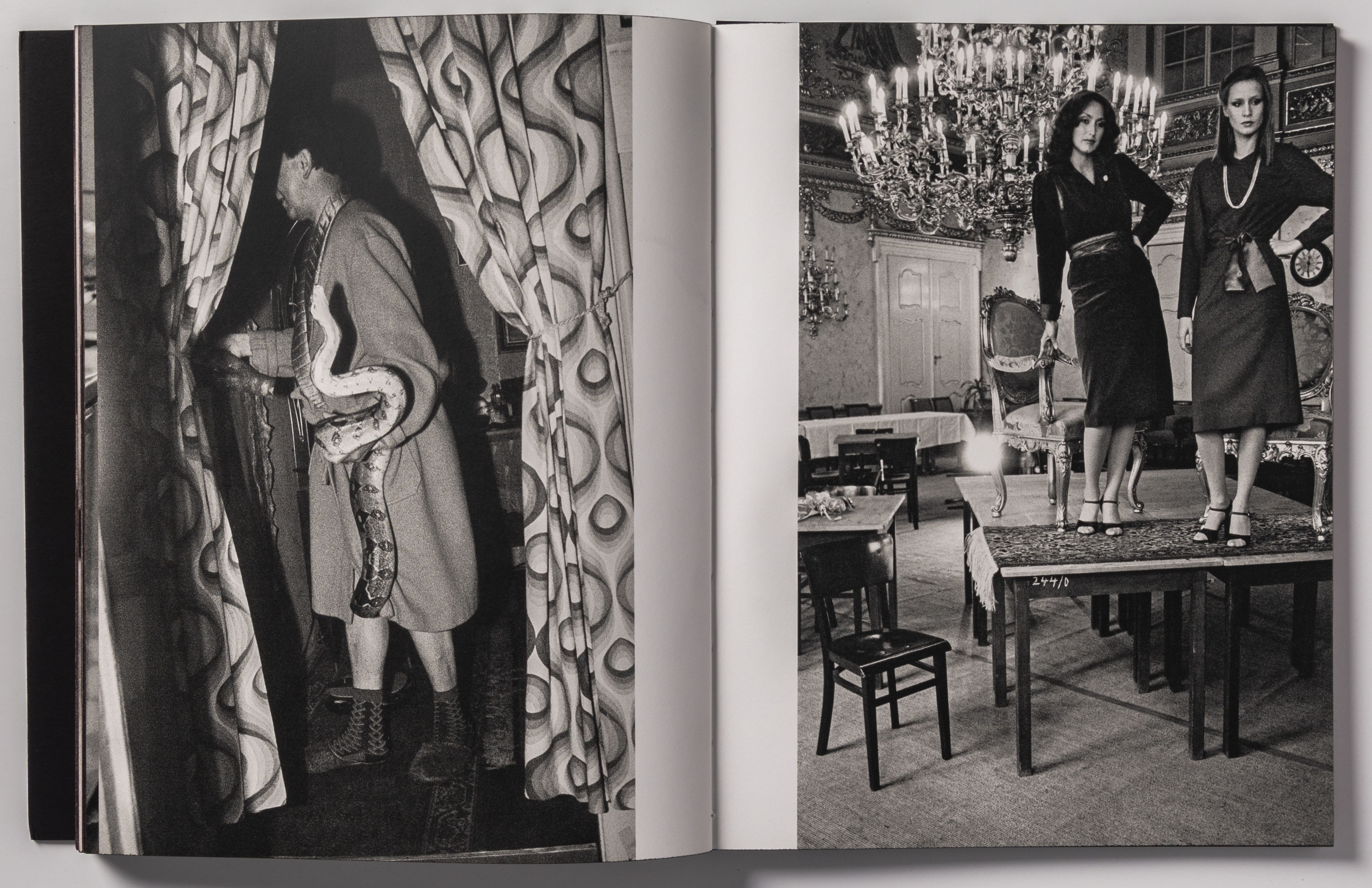

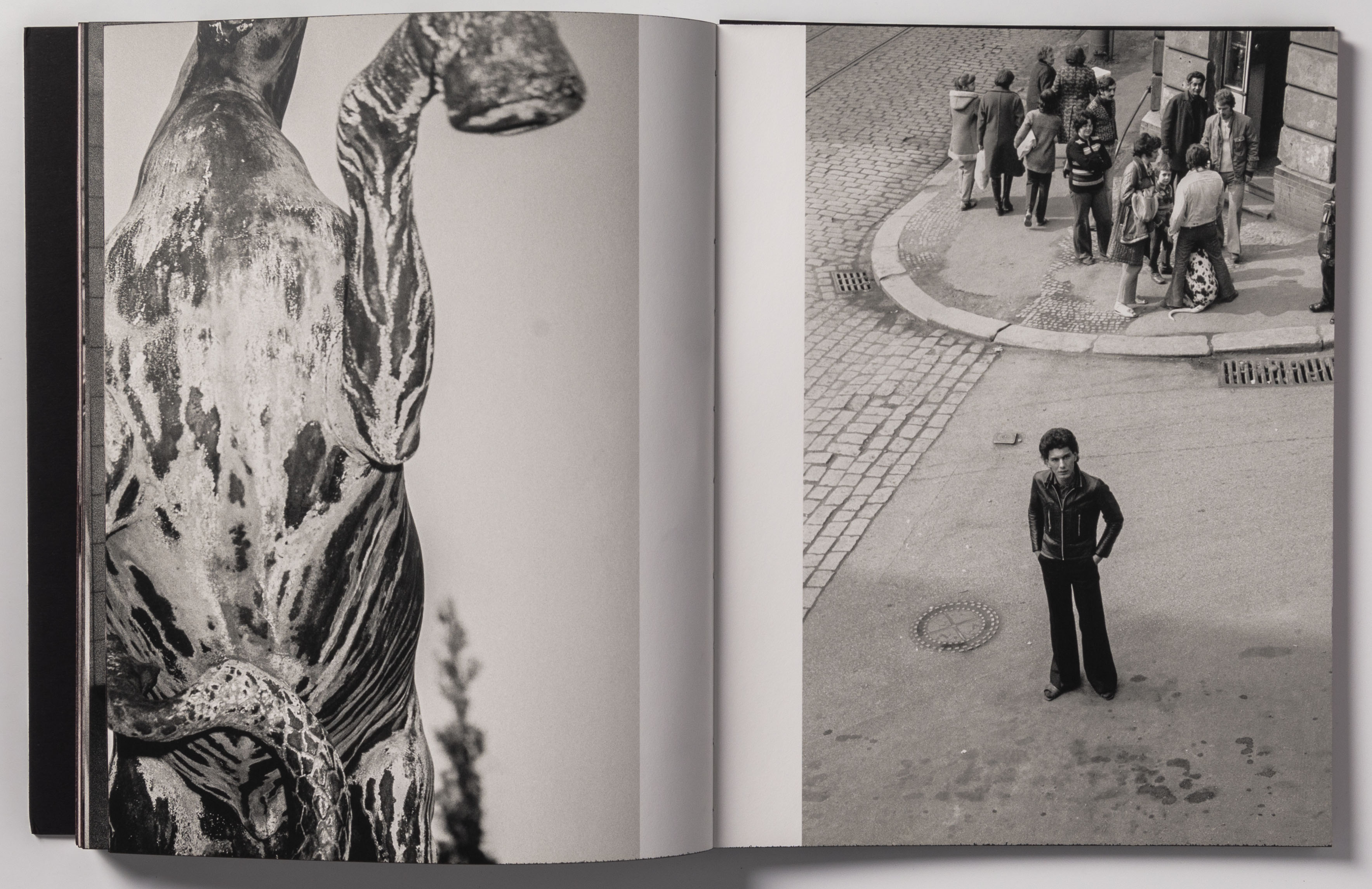

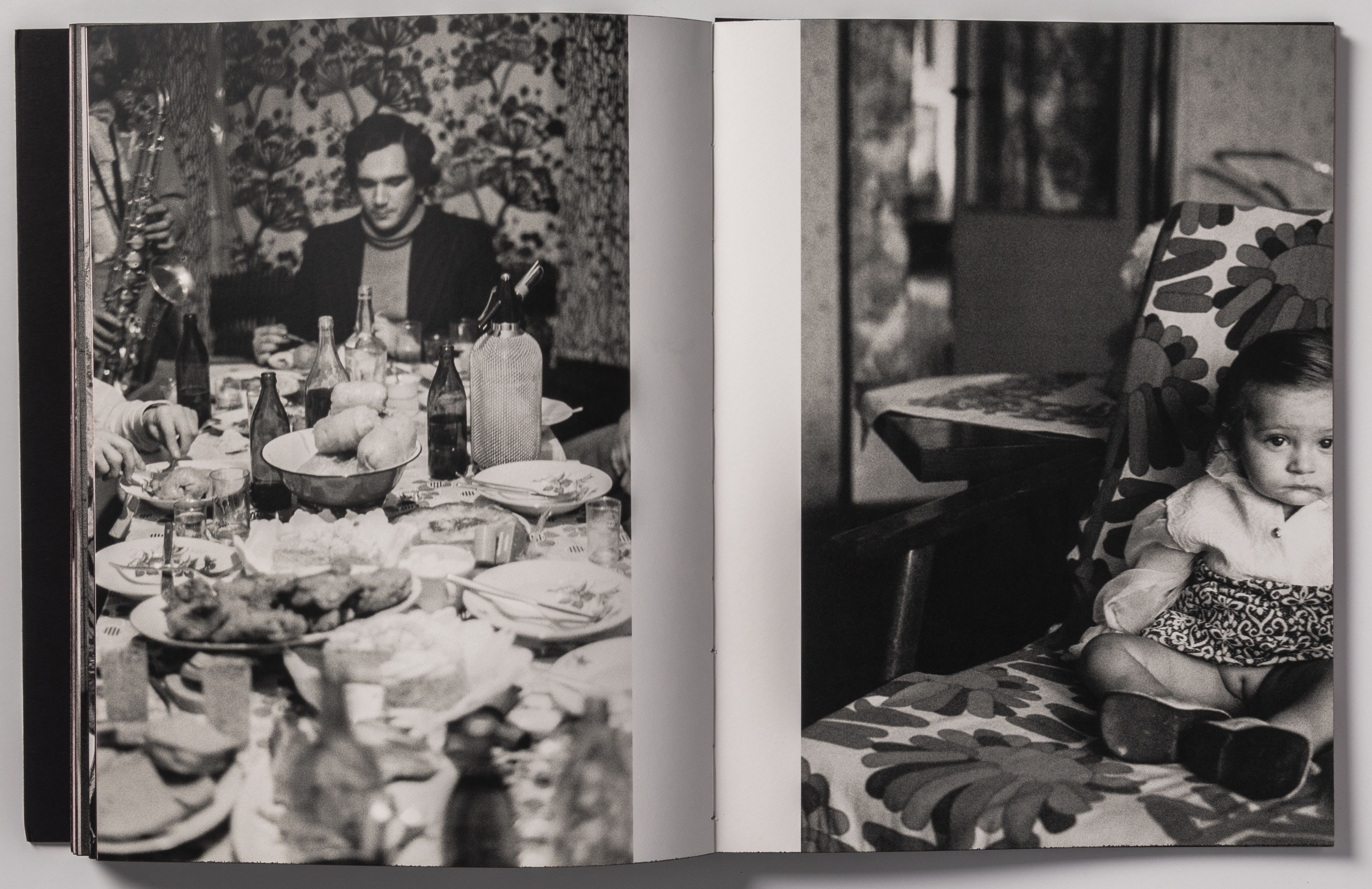

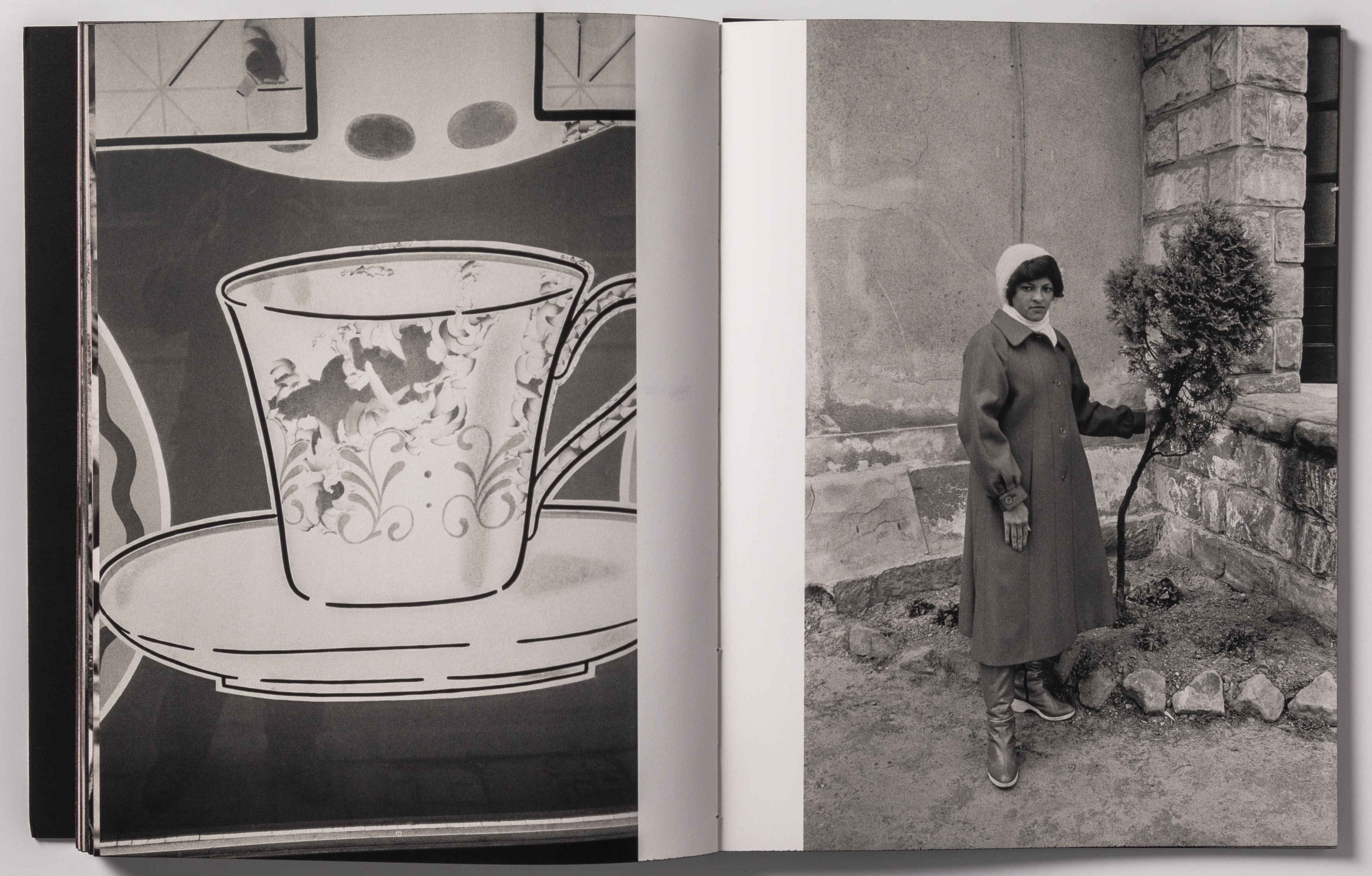

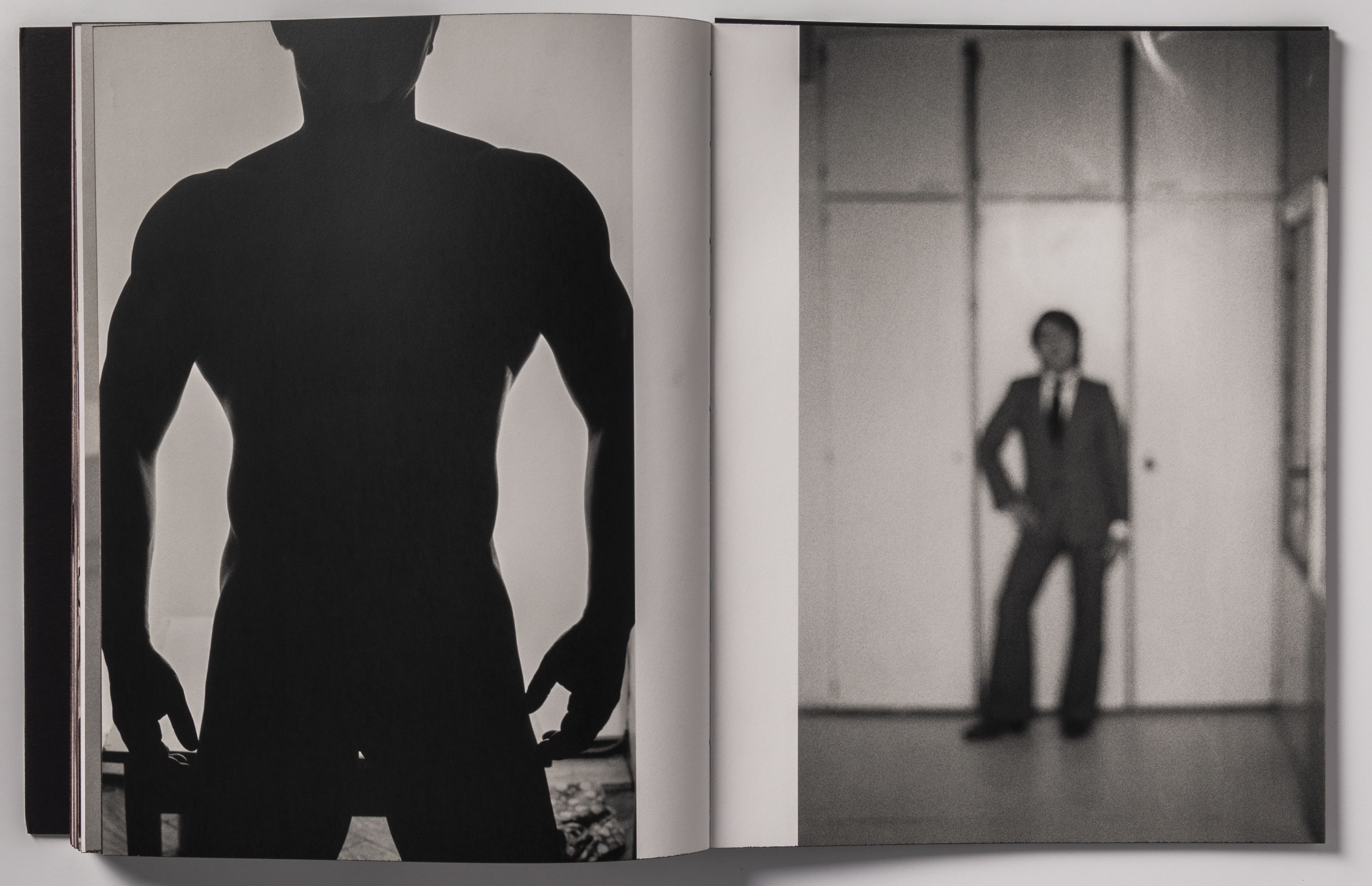

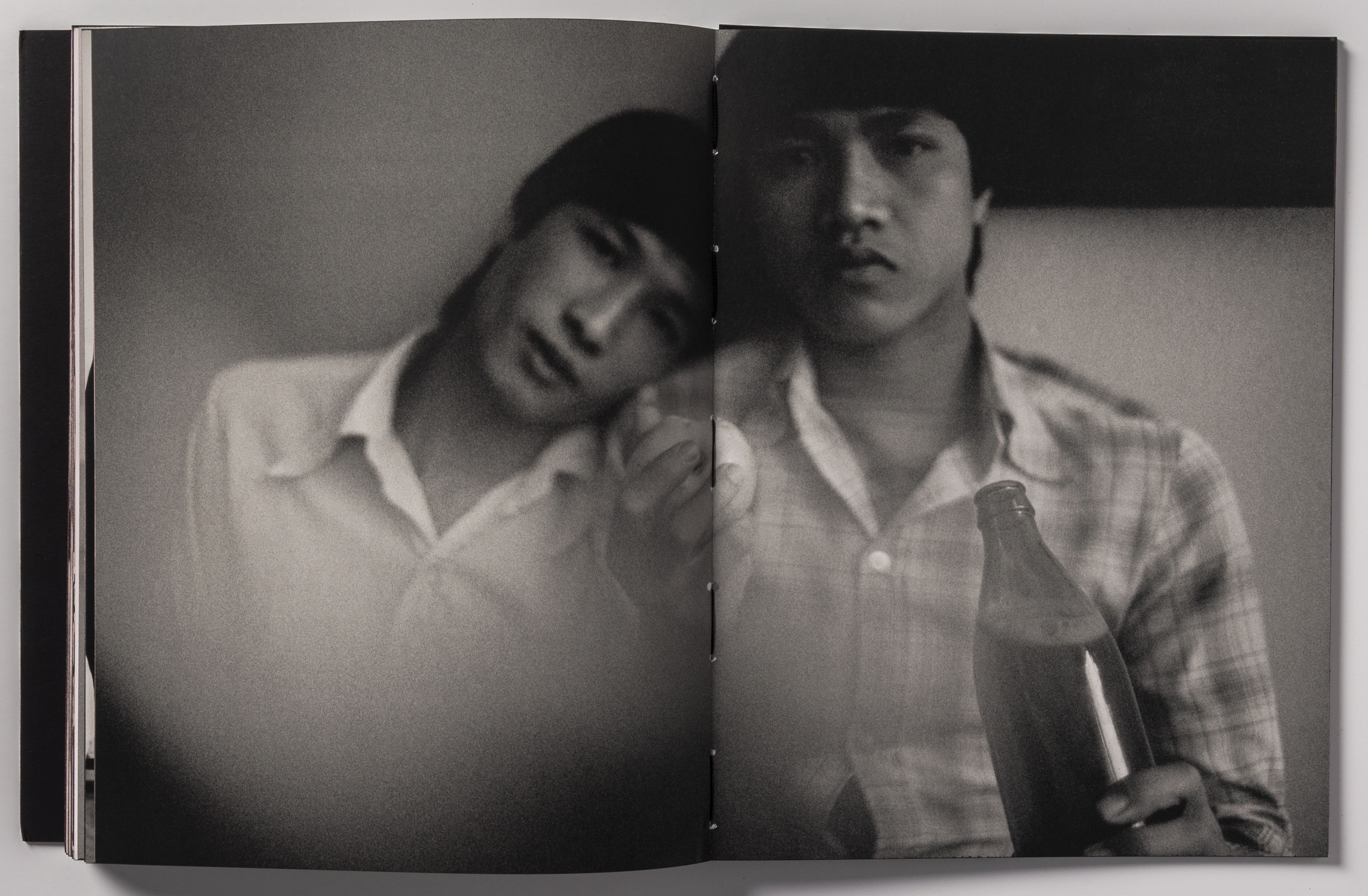

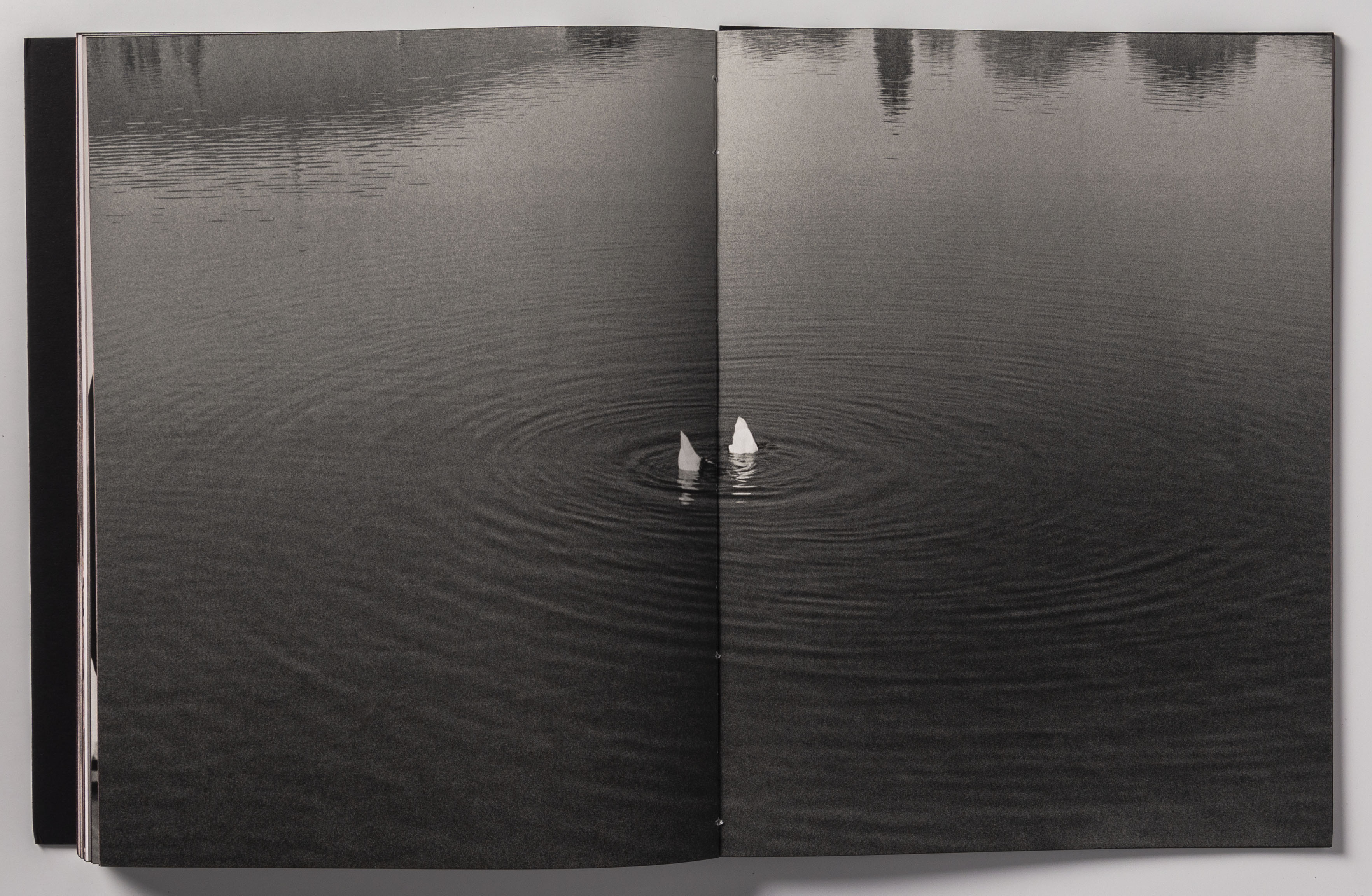

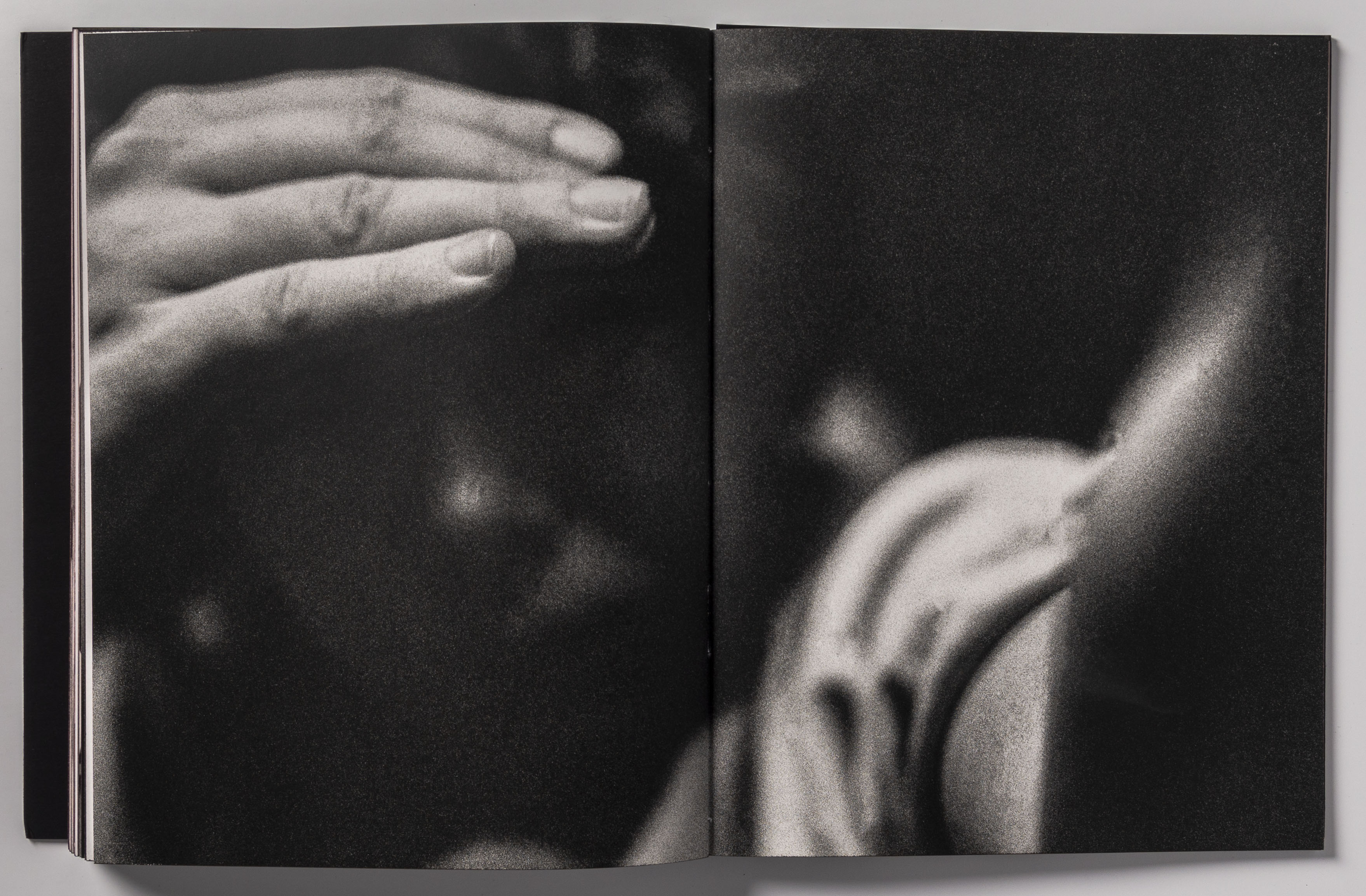

Recently Received: EVOKATIV by Libuše Jarcovjáková

I’ve been corresponding with a poet, Chris, who has been in prison since 2004. After purchasing EVOKATIVE, a book of photographs made by a young woman living in Communist Prague, I passed along to Chris this quote by the photographer, Libuše Jarcovjáková:

Faraway places, trips, adventures…that was what really appealed to me. But the Czechoslovakia of my childhood was a country bordered by barbed wire and you weren’t allowed to travel. It was a time of oppression, during which for more than 40 years we were the political vessels of a large Eastern empire. Everything was ideology, you were surrounded by political propaganda from morning to evening…Luckily, I didn’t really take in my surroundings. There was a world of books and pictures and I spent hours imbibing them.

Chris’s response is a better book review than I can write, even if he never got to see the pictures:

There is this fascinating duality in the concept of escapism in photography. The ability to capture the spirit of a place so full it serves as a portal. It’s so easy to romanticize it, especially when you’re living a life filled with longing. In the quote you sent, it appears the woman used the material to endure the limitations, to remind her of a broader perspective. But she says, “Luckily, I didn’t take in the surroundings” which I find somewhat impossible. There’s a quote by Marilynne Robinson that says “When do our senses know anything so utterly as when we lack it?” Her Czechoslovakian childhood is defined by these “faraway places” that come alive in her longing. It is where the value of these photographs come from, right?

See selections from EVOKATIV by Libuše Jarcovjáková HERE

The Lunch Table:

Ethan: I saw Little Women and it started a conversation about non-linear storytelling that was quite enjoyable—probably more than the film itself, but it is worth seeing. 7/10

Molly: Sam Youkilis (@samyoukilis), whose work I know from instagram, gracefully captures his worlds visited through short videos often showing the subjects like a photos in motion. 7.7/10

Ky: This week I watched Titicut Follies, a film by Frederick Wiseman where he exposes conditions at a Massachusetts hospital for the criminally insane. It was very eye opening to see actual footage of what it was like inside of these institutions during the 1960s. 7/10

Alec: I watched Aidy Bryant’s sitcom Shrill on a plane. I laughed out loud, but it might have been the elevation—you can’t trust my reviews of in-flight entertainment. 7/10