I’m currently on a road-trip with my 17-year-old daughter Carmen. The other day in Las Vegas she picked out a person for me to photograph. Her name was Clarina and she was a 25-year-old woman from West Africa. After I was finished taking the picture, Carmen interviewed her. She asked Clarina about the hardest thing she’d overcome in her life. After describing how she and her family fled the civil war in Liberia when she was 11, Clarina said something fascinating:

The civil war helped me learn how to feel for people. It really helped my five senses. I heard the cries from people. I saw their wounds. So in life now, when I talk to people, I’m able to feel them.

They say that adversity makes you stronger, but I like the idea that it heightens your senses.

In this newsletter:

- Picture & Poem: “A Loud Song, Mother” by Isabella Gardner

- Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: The Smoking Car

- Ex-Libris: A Loud Song by Danny Seymour

- Recently Received: Good days Quiet by Robert Frank

- The Lunch Table

Picture & Poem:

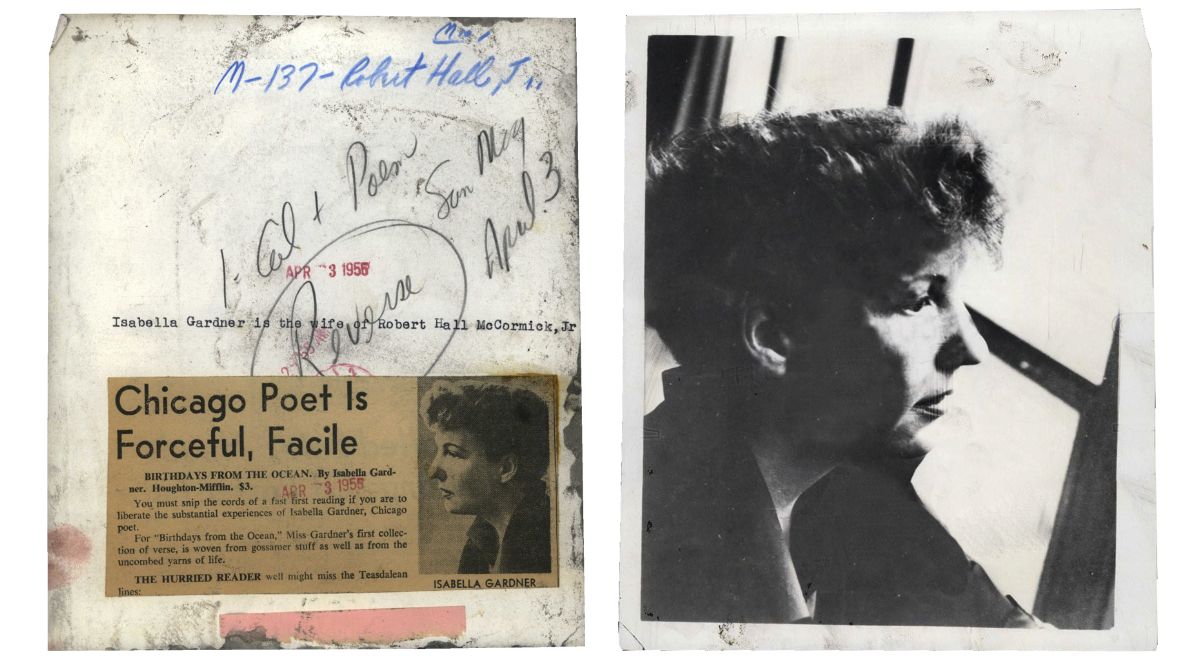

Isabella Gardner (1915–1981) faced a life of adversity. Her wealthy family (she’s the goddaughter of Isabella Stewart Gardner), covered up her teenage drunken driving accident that killed another passenger. At nineteen, she had an affair with a future president of Ireland, then married and divorced three American husbands. Her final lover was her doorman at the Chelsea hotel. “At almost sixty, she was an alcoholic, living with an illiterate hustler, spending her days watching television’’ her biographer wrote.

The story of Gardener’s children is equally tragic. After years of addiction and violent outbursts, her daughter Rose lived the rest of her life in an insane asylum. Her son, the photographer Danny Seymour, was likely murdered at sea while smuggling drugs from the Caribbean (his body was never found.)

Like her third husband Allen Tate and cousin Robert Lowell, Gardner was a poet. But she’s remembered mostly as a footnote in the lives of the men that surrounded her. The caption of the press photo above simply identifies her as the wife of her first husband Robert. But as the clipping itself attests, Gardner achieved some acclaim during her lifetime. I was excited to find copy of her selected poems, That Was Then. My favorite poem is the one about her son Danny entitled “A Loud Song, Mother.” It begins this way:

My son is five years old and tonight he sang this song to me. He said, it’s a loud song, Mother, block up your ears a little, he said wait I must get my voice ready first. Then tunelessly but with a bursting beat he chanted from his room enormously, strangers in my name

strangers all around me

strangers running toward me

strangers all over the world

strangers running on stars

I also appreciated Gardener’s melancholy afterword:

If there is a theme with which I am particularly concerned, it is the contemporary failure of love. I don’t mean romantic love or sexual passion, but the love which is the specific and particular recognition of one human being by another—the response by eye and voice and touch of two solitudes. The democracy of universal vulnerability.

Cosmic Fishing with Rebecca Bengal: The Smoking Car

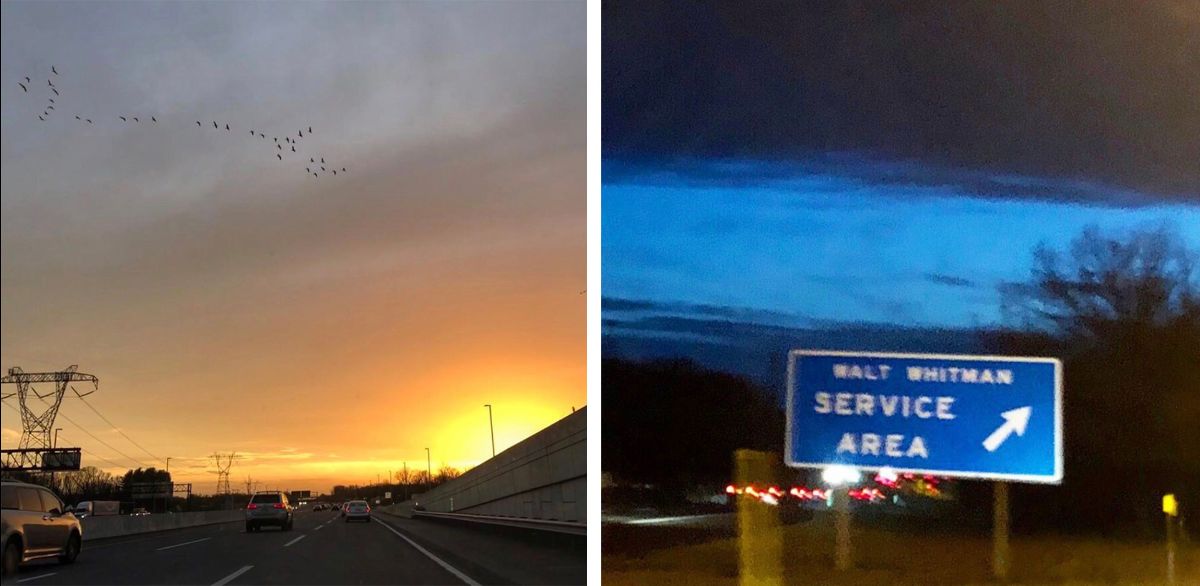

In New Jersey the sunset was atomic, condensed in a holographic shimmer on the far edge of the turnpike. Flocks of birds flew in Ys and Vs toward it, landing somewhere in the meadowlands of the pharmaceutical factories. They went west and I went south and the radio signal was turning to dust and the billboards were panicking. Posh DJs for Your Dream Wedding, read one, letters a bride and groom dancing in dry ice, the sign mounted on a tall, browning hill. A half mile down the road, Personal Massages, Couples Welcome, featuring what could have been the same bride and groom, perched uncertainly on the edge of a jacuzzi littered with red roses; probably moments later preparing for a costume change for their next photo shoot, the divorce lawyer billboard. I like to think in many parts of the country I am a pretty good radio DJ, not a posh wedding DJ by any means, but pretty skilled at navigating the airwaves finding the rare station at the right time. Part of driving is staying attuned to chance, but it doesn’t work everywhere. Out here, I expected, I’d be as unlucky as anyone else.

It was a Saturday in January and I had planned to leave New York hours earlier but it was sunny out and freakishly warm, and as wrong as that felt, I didn’t want to waste it in a car. I had nine hours to go and I didn’t mind night driving and so I decided to take my time. I went for a run and passed six other runners in shorts. I piled suitcases by the door like sandbags, remembering things all the things I imagined I might need for three months of writing and teaching and living at the ocean: crates of books, old cameras, guitar picks. I remembered I’d forgotten to try to fix my broken iPod so I spent about five minutes downloading a bunch of audiobooks, choosing them not always by the book but by definitely by the person reading them aloud. One of the ones I chose, based on both book and reader, was Spalding Gray’s monologue Monster in a Box. I was equally pleased to find another book of Spalding’s, Life Interrupted, this one read by Sam Shepard before he died. Both of them seemed like perfect company for the empty stretches ahead.

I’d picked up the car from the airport the night before and drove back to Brooklyn with all the windows down, failing to notice that it reeked of smoke. A hole the size of a cigarette was burned into the middle backseat. I decided I didn’t really want to picture the strangers’ wild night that ended in a Nissan Altima in an Alamo rent-a-car at JFK.

When Spalding Gray performed onstage, it was just him, a table, a microphone, a glass of water, the manuscript, a pared-down setup that felt like a mirror of a car dashboard on a darkening highway. Monster in a Box is his monologue about the writing of his 1,900 page novel, Impossible Vacation, which would later become a 228-page memoir. The monster is the novel. Or it is the suicide of his mother, which is also a subject of the book. Or it is both. I had not thought a lot about Spalding Gray in a while, perhaps not all that much since I wrote about his performance in David Byrne’s True Stories. I had always regretted that I never got to see Spalding Gray perform The Killing Fields or one of his other monologues live — but I didn’t live then in the kind of place where you might get to see Spalding Gray.

On the road music tends to lasso itself to the places along the way, attaching unearned significance to them. In that way I have tucked away songs on waysides all over the country. Now, in Jersey, Gray’s Monster in a Box attached itself to the Walt Whitman Service Area, where I am always compelled to stop, for the sheer evocation of the name. The road is always a story, a connector of places, and that night I especially wanted it to be. Driving I was keenly aware that I was not just in between states but, in my life, in between stages, in between projects, and therefore chasing connections and particularly susceptible to metaphorically loaded signs. I was also compelled to do something that I have had to do since I was nineteen and barely survived a car wreck in which I was badly smashed up, shattering both legs, requiring four operations since. To this day if my mother knows I’m flying or driving I send an intermittent update or I know she will sit around torturing herself imagining the same thing is happening to me all over again, even though nineteen was a long time ago now. So I texted from the Walt Whitman that I was alive and I got back in the car and Spalding Gray was writing in a little house in the same woods in the same artist residency in New Hampshire where I had once lived and written too, and this, too, felt like another small, and unearned connection.

Down the road, Monster in a Box attached itself to another nameless stop where shockingly to me people were hanging out as if they had not randomly walked into a corporate coffeehouse on a turnpike exit, but had intentionally chosen this as the destination for their Saturday night. A whole family had taken over a corner booth, parents and teenagers and little kids, and the dad was sprawled out, eyes closed, head thrown back, scone crumbles on the table, as Patsy Cline sang “I Fall to Pieces” and when I drove out of the parking lot, he had barely moved, if at all. By the time Monster came to a close, Gray had been through an earthquake in Los Angeles and a film festival in Moscow and a Reagan-era tour of Nicaragua and a failed attempt to answer phone calls at a suicide hotline over Christmas and a Broadway production as the stage manager of Our Town, and I had only gotten as far as Baltimore which is where I began Life Interrupted.

Talk about chance. I haven’t yet found any other books that Sam Shepard reads aloud (he didn’t, as far as I know, record any of his own) and he doesn’t attempt to try to sound like Spalding Gray. Instead, Shepard’s Kentucky printed itself onto Gray’s New England on a highway that pointed south to Virginia, once a place of Shepard’s too. As the title suggests, Life Interrupted is brief, shockingly so. Like Monster in a Box, it is on one level a story of an attempt to write a story. On a trip to Ireland with his family as a sixtieth birthday gift, Gray tells another friend—Barbara Leary, ex-wife of Timothy Leary—that he worries he will never write any more monologues. “My life is without crisis and usually they’re based on crisis, and I don’t have anything planned at all,” he tells her. “Things are going smoothly.”

But Leary insists she’s had a dream of Gray writing a new monologue, and besides, the signs are everywhere. Gray and his family are staying in a town named Mort, in a manor that resembles the house in The Shining, the same house, in fact, where their friend John Scanlon has recently died, and all the guests have agreed to go to dinner at Scanlon’s favorite restaurant where the talk centers on another friend’s car accident in a foreign country. Earlier that day obituaries were broadcast on the radio, Gray watched Irish gravediggers pause their work to take a smoke break, and, later on a rainy walk, the animals in the fields all seemed to bay and moo as if warning him; he alerted a farmer about the sick calf who had locked eyes with him, as if to communicate its enormous distress and pain. “I didn’t realize it would be the last long walk I would ever take,” Gray says in Sam Shepard’s voice. Shepard does a subtle Irish accent for the farmer who promises to call the vet, and for the the Irish nurses and doctors in the hospital where Gray is taken after he and his wife and friends are in a serious wreck on their way home from dinner — their car struck by the van of a veterinarian, who has probably just attended to the sick cow Gray alerted the farmer about.

I had downloaded the book without paying much attention to the title and it was only at this moment that I realized that this was the story of the car accident that would send Spalding Gray into a fatal depression. Almost two years before I moved to New York, Gray disappeared, last seen on the Staten Island Ferry in winter, his body eventually discovered two months later in the East River. I suppose I should have been more alarmed by the coincidence of this — of being on a long solo dark drive thinking about chance, passing wrecks on the highway, pulling over a couple times to text reassurances of my own intactness as I listened to a story of accidents and coincidence. What if I had walked back into the restaurant, Gray asks himself, what if I had buckled my seatbelt. Of the passengers, he is the only one with serious, debilitating wounds—a shattered hip, a head injury that will require surgery and a titanium plate, from which he will never truly recover, as friends and family describe in the tributes that bookend his starkly abbreviated monologue. Three years after the accident, after numerous tries to cure his depression, and after numerous suicide attempts, Gray took his children to see Tim Burton’s The Big Fish, which ends with the line A man tells a story over and over so many times he becomes the story. In that way, he is immortal. The next night he was gone.

I pulled over at a hotel in Virginia where I was checked in by a woman named Unique who was training a man named Christian and moments after I wheeled my things into an elevator, a rainstorm pelted the hotel room windows and the electricity in the room flicked on and off as the clock radio by the bed recaptured and flashed the date and the time, 11:11 pm, January 11, 2020. I was struck by a sudden curious thought. I opened my laptop and I typed Spalding Gray disappearance Staten Island Ferry and sure enough, I received: January 11, 2004, exactly sixteen years ago. So long ago that the world was less collapsed than it is now, that my relationship to news and the Internet and New York was far looser than it is now, and I was never conscious of the actual date he’d gone missing. Realizing this might have felt macabre and foreboding, but it didn’t. All of it — the presence of Sam Shepard, a writer I loved who was gone reading the writing of Spalding Gray, a writer I loved who was gone, on the subject of the significance of signs and augurs — should have felt macabre and foreboding, but it didn’t. Maybe it’s corny to say this, but it felt like a kind of honoring of the very nature of omens and chance, a confirmation that there were signposts along the way, of a subterfuge of connections, of the rightness of the road and maybe too of stories.

I let The Killing Fields play until my laptop died. I had left all my chargers in the smoky Altima and I didn’t trust the clock radio, flickering green in the storm as the rain fogged the windows onto the parking lot. I dialed the front desk and asked Unique for a wake-up call. It was late and tomorrow I still had a long way to go.

Dear Lester:

Dear Lester: How can I stop daydreaming about the last goal I scored during the last match I played in the Italian amateur soccer league 16 years ago? – Federico

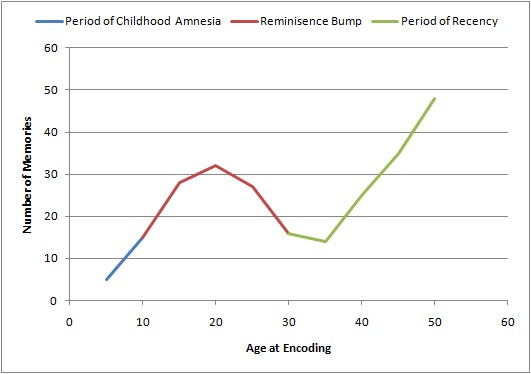

Dear Federico: The term “reminiscence bump” refers to our tendency to have a better memory of positive events that occurred during our adolescence or early adulthood. This explains why I still listen to REM and you still think about that goal.

To create a new, equally sticky reminiscence you’ll need to have a “flashbulb memory.” Wikipedia describes these memories as deriving from events which have “the surprise, indiscriminate illumination, detail, and brevity of a photograph.” The prototypical example is the assassination of JFK. But instead of waiting to be surprised by a catastrophe, I recommend going out and taking your own flashbulb photos of something unexpected.

*

Dear Lester: How would you go about photographing a situation wherein: Your parents divorced when you were three, and then remarried other people, and you grew up with those people. Then both sets of parents got divorced. All four parents have life threatening diseases. They all call on you daily for help with snow shoveling, household chores, moving heavy things around, and help feeling like they still belong to a family, even though they’re all isolated and suffering. – Kaylen

Dear Kaylen: While I might not share any of the specifics of your predicament, your frank question evokes the “democracy of universal vulnerability” described by Isabella Gardener above. I suggest you lay bare this vulnerability. How to go about this? The answer, perhaps, is with the specificity in which you describe your plight.

In an interview with BookForum, Karl Ove Knausgård discusses how he spent four years trying to convey his struggle through fiction. But the story he wanted to tell, “the story of my father, of his fall from being a respected member of society to a drunk dying in a chair in his mother’s house without anything left,” was one that resisted fictional details and story arcs. He ended up telling it as directly as he could:

I want to evoke all the things that are a part of our lives, but not of our stories—the washing up, the changing of diapers, the in-between-things—and make them glow. Though a five-page description of what’s in a closet is not exactly page-turner stuff, I thought of this project as a kind of experiment in realistic prose… no one wants to be boring or banal, but that was what I set out to do.

Knausgård’s book wasn’t boring, of course. My Struggle went on to become an international phenomenon. His artful but storyless description made countless readers feel less alone. Perhaps your answer is in your question: Snow shoveling, household chores, moving heavy things around. Depict your struggle – and make it glow.

Do you need advice?

Creative or otherwise.

Email Lester: DearLester@LittleBrownMushroom.com

Ex-Libris: A Loud Song by Danny Seymour (1971)

While Danny Seymour’s book takes its name after a poem by his mother, it is dedicated to father, a Russian Jewish immigrant photographer named Maurice Seymour:

I was proud of my father, I believed then, as I do now, that he was the best photographer in the world. When I turned to photography, it was as a drowning man reaches for a life raft. My life and mind was in chaos, undirected and unhappy. I had been deserted by a woman I loved, and I was none too stable to start with.

A Loud Song is both family album and confessional diary. It is heavily influenced by his mentor Robert Frank but gives even more emphasis to text. “It is an attempt to survive – to preserve my identity,” he writes, “Is it exhibitionistic? How else to say something real?”

Along with loving pictures of his family, Seymour reproduces a letter from his step-father Allen Tate suggestion he should be cut off from the family’s fortune and a photograph of his sister Rose working as a stripper in San Francisco. The most reproduced photographs from the book are pictures from his loft showing Robert Frank, Jessica Lange and John Lennon.

The penultimate text is scrawled by Robert Frank himself in 1971:

I liked Danny right away. Danny is 26 and I am 47. We live in the same building – look out on the same street, the Bowery in New York City. Danny has a lot of dope and a lot of despair. He also has friends who share with it with him. But Danny is an artist and if he’ll survive – we all will be happy and richer to see what he has done.

Two years later Danny was gone. The boat he’d sailed to the Caribbean to smuggle drugs was recovered and he was presumed dead, likely from murder. (For more on this story, I recommend the book Greed, Rage and Love Gone Wrong: Murder in Minnesota.)

The final text in the book is scrawled underneath a beautiful photograph Danny took at night when he was ten years old. “I developed the negative, printed it, mounted it, and titled it – all in deadly seriousness – a timeless work of art.”

Recently Received: Good days Quiet by Robert Frank (2019)

Robert Frank’s last book is as informal as a notebook doodle. On one double-page spread showing his house in Mabou he scrawls “graues meer – altes Haus hörst Du die Musik” (grey sea—old house / can you hear the music).

The book closes with an image of binoculars beside a window and Frank’s last published words: “Watching the crows.”

The Lunch Table:

Ethan: My friend recently gave me Home Ground: A Guide to the American Landscape. It is a wonderfully specific glossary and etymology of words relating to the landscape that captures a sense of our evolving relationship with the land. 8/10

Ky: I saw Chelsea Jade open for Your Smith at the Fine Line this week. It was not the typical type of music I listen to, but her choreography and stage presence alone made the show worth it. 9/10

Molly: This week I took myself to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in downtown Santa Fe. I wanted to photograph the works I was told I couldn’t; most notably her watercolor work titled Blue Shapes. Still wishing I had.. 9/10