Carrie Thompson: When I was pregnant I had a studio visit with Lorna Simpson. She is a mother, so I asked her for advice. I wanted to know what I should do before I have my baby. What would be the challenges for me when I become a mother? She said that since I had been working on two projects dealing with family history, including a trip to Japan that directly preceded my son’s birth, I should write down the narratives of those photos. She said I had to do this before my child was born. She repeated the advice a few times. I didn’t listen. I didn’t write the stories. I should have. When my son was born everything changed. My extra time disappeared. Making work slowed way down. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the challenges of balancing motherhood with a career as an artist. I decided to get some other photographers/mothers engaged in a conversation on the subject.There are a few things that I want to address. I want us to talk about being women, mothers and artists and how we find balance. How do we continue to make work, raise children and continue/find success? Alec is obsessed with age on this blog (see here). I think something important was missing from that discussion. No one seemed to address the fact that many people over 35 have children, families and other responsibilities. Do you as mothers think that having children makes it harder to be successful?

Greta Pratt: To the first question I have to say that it completely depends on how you define success. If success is defined as a mad dash to the top of the ladder and whoever gets there first is successful then yes having children definitely interferes. But if success is defined as quality of life as in being loved and showing love and having deep, long term relationships that cause you to question the meaning of life and love and art and help you to look at the world through different eyes well then I would say that having children helps you to be successful.

Greta Pratt: To the first question I have to say that it completely depends on how you define success. If success is defined as a mad dash to the top of the ladder and whoever gets there first is successful then yes having children definitely interferes. But if success is defined as quality of life as in being loved and showing love and having deep, long term relationships that cause you to question the meaning of life and love and art and help you to look at the world through different eyes well then I would say that having children helps you to be successful.

Beth Dow: I can’t lay claim on the word “successful” but I can substitute “productive”. I envy people who can switch on their focused mind in an instant. Focus for me comes much more inconsistently, and if I’m really engrossed in something, the worst thing that can happen is real life getting in the way. If I suddenly need to get someone from school, for example, it’s like a million little bubbles popping. It’s difficult for me to regain that focus later. This is especially true when I’m writing. When the kids were little and I had a tight deadline, I warned the kids they could only interrupt me if they were bleeding especially badly. Black humor fuels our household. Now to address the “harder” part of “harder to be successful”. I often feel like I should apologize to my kids for having a career, and to my career for having a life.

Paula McCartney: I just read Beth’s comment after listening to my two and a half year old yell from his bedroom in both in joy and despair for two hours in an attempt to not got to sleep while I sat in the living room trying to prepare tomorrow’s photo history lecture. I can definitely relate to finding it difficult to focus. When Oliver is talking-whether in the same room or not-I find it extremely hard to concentrate on anything else. Having a child and an art career, and teaching is a lot to juggle. I always wonder and ask other women how they do it. The most helpful response was from a photographer that I greatly admire who said “sometimes you are a not-so-great artist, sometimes a not-so-great mother, and sometimes a not-so-great teacher.” Hearing that made me feel not so bad about being not so great all the time at everything I was trying to do. Since grad school I made the decision to define success as continuously moving forward in some way, even if very slowly. And while I continue to ask artists with children how they do it, always hoping for some bit of wisdom that will make doing it easier, I realize that I am doing it too. For me, finding some balance (though that word makes life seem a little more stress-free than it is) happened when my son started going to day care two days a week and I had those days as studio days. I could focus on my work those days, teach a few mornings and be genuinely present when I was with him. The thing that I have seemed to sacrifice in being an artist and a mother of a young child and teaching is having a social life. In the whirlwind of the first two years I didn’t pay that much attention but have recently made much more of an attempt to make dates with my friends (mostly other women artists, many with children). When I think of all the women I am friends with who are artists, the ones that would be considered as more successful are the ones with children. So, I guess that no, having a child doesn’t make you less successful, only more tired. And while for me, life is definitely more difficult with a child, it is also definitely more amazing.

Paula McCartney: I just read Beth’s comment after listening to my two and a half year old yell from his bedroom in both in joy and despair for two hours in an attempt to not got to sleep while I sat in the living room trying to prepare tomorrow’s photo history lecture. I can definitely relate to finding it difficult to focus. When Oliver is talking-whether in the same room or not-I find it extremely hard to concentrate on anything else. Having a child and an art career, and teaching is a lot to juggle. I always wonder and ask other women how they do it. The most helpful response was from a photographer that I greatly admire who said “sometimes you are a not-so-great artist, sometimes a not-so-great mother, and sometimes a not-so-great teacher.” Hearing that made me feel not so bad about being not so great all the time at everything I was trying to do. Since grad school I made the decision to define success as continuously moving forward in some way, even if very slowly. And while I continue to ask artists with children how they do it, always hoping for some bit of wisdom that will make doing it easier, I realize that I am doing it too. For me, finding some balance (though that word makes life seem a little more stress-free than it is) happened when my son started going to day care two days a week and I had those days as studio days. I could focus on my work those days, teach a few mornings and be genuinely present when I was with him. The thing that I have seemed to sacrifice in being an artist and a mother of a young child and teaching is having a social life. In the whirlwind of the first two years I didn’t pay that much attention but have recently made much more of an attempt to make dates with my friends (mostly other women artists, many with children). When I think of all the women I am friends with who are artists, the ones that would be considered as more successful are the ones with children. So, I guess that no, having a child doesn’t make you less successful, only more tired. And while for me, life is definitely more difficult with a child, it is also definitely more amazing.

Danielle Mericle: I (like everyone) am so busy most the time I forget how useful camaraderie can be. That said, I’ve been surprised at the positive impact motherhood has had on me, both in a general sense and artistically. I was one of those who had little or no interest in having kids, so when I found myself pregnant I was pretty terrified at what it might mean to me. Much to my relief, I’ve found that it has made me less anxious about “career,” more genuinely invested in the process of creating, and happier in general. I think this is for a few reasons- first, I simply don’t have the time to be anxious anymore- after the full-time job and Charley (and house, food, exercise, etc) I get on average half day per week to focus on my work, so when I’m in my studio, I’m working. And it feels so nice (and necessary) to have that space to work, however little the time. I also have experienced (a cliche, I know) a major shift in my priorities- I’m not sure that I can entirely articulate the change, but I know that my definition of success is different- and has much less to do with the notion you have in art school of art-stardom, but rather is a better match for what I really want to do in life (which, fundamentally speaking, is to have an interesting and fulfilling life). This is not to say that it’s been totally rosy and without issues. My darker moments have come over battles for time. My husband is a working artist too, and the struggles for an hour here or there have been throughout our tenure as parents (almost three years now). For whatever reason, I’ve had a tendency to relinquish my time more than I would like, which has been a really terrible habit that I’ve had to consciously break. If I had any advice to a new mother/artist, it would be to guard what little time you have- it may not feel like much to give up an afternoon, but from a sanity perspective it’s huge. Other things- I too have little or no social life, which is fine for now. I’ve worried that we’ve alienated a few people around here, but there’s not much to do about it (and fundamentally I don’t know that we really have). And I don’t read anymore- this drives me crazy- and I’m really looking forward to that coming back.

Amy Stein: Danielle’s comments really resonate for me. Many are spot on to my recent experiences as a mother. I too feel less anxious about career concerns than I did before Sam cam along. I used to be very consumed by my work and career and now I feel I’m much more relaxed about it and have more perspective on it’s trajectory as well as many other aspects of my life. The cliches we often hear are that motherhood is “transformative” and “puts things into perspective, are uttered so often because are true and still they don’t go far enough to describe the awesome, overwhelming changes that motherhood brings. In the past six months these changes have overwhelmed me and thrown everything I knew before out the window. I am still adjusting to the countless large and small impacts on my life. But as a 41 year old first time mom, I welcome those changes. I think I was getting used to the idea that the major positive changes of life were over for me. I switched careers at 32, built a new career in the arts that was satisfying and rewarding. Sure I still had a long way to go, but I was happy to plug away at it everyday. And grateful that I could spend my days making thinking and teaching photography. We tried for a long time to get pregnant. We went through a lot to have a child and just before I got the good news I had resigned myself to the fact that it just wasn’t going to happen for us. Then along came Sam. Of course there’s joy and the deep connection of having a child, which has made my life immeasurably fuller and more meaningful. As Danielle says there’s less time to worry about yourself, which for me is a good thing, because I was spending about 90% of my time before motherhood fretting over work, career and meaning in my life. And now there’s so much meaning that those demons are crowded out, swept away. I think we as artists and mothers struggle with the same issues most working moms struggle with: limited time, overwhelming demands on our time in and outside the home, wanting to do well with career and personal and home life and not being able to because often it’s just not possible to do it all well. And as Danielle mentions the constant negotiations with one’s partner about who will care for your child and when are wearing. Then there are the financial concerns: how to pay for childcare, etc. And finding that balance of how much childcare you need to do your work and for me fighting the guilt over watching someone else spend large amounts of time with my son as I answer emails and photoshop files at my desk ten feet away. But then feeling incredible relieved when the work gets done. But missing my son at the same time. It’s a cocktail of joy, resentment and guilt.

Amy Stein: Danielle’s comments really resonate for me. Many are spot on to my recent experiences as a mother. I too feel less anxious about career concerns than I did before Sam cam along. I used to be very consumed by my work and career and now I feel I’m much more relaxed about it and have more perspective on it’s trajectory as well as many other aspects of my life. The cliches we often hear are that motherhood is “transformative” and “puts things into perspective, are uttered so often because are true and still they don’t go far enough to describe the awesome, overwhelming changes that motherhood brings. In the past six months these changes have overwhelmed me and thrown everything I knew before out the window. I am still adjusting to the countless large and small impacts on my life. But as a 41 year old first time mom, I welcome those changes. I think I was getting used to the idea that the major positive changes of life were over for me. I switched careers at 32, built a new career in the arts that was satisfying and rewarding. Sure I still had a long way to go, but I was happy to plug away at it everyday. And grateful that I could spend my days making thinking and teaching photography. We tried for a long time to get pregnant. We went through a lot to have a child and just before I got the good news I had resigned myself to the fact that it just wasn’t going to happen for us. Then along came Sam. Of course there’s joy and the deep connection of having a child, which has made my life immeasurably fuller and more meaningful. As Danielle says there’s less time to worry about yourself, which for me is a good thing, because I was spending about 90% of my time before motherhood fretting over work, career and meaning in my life. And now there’s so much meaning that those demons are crowded out, swept away. I think we as artists and mothers struggle with the same issues most working moms struggle with: limited time, overwhelming demands on our time in and outside the home, wanting to do well with career and personal and home life and not being able to because often it’s just not possible to do it all well. And as Danielle mentions the constant negotiations with one’s partner about who will care for your child and when are wearing. Then there are the financial concerns: how to pay for childcare, etc. And finding that balance of how much childcare you need to do your work and for me fighting the guilt over watching someone else spend large amounts of time with my son as I answer emails and photoshop files at my desk ten feet away. But then feeling incredible relieved when the work gets done. But missing my son at the same time. It’s a cocktail of joy, resentment and guilt.

Linda Rossi: This is a wonderful opportunity to write about our adventures- as mothers and artists- I so appreciate these reflections. I have three sons who unfortunately due to crazy circumstances I had to raise from a young age on- by myself. My first son was born the day after my grad school exhibition. As I still had to finish the written part of my thesis- I was nursing and writing at the same time. I found it completely changed my interpretation of time and space- there was a blending and compression- I needed to accept quickly the chaos and the unexpected. As the years went on all 3 helped me make works of art- their skills and aesthetic knowledge grew and I was able to trust them (at a young age) for new insight into the work. It has continued to be a provocative and powerful exchange. During those years it was a matter of finding bits of time that I could create work,so a lot of the time I was dreaming about pieces -not actually making them- I would actually try to schedule time to make art in my head- for example while washing the dishes I would focus intensely on the work I would do in the future. At the same time one would find domestic and artistic tools side by side on the kitchen counter- the loaf of bread and peanut butter were spread out with saws, wood, etc. Probably not the most sanitary- but it was a way to not separate our lives. I look back now on years that were filled with pain, beauty, terror, humor,profound baby -teenage boy smells, and yelling and and fear and laughing and it still continues. The intensity of the home fueled the work I created. During a certain time period I created an elaborate installation about Russian poets whose voices were suppressed by Stalin. I became interested in the power of art during a time of danger- the strongest work was less political and addressed freedom and beauty- often the wives of the poets would memorize the words- keep them in their minds for decades until it was safe to reveal. I suppose I was feeling my own small entrapment and as a result wandered into an area of study based on a mix of home emotion. It was the double edged sword- there were days I didn’t think I would survive and yet it was such a complex and rich environment to be within. I am profoundly grateful for what they continue to teach me- even though the lessons can be a tough reflection on myself.

Linda Rossi: This is a wonderful opportunity to write about our adventures- as mothers and artists- I so appreciate these reflections. I have three sons who unfortunately due to crazy circumstances I had to raise from a young age on- by myself. My first son was born the day after my grad school exhibition. As I still had to finish the written part of my thesis- I was nursing and writing at the same time. I found it completely changed my interpretation of time and space- there was a blending and compression- I needed to accept quickly the chaos and the unexpected. As the years went on all 3 helped me make works of art- their skills and aesthetic knowledge grew and I was able to trust them (at a young age) for new insight into the work. It has continued to be a provocative and powerful exchange. During those years it was a matter of finding bits of time that I could create work,so a lot of the time I was dreaming about pieces -not actually making them- I would actually try to schedule time to make art in my head- for example while washing the dishes I would focus intensely on the work I would do in the future. At the same time one would find domestic and artistic tools side by side on the kitchen counter- the loaf of bread and peanut butter were spread out with saws, wood, etc. Probably not the most sanitary- but it was a way to not separate our lives. I look back now on years that were filled with pain, beauty, terror, humor,profound baby -teenage boy smells, and yelling and and fear and laughing and it still continues. The intensity of the home fueled the work I created. During a certain time period I created an elaborate installation about Russian poets whose voices were suppressed by Stalin. I became interested in the power of art during a time of danger- the strongest work was less political and addressed freedom and beauty- often the wives of the poets would memorize the words- keep them in their minds for decades until it was safe to reveal. I suppose I was feeling my own small entrapment and as a result wandered into an area of study based on a mix of home emotion. It was the double edged sword- there were days I didn’t think I would survive and yet it was such a complex and rich environment to be within. I am profoundly grateful for what they continue to teach me- even though the lessons can be a tough reflection on myself.

Carrie Thompson: Like Linda, I am raising my son (Goma) in a non-traditional home. I don’t need to get into details but the descriptive word I would use is complicated. And like Amy, I struggle with the amount of time that Goma spends in daycare. As you probably know, I am Alec Soth’s studio manager. My job is full-time and demanding. Since I work for an artist, most nights after Goma falls asleep the idea of working on my own art makes my head spin. My issue is that I, like many of you, need time to create, think, and explore. I can’t just turn my ideas on and off. I am 31. Goma is 15 months old. Before Goma was born I got my job with Alec, won a few grants, made two bodies of work that I am proud of, had many shows, traveled, and applied for every grant and show for which I was eligible. Now since I have a child I do less than half of these things. This is why I think younger artists without children rise to the top quicker. Artists with children continue to create yet not as quickly. As many of you have mentioned, the idea of success shifts when you become a mother. I would love to hear any other thoughts you might have on the discussion to this point, and I would like to add one more question: Since becoming a mother what is the one thing you gave up that you wish you had back?

Danielle Mericle: One quick observation, and then I will write more later. I too work a full-time job, although I’ve managed to get it down to four days/week instead of five (it does help). And while I don’t pursue many aspects of my work nearly like I used to, it’s definitely starting to come back, however slowly. My sense, and others chime in here, is that it gets easier all the time. The difference between 15 months and three (which is how old Charley is now) cannot be underestimated. I’m guessing that three to six will be another huge leap, and so on and so on. That said, the challenges are very real. I’m incredibly fortunate in that I convinced my mother to move to Ithaca to provide childcare for us (we pay her well, but still, my guilt is gone)- when I was sending him to daycare it was pretty agonizing… Anyway, more soon- and I will contemplate what I wish I had back (it’s finally happening, however, where I really can’t remember my old life much anymore-so I may have to ponder the question a while).

Beth Dow: Our kids were born in London, and I was pregnant shortly after my first solo exhibition. I continued to shoot film but it was difficult to work in the darkroom, and this became basically impossible after our son Miles was born. Our daughter Maisie was born less than two years later, and then we moved to the USA not long after that. The film I shot back then was roll after roll of unfinished thoughts, and it was deeply frustrating to not be able to print. I also didn’t have my own darkroom, so I had to use my husband’s when he wasn’t in it, which was only nights or weekends. I wanted to apply for grad school at that time, too, which then became impossible. I was still able to get my work in some group shows, but I didn’t regain any kind of real focus for several years. I don’t know how much the international move had to do with that, though, but that could have played a big part. My London gallery completely changed its business model and became a picture library at the same time we moved, so I also no longer had representation. Looking back, I don’t know if I would have really changed anything, but I do wish I had had more bodies of work under my belt before I grew a baby there (ha). When you asked what was the one thing I gave up that I wish I had back, I really had to think about that. Life is all about giving things up and getting things in return. Sometimes we get things we don’t want, and other times we get things we didn’t know we wanted. I wish I could regain the freedom to completely throw my full attention into one thing at a time, and to do that without any guilt. When I’m doing family stuff, whatever that may be, part of my mind is on my photographs; when I’m working, part of my mind is on who needs to be where, what’s for supper, and what is that goddamned dog barking about now. I suspect this is a gender thing, whether it’s the divided focus or the guilt about that division. I do know, however, that it gets easier. After a huge gap in my resume, things picked up for me as the kids went to school and became more autonomous. When the kids were small I would fantasize about what it must have been like for Ward Cleaver to return home to a clean house and a cooked dinner. There were also a few dangerous occasions, after long and stressful days with toddlers, where a full tank of gas, some loud music, and a bit of cash in my bag were calling out all kinds of temptations to just keep on driving. I bet a lot of mothers of young children have felt like that, and I’m suspicious of those who would deny it. I wish I could regain the facility to easily compartmentalize my attention, and I wish I could do so without feeling any shred of guilt.

Greta Pratt: I have raised two children in a traditional/nontraditional home. Traditional because I am married. Non-traditional because my husband and I live in different states eight hours apart. I have a tenure track job in Virginia and he needs to be close to New York City. It is complicated. I always knew I wanted to have children but I don’t think I gave a whole lot of thought to all the practical issues of having children. I proceeded as I do with most things by just winging it. Sometimes is has worked out better than others. When the kids were little I was home with them and my work time always involved towing them with me unless I could find a mom to trade a few hours of kid- watching with. I didn’t have the money to hire a sitter. My husband, who is a freelance editorial photographer, travels non-stop and without much advance warning, so he was not available for any kind of consistent help. I learned to shed things so I could continue to photograph and take care of my kids. No time for a social life, reading the paper or books, watching TV, keeping up with current events or talking to friends. I did however manage to keep my focus and keep working towards a goal, however slowly. At that time I was working on what would turn into my second book of photographs, “Using History” It took me eight years to finish the project. Part of the reason it took so long was figuring out and understanding what I was trying to say; another part was the travel involved; and another huge part was the figuring out how to fit in the kids. I did a lot of driving in those days. When Axel was eight and Rose was six I went back to school and got my MFA and that led to my current full time job. I do feel like my life went completely out of control from that point on. The demands of graduate school and then a job in academia along with creating art and raising my kids have been intense. Also, I moved to a different state and my husband stayed behind. What was I thinking? As I stated earlier, sometimes it has worked out better than others.

Paula McCartney: There’s a lot I miss, actually (at 37, I was very used to my adult life and the freedom I had when he was born), but NOTHING enough to trade back! I am certain that Oliver is the most amazing thing that has or ever will happen to me. I guess the thing that I miss the most is the ability to go out in the evenings. Lex and I used to always go to openings and lectures and I thought of that as my continuing education, as well as a way to stay connected in the community. Without family in town, we honestly can very rarely afford a sitter, so we hardly ever go out at night, which feels isolating at times. And going out to dinner together for a date and paying for a sitter is basically out of the question. I am lucky that Oliver goes to –and loves– preschool several days a week, so I do have studio time (I didn’t for his first year, and didn’t make much work) and realize that I make as much work now as I did on average before he was born. I love him more than anything, but my work is still very important to me. I will admit I do still worry about my career. But, I am able to NOT worry about it when I am spending time with him and can be really present; I just worry while driving to work or at night when I should be sleeping!

Greta Pratt: My kids are now 17 and 19 so it is hard to remember my life without them and what I gave up. But in thinking about it, what I would like to have back is time with my partner where the conversation is not related to the kids. I also miss the freedom to pursue an artistic idea without having to think about what a houseful of teenagers is doing back at home. It is tough to find balance and as Paula pointed out before it is impossible to be the best at everything all the time. There are just not enough hours in the day. When I was first getting started a male museum curator counseled me not to have kids. He said I would never be successful if I had them. I was incensed. But if you define success as a race to the top he was right. Nurturing children, making a living, and being an artist comprises three fulltime jobs and that is impossible. However, life is richer when we look at it from many angles. If we want a world comprised of diversity of thought and ideas maybe we need to understand that the old path to success does not work for all types of people and we need to seek out and value the contributions of a variety of individuals.

Amy Stein: Well, sleep would be up there on a list if things I sorely miss. Also, freedom to plan my own day and unstructured time are distant memories. Now every moment and activity’s value is weighed against spending time with Sam or the cost of hiring a sitter. So a lot of things I used love to do I just can’t make time for: going to openings, attending talks, waking in the park, showering. Sometimes I feel like every moment of my day is consumed by mothering duties, and to break free for even a minute I need to negotiate with someone to take over and spell me (having said that I have an attentive and loving part time sitter and my husband is amazing and shares many duties, especially in the evenings). Carrie thanks so much for initiating this conversation and pushing it forward. I’ve come to really look forward to reading everyone’s responses. Especially because the other moms are more experienced and have a broader perspective to share. Sometimes I loose sight of the fact that Sam will not always be 7 months old, with the intense needs of an infant. He will of course grow and go through many stages of development and increasingly become more independent and need new and different things from me.

Linda Rossi: In response to Amy’s mention of the need for sleep, it has been an enormous issue for me over the years as my boys were not good sleepers and then I waited up all night once they were teenagers. One evening I remember in particular was when my oldest son, Skye, who was two at the time would never stay in his bed; around midnight my husband and I pretended to be asleep ( while waiting for him to go to bed –he apparently was in charge). I remember him coming into our room and standing next to me. I could sense his closed fist holding a toy right above my face. He wanted me to read what it said on the bottom of the toy car. With great delight he said, “Oh, they are sleeping and they are dreaming about me!” As I was so sleep deprived, the concept that when I did get a wink I would be dreaming about him was both funny and excruciating. If I could change one thing it would actually be to get more sleep. I would encourage younger mothers to get as much rest as possible. I would often use the late evening hours to “make art” and as a result it has actually compromised my health. I now try to get more sleep and dream about new work when I go to bed, as the often random connections in a dream state lead to new ideas.

Carrie Thompson: Like Beth, I was thinking a lot about freedom when I wrote the question, “Since becoming a mother what is the one thing you gave up that you wish you had back?” I would love to have the freedom to really plunge into a project without guilt. I dream of taking off and exploring the world slowly and completely. I think this is a dream for many artists, not just women. I think there are probably a lot of women –and mothers– who share the escape fantasies of Lester B. Morrison, and one of Beth’s observations has stuck with me, and almost perfectly sums up my own conflicts: “I often feel like I should apologize to my kids for having a career, and to my career for having a life.”

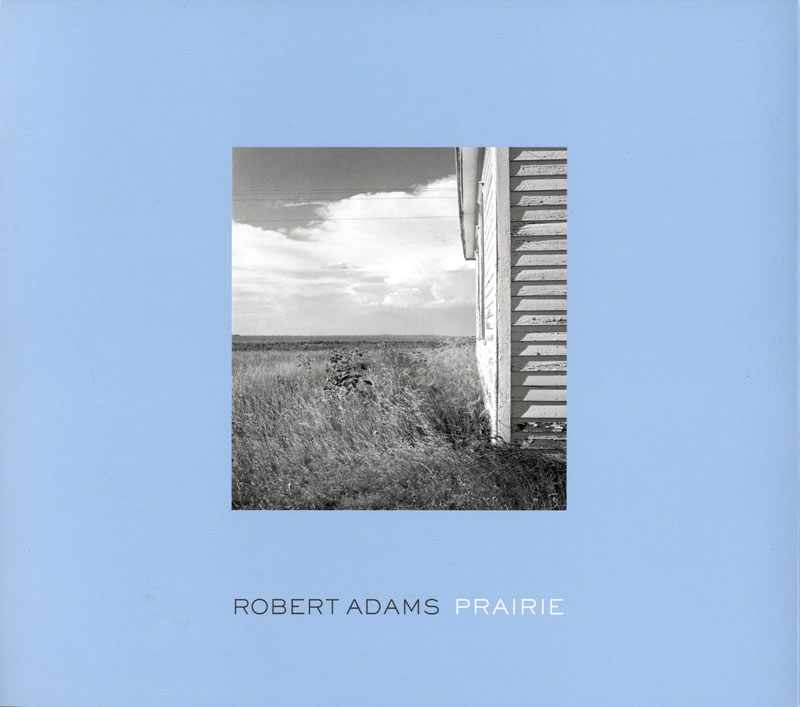

I often say that I understand Robert Adams a little bit more every year. Entering my 42ndyear , I guess I’ve been deepening this understanding for about 22 years. But I still keep learning. This year’s lesson came from the reprint of an Adam’s book from 1978: Prairie (2011, Denver Art Museum & Fraenkel Gallery).

I often say that I understand Robert Adams a little bit more every year. Entering my 42ndyear , I guess I’ve been deepening this understanding for about 22 years. But I still keep learning. This year’s lesson came from the reprint of an Adam’s book from 1978: Prairie (2011, Denver Art Museum & Fraenkel Gallery).